Silicon Valley in so many ways is the incendiary of the U.S. economy, keeping it cooking with vitality and innovation. It also may be sucking the entrepreneurial life out of the rest of the country.

Over the past few years, we've seen two apparent crosscurrents in the startup waters. One is the tech explosion in Silicon Valley, where it seems like even your great-aunt who still looks up numbers in the phone book could launch an app with a silly name and get $50 million in funding. The other trend is an overall decline in entrepreneurship across the U.S.—revealed by statistics and felt in places like Atlanta, Kansas City, Missouri, and smaller towns.

No one has proved a direct link between the two trends—it's possible there is no correlation, but, then again, a jury let O.J. off too. The case against Silicon Valley is compelling. We live in an increasingly winner-take-all society—a dynamic exacerbated by recent technologies such as cloud computing and social media. And when it comes to entrepreneurship, Silicon Valley is the clear winner, taking it all. New York does OK as the No. 2 (the Lyft to Silicon Valley's Uber; the Hunt's ketchup to the Valley's Heinz). Everywhere else gets the scraps.

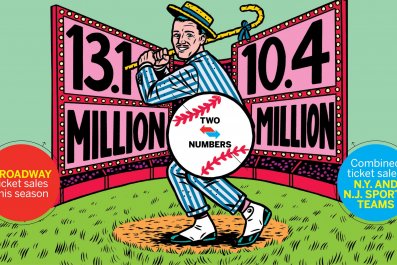

Almost any way you measure it, you'll find a vast startup gap between Silicon Valley and the rest of the country. Look at the money going into companies. Venture capital firms in 2014 pumped more than $32 billion into startups based in the stretch from San Francisco to San Jose, according to the National Venture Capital Association. That's twice as much as all of the venture capital put into companies in all of the rest of the U.S. New York and Boston are neck and neck at No. 2, at about $4 billion each. After that, the drop-off is steep.

Or look at the daily fundings from all over the world listed in newsletter StrictlyVC. On May 29, for instance, StrictlyVC reported that Wealthminder in Reston, Virginia, raised $1.5 million, CyberFlow Analytics in San Diego got $4 million and Twenga in London got $11 million—while Silicon Valley's Beepi, a two-year-old platform for selling used cars, got $300 million to add to the $80 million it already raised. Just being in Silicon Valley seems to get you 10 times more money.

At the same time, U.S. entrepreneurs have been starting about 25 percent fewer companies in the 2010s compared with the early 2000s, according to data from the Census Bureau. A 2014 report from the Brookings Institution said the decline in entrepreneurship "points to a U.S. economy that has steadily become less dynamic over time." Tech pundit and former IBM strategist Irving Wladawsky-Berger wrote: "Why is entrepreneurship on the decline when starting a company has never been easier? This is a truly surprising paradox."

The leaders of the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce recently convened to discuss this. Four years ago, they launched a program aimed at "becoming America's most entrepreneurial city"—which, as a goal, was already a stretch, like Kim Kardashian aiming to become America's next great neurosurgeon. Not a big surprise that the city ran into a wall: Entrepreneurs there had a hard time getting funded. "We've seen a number of companies leave the area because of a lack of capital formation here," said Terry Dunn, chairman of the city's chamber of commerce.

A simple link between these trends might go like this: There's only so much money to be invested into startups, so if more of it is going to Silicon Valley, less of it is available to go elsewhere.

But there's even a slight kink in that hose. In Silicon Valley, the number of companies being started is down from record levels of the dot-com boom years of 1995 to 2000.

Add it all up, and money that at one time might've been spread among lots of young companies across the country is now getting lasered into a handful of companies on one 50-mile strip of land. This helps explain the crazy-ass valuations we've been reading about—Uber worth $50 billion; Slack worth $3 billion. All the money is chasing the few presumed winners.

The blame goes to the tech universe we've created. More of life and business is becoming digital. Industries, like personal transportation, that never thought they were digital increasingly get disrupted by digital newcomers, like Uber and Lyft. Once a business is digital and in the cloud, one company can quickly take over the whole sector. You create a product or service on an app in the cloud, and it instantly is available to the world. (Very different from physical businesses, like making a refrigerator or opening a restaurant. Those take time and far more resources.) If it takes hold and gets a pile of funding to secure its dominant position, potential competitors anywhere else quickly get frozen out.

Venture capitalists have told me that smart investors know this, and they don't want to invest in a me-too startup that will have little chance of making a big splash. That's why a lot of entrepreneurs find they don't even get a chance to get started.

Another recent trend is no doubt contributing to this problem. Companies are raising bigger private rounds of funding and putting off going public. That means fewer private investors are deciding where the money goes instead of a broad public base of investors, and a whole lot of those private investors are sitting in Silicon Valley offices.

A growing number of smart people think this situation is not a good thing. The success of Silicon Valley isn't firing up other regions—the flow seems to be going the other way, from the rest of the country to Silicon Valley. It's not Silicon Valley's fault. This is the outcome of the technology we've set up. We already know that a lot of money is getting concentrated in fewer hands—that whole 1 percent thing. Now it's also going into fewer geographic places. And absent entrepreneurship, the places left out have little chance of renewing themselves for the modern era.

Steve Case, founder of AOL, is so concerned by this that he is traveling the country by bus, holding startup contests in cities like Atlanta and Richmond, Virginia. "We've found some great entrepreneurs with a lot of ideas who are not getting capital," Case tells me. He's trying to help give them a jump-start, but it might be a quixotic cause.

Just tell your great-aunt that if she can't fund her app in Albuquerque, she should move to Palo Alto. She could be cruising down the 101 in a Maserati in no time.