You can tell an unsettlingly comprehensive and riveting history of New York City through the murder of its single white women: Elma Sands, strangled and thrown down a SoHo well in 1799; Helen Jewett, a prostitute killed with a hatchet and then lit on fire in 1836; Alice Augusta Bowlsby, discovered in a suitcase in 1871, killed by an abortionist, in what came to be known as the Great Trunk Mystery; the so-called Career Girls, Emily Hoffert and Janice Wylie (who worked at Newsweek), murdered in their Upper East Side apartment in 1963; Kitty Genovese, stabbed to death in 1964 outside her house in Queens, as neighbors listened to her cries; Kendra Webdale, pushed in front of a subway train by a schizophrenic in 1999; Sarah Fox, killed in 2004 while jogging through a park in the gentrifying upper reaches of Manhattan, possibly by a deranged Russian.

The history of the Western world is sometimes subjected to a Great Man narrative: Plato, Caesar, Kant, et al. There have been great men in New York too, but their greatness is almost inevitably supplanted or forgotten. The dead women linger. Though silent, they still speak.

No case says more about what New York once was and has now become than the murder of Roseann Quinn. She was alone in the city, trying to build a life. She had some resources and some ambitions. She was average, but not ordinary. Then came the night of January 2, 1973—an encounter in a basement bar, a walk across 72nd Street, the lights of her native New Jersey burning in the distance like the bonfires of an enemy encampment. A few minutes later, she was dead. She was only 28.

Her killer, found quickly enough, committed suicide in jail. Justice was thus served, crudely but effectively.

And yet Roseann Quinn did not withdraw into oblivion. She remains with us, stalking the streets of a city that likes to think of itself as supremely welcoming and safe, a city that wants to prove, more than any other in the world, that millions of people can subsume their animal yearnings and anxieties as they daily board crowded trains and wait in line for cronuts, reaffirming with each "excuse me" the tenets of Western civilization.

Not so, whispers Roseann Quinn.

I knew it was time to leave New York when I was paying as much for a monthly parking space in brownstone Brooklyn as I did for my first apartment, on a strip of Williamsburg where, 15 years ago, old Poles still glowered from storefronts and the hipsters skipping down Bedford Avenue were proud to live in a neighborhood whose primary financial institution was a sclerotic ATM at a corner store. Today, Williamsburg is about as culturally transgressive as the Mall of America. I leave with no bitterness, but it is time to go.

My impending departure put me in mind of Roseann Quinn, or rather the oddly enduring Looking for Mr. Goodbar franchise, to which her 1973 death gave rise. The 1975 novel by Judith Rossner, which turned 40 this spring, was, at the time, ecstatically reviewed, with The New York Times comparing Rossner's main character to the female protagonists of Henry James and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Newsweek called the book a "hard, fast, frightening read." Two years later came the film version, starring Diane Keaton and Richard Gere, which is most notable for Keaton's nude scenes. Quinn (Theresa Dunn in the book) thus entered that unlucky pantheon of women who have come to serve as history's unwilling lessons.

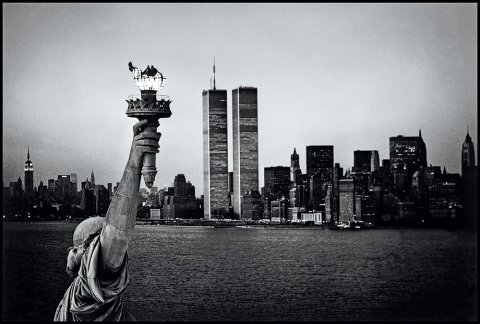

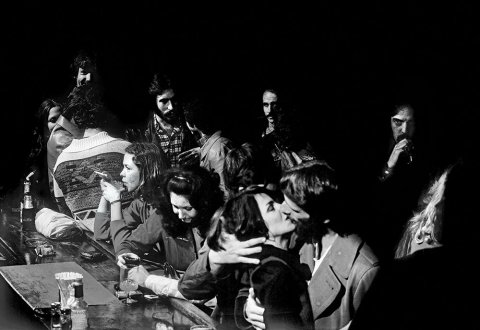

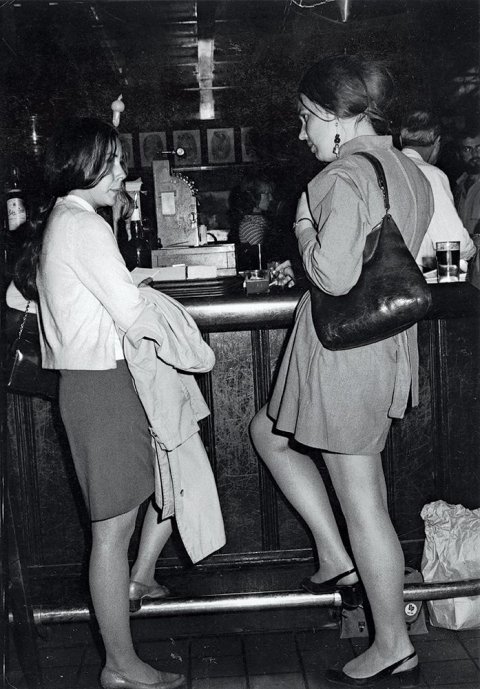

All history, in the end, is just a romance with bygone time. My own romance was with a time and place more frequently scorned than loved: the city of riots, strikes and blackouts, of dusky bars where Roseann Quinn spent her evening hours, some nights craving solitude, other nights craving company. The city back then, as I saw it, was more dangerous and more compelling. It was Gotham fallen, brooding and bruised, a city for Roseann Quinn, not Carrie Bradshaw. If you could make it there, why would you want to make it anywhere else?

Unable to travel back in time, I resorted to more mundane means. I happened to then be working at a large cultural institution uptown, where one of my colleagues was a woman in her late 30s. We both looked with condescension at our colleagues, most of whom very much wanted to ape the lifestyle of Friends, Sex and the City or Seinfeld, if not some lavish combination of all three. So it was only natural that we spent an increasing amount of time together: Nothing unites people like shared enmity.

She had come to New York in the grimy mid-'80s, just as crack was invading Harlem and AIDS was invading Chelsea, while a resurgent Wall Street seduced young men for whom Gordon Gekko would become an unironic ideal. She would take me on long walks through Manhattan and point to where the legendary clubs had once stood: Here was Limelight; there was Danceteria. Now, it was all a CVS. Her life, in that New York of broken windows before Broken Windows, seemed infinitely richer than my own, in Mayor Bloomberg's global metropolis, where smoking had, preposterously, just been outlawed in places where we could keep guzzling alcohol and tearing at chunks of red meat.

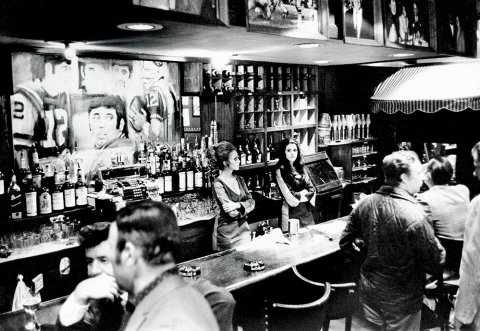

Speaking of bars, we often ended up at a pub called the All State Café. It was an oddly ecumenical name for a basement watering hole on 72nd Street, on a strip where there had once been many "singles bars." These were mostly gone, replaced by establishments for those who had shed their solitude for familial arrangements. Down the block was a kosher barbecue restaurant that catered to the neighborhood's large population of faithful Jews, who had arrived as the Upper West Side returned to prosperity in the late 1990s. It wasn't a very good restaurant, but it was always very full. Such are the vagaries, I guess, of barbecue for the Orthodox.

The All State was the kind of place where the music was quiet and the voices low, almost reverentially so. The place was tidy, but not gleaming in the fashion of today's bars, which seem to eternally await a health inspector's arrival. My co-worker said Kevin Bacon had once tended bar there, which seemed plausible but not all that impressive. Then she told me Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the book and film about a woman murdered during a one-night stand, was based on a fatal encounter that took place within these confines of dark wood stained with grease and cigarette smoke (the place had been called W.M. Tweeds at the time). This was infinitely more intriguing.

That was the first I'd heard of Goodbar. The seed lodged in my brain and, over the ensuing years, grew with mulish persistence, pushing through all the inanities that accrue in the course of a normal existence: Is that Korean place still on...did she leave Goldman Sachs for…? Once in a while, its roots would hit some major neural tangle and I'd fall into a reverie about Roseann Quinn, hunched over book and scotch at the All State Café. Goodbar became, to me, a strange cousin who lived on Staten Island, who showed up rarely and unpredictably, but always with a wild story about Norman Mailer or RuPaul, about some goons from Queens who once beat up Dee Dee Ramone. Goodbar rebukes the international city where Bowery bums are now more rare than Russian billionaires, reminding us of what lies beneath the layers of varnish, at once thick and ephemeral. Its lessons transcend changing demographics, real estate prices, crime trends, even the world-acclaimed sophistication of brownstone Brooklyn. They whisper of something darker in the human condition, something as relevant in 2015 as it was in 1973 or 1799.

I am reminded of a photograph by Steven Siegel, who gloriously captured the city in some of its least glorious days. It shows the facade of the Times Square Theater in 1996. Nothing is playing inside, but the marquee is one of several in the neighborhood that bears a message from the artist Jenny Holzer. This is what it says: "Murder Has Its Sexual Side."

Roseann Quinn was—and is—the classic good girl gone bad, which is probably why Goodbar endures. It was recently even turned into a rock opera by some enterprising young Andrew Lloyd Webber postulant. In the past year alone, it has been mentioned by The Paris Review and the liberal political blog Daily Kos, as well as the Gawker spin-off blog i09. Everyone loves a little blood, as long as it is not their own.

"An illustrated lecture on how nice girls go wrong," Pauline Kael called the film version of Rossner's book. Good Girl Gone Bad was the name of the 2007 record by the R&B singer Rihanna, who was famously beaten in 2009 by her boyfriend Chris Brown. The terrible subtext is always the same: The girl is a victim, she didn't deserve it, except didn't she, kind of, just a little bit? It was true with Rihanna. It was true with Quinn.

In Rossner's telling, she is not quite from the hinterlands, but her section of the Bronx is so Irish, she might as well be from County Cork (the real Quinn was from the New Jersey suburbs, as you would learn from Lacey Fosburgh's Closing Time, billed as "the true story of the Goodbar murder"). Her escape to Manhattan, in part, is an escape from the fate of a sister who has become just another "Catholic baby-making machine." Today, many come to New York for something: It's too expensive to live here unless you have a very good reason to do so. But back then, when everyone seemed to be escaping the city, you could effectively homestead in Manhattan as pioneers once did on the Great Plains. The rats back then were the size of buffalo. Or so I hear.

Not that the fictionalized Quinn whom Rossner depicts in Goodbar is an aimless romantic, wandering Greenwich Village in search of Joe Gould, writing poetry in a cold-water flat. She's not far enough removed from the old sod for that kind of blissful impracticality. She goes to City College, where she has an affair with an English professor who seems to treat his charges with undiluted contempt. His intensity attracts her: "His eyes bored a hole in her and the hole was her whole self." Putting aside the ontological problem of "the hole was her whole self," you get a pretty good idea of Rossner's hard-boiled prose. If not, here's another shot, from a later tryst: "She came, understood that was what had happened to her but not what was important about it." This isn't great writing, but it is great style, Hemingway filtered through second-wave feminism and hyperintellectual Jewish New York straining to get out of its own head.

If anything, Rossner is too hard-boiled, too willing to open the curtains of Quinn's studio, letting her readers watch her procession of sexual escapades. While Fosburgh's nonfiction account gives proper due to Quinn's teaching career at St. Joseph's School for the Deaf and elsewhere, Rossner spends far more time in bed than before the blackboard. She describes a sex life that is rich and then, suddenly, a little too rich for our bourgeois sensibilities. Her Quinn begins to frequent the city's bar scene, apparently using sex to fill some vague inner lack. "She's in here plenty," one bar denizen says of her. "She fucks anything in pants." Later, she begins to date a lawyer named James, but he is too timid for her. "I've slept with men I hardly knew," she says to him, taunting. Rossner, ever the goading devil, has her think: "If you could give me a good beating when I acted like that, I would like you better for it. I might even be able to enjoy the sex." Well, at least she knows what she likes.

"A Manhattan singles spot," Mr. Goodbar makes its appearance about halfway through the novel as "a comfortable place with old gum-ball machines for table lamps and one wall covered entirely with a shellacked montage of candy wrappers." I don't remember a Snickers mural at the All State, nor any gum-ball machines. But it was a comfortable place, lacking light but not warmth.

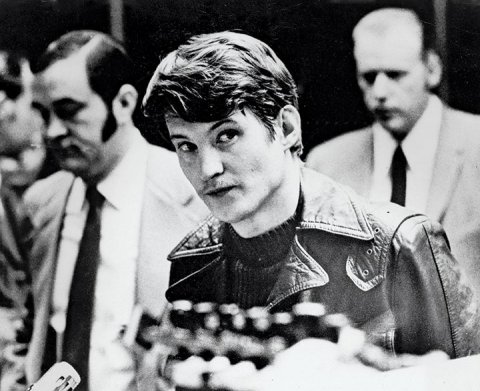

Goodbar is where the fictionalized Quinn meets Gary Cooper White, Rossner's name for the real killer, John Wayne Wilson. White is a drifter of indeterminate sexual tastes and obvious mental instability. She takes him back to her place anyway, so hungry is she for the rough stuff. In her squalid apartment, they copulate as gracefully as teens on prom night drunk on Franzia and pheromones. She doesn't think he is very good at it, though, and kicks him out. Enraged, White stabs her to death.

The book opens with his confession. "Boy, some of the people they got teaching kids, I'm keeping mine out of school," he tells the police. "Especially if it's a girl."

The tabloids of New York exist mainly to affirm the ancient truth that we are bastards all. They seize on human failings—crime, corruption, betrayal, greed—with an irresistible position that is half outrage and half glee. Their columnists can, in a single paragraph, play priest, bartender and undertaker. Sometimes they can do it in a single sentence.

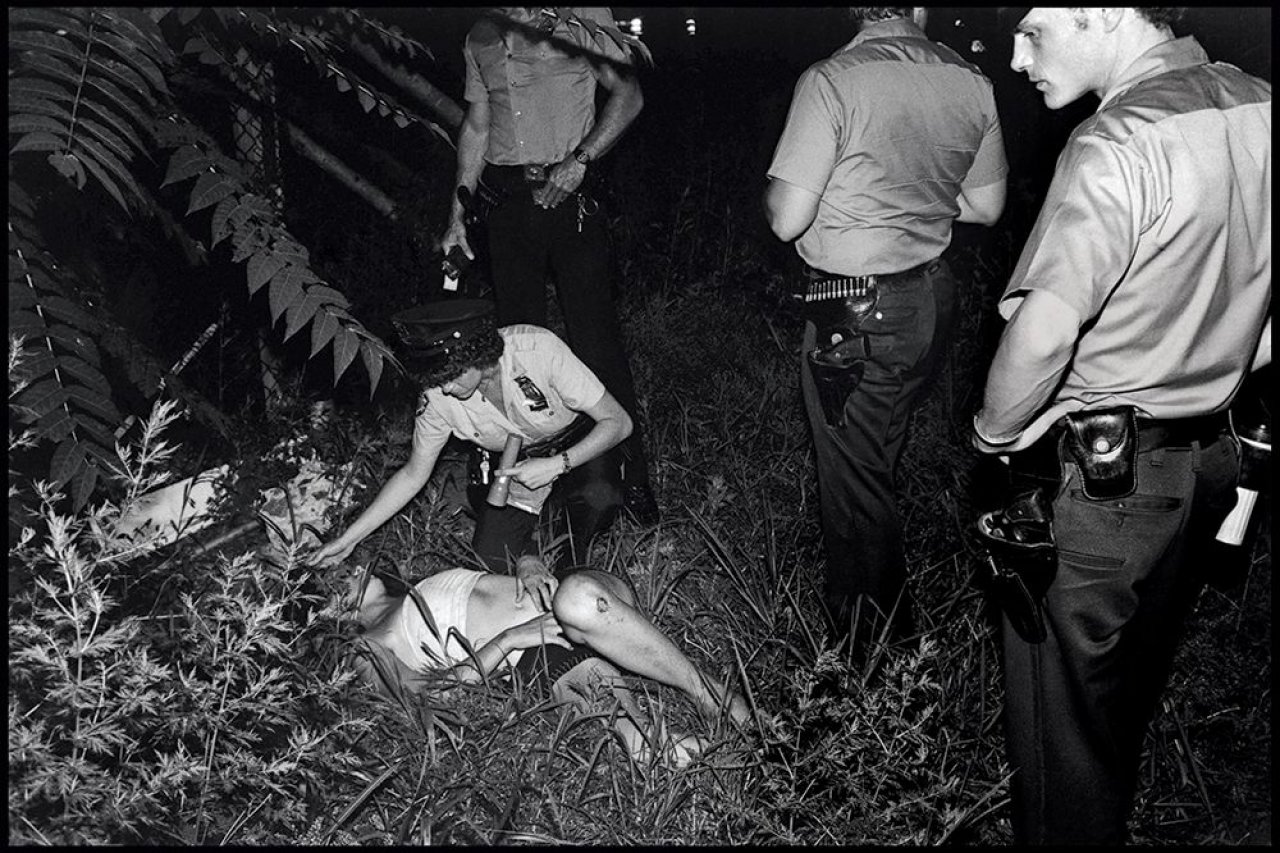

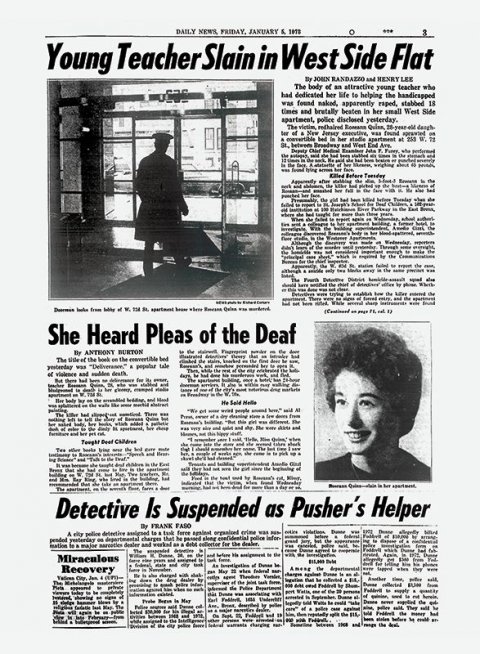

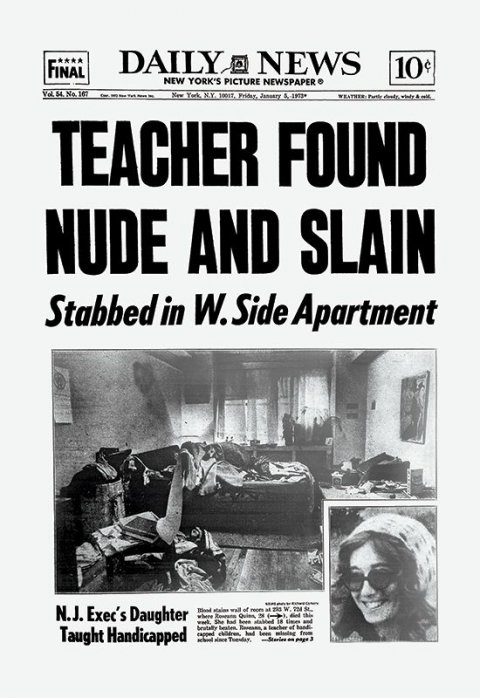

Quinn's body, which Wilson desecrated with 18 knife wounds, was found by the superintendent of her building, where a fellow teacher from St. Joseph's went after she failed to show up for her classes. It took several days for the New York Police Department to announce the discovery of Quinn's body, but once the news hit, it stuck. "Teacher Found Nude and Slain," blares the wood (the front page headline, in tabloidese) of the Daily News on January 5, 1973, showing both her squalid apartment and a headshot of Quinn, in sunglasses, smiling. "Young Teacher Slain in West Side Flat," says a headline inside the paper. "She Heard Pleas of the Deaf," declares another, about her teaching career.

Sometime later, the feminist Susan Brownmiller wrote about the way the case was covered in the tabloids, surmising that "the subliminal purpose of the tabloid rape-murder headline is to provide male readers with enough stimulation for fantasy." Brownmiller, who wrote a classic 1975 book about rape, Against Our Will, also notes that "women who die violently in New York City and who fall into the category of young, white and beautiful are memorialized in tabloid headlines and story copy that attests to their physical appeal to men, whether or not their physical appeal was actually related to the crime."

This is a fair critique, and no less fair in the four decades since Brownmiller made it. The mere perusal of the morning paper often leaves me horrified, at once afraid for my daughter and ashamed of all those who carry the Y chromosome. Men are the carriers of the virulent darkness that claimed Elma Sands in 1799 and Roseann Quinn in 1973. Just this afternoon, a few hours before I sat down to write this, the NYPD arrested a middle-aged man named Rodney Stover. The previous Saturday, at about 7:45 p.m., a woman who had been drinking with her friends at the Turnmill Bar on the East Side of Manhattan went downstairs to use the bathroom. Stover, who lived in a homeless shelter nearby, jumped out of a stall and raped her. Nobody heard the woman's cries.

There are stories like this every week. Some are worse, some are not quite as horrific. When I was at the Daily News, one of my colleagues on the paper's editorial board was Errol Louis, now the host of a political talk show. In his column, he wrote with some frequency about the case of Chanel Petro-Nixon, a 16-year-old from Brooklyn who in 2006 was strangled and dumped in a garbage bag. She may have been on her way to a rendezvous with a man who turned out to be a rapist, but the case remains unsolved to this day. That means it will probably remain unsolved forever.

About four months before Petro-Nixon's death, a young woman named Imette St. Guillen was abducted by a bouncer from a lower Manhattan nightclub; he raped and killed her before depositing her on a desolate stretch of Brooklyn freeway. And about a month after Petro-Nixon's death, a woman named Jennifer Moore was abducted from a Chelsea nightclub. She was found later found dead, in a Dumpster, in New Jersey.

It fell to the tabloids, as always, to reach into the city's psyche and excavate the fears most of us would rather keep in the pre-linguistic, reptilian reaches of the human mind. The New York Post did not disappoint. It rarely does. The headline from July 29, 2006: "IT'S OPEN SEASON ON YOUNG GALS."

It has been suggested that Goodbar endures because it feeds our ongoing moral panic over women and their sexuality, that Rossner was engaged in the beloved activity of slut-shaming, as popular then as it was in the time of Nathaniel Hawthorne and as it is today.

"The reason Roseann Quinn's death terrified people wasn't that she was a freak or a hippie," wrote Sady Doyle in a Slate assessment of the film a couple of years back. "It was that she was steadily employed, modestly dressed, well-liked. She was normal. But she was a new normal—one that, decades later, we're still trying to deny or scare away." The new normal to which I'm fairly certain Doyle is alluding is the one ushered in a decade before Quinn's death by Helen Gurley Brown's Sex and the Single Girl, which told women that it was permissible to enjoy sex, to enjoy it often and to enjoy it outside marriage.

Doyle's argument has much merit, but it doesn't quite plumb the lightless depths of Goodbar. For me, at least, Goodbar is as much about men as it is about women. For while its portrayal of women is uncomfortable, its portrayal of men is unbearable. Are men naturally violent? It's impossible to say, since natural and violence are not concepts that easily lend themselves to quantification in a laboratory. But just open the newspaper: women stoned to death in Pakistan, sorority sisters raped at state schools and Ivies alike, wives beaten by lowlifes and highfliers. Even the marginally permissible cultures of revenge porn and pickup "artistry" revel in a violent predator-prey dichotomy. It was, in other words, not a mere lone psychopath whom Roseann Quinn encountered on that January night.

It is curious, by the way, that by the bedside of Roseann Quinn was found a copy of Deliverance, the 1970 novel by James Dickey. There are no women in the book, which is about a canoe trip four men take through the rural South. The most famous scene in the film version is when one of the group, Bobby, is raped by a hostile redneck who tells him to "squeal like a pig" (the scene is rendered differently in the book). Deliverance is about the violence in the heart of all men; when Dickey writes of the "unbelievable violence and brutality" of the river, I fear he gives moving water a bad name. All it does is flow, following the dictates of gravity and surface tension. It is we men who color that river with blood.

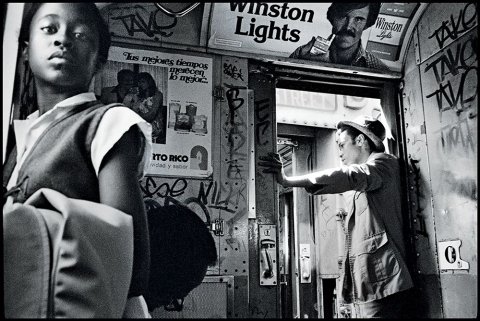

A few months ago, New York City still ashen with late winter, I took the train up to the Bronx. I don't know which train Roseann Quinn took to reach St. Joseph's School for the Deaf, so I had to guess and went with the 6. The train becomes elevated in the Bronx, but the view above ground is hardly better than the one below, a sea exhausted brick, the lower-middle-class neighborhoods close to the train besieged on all sides by housing projects with names that are either preposterously bucolic (Bronx River) or wildly aspirational (Sonia Sotomayor; John Adams).

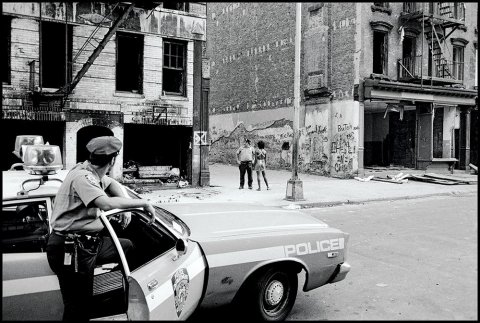

The Bronx is the only one of the five boroughs attached to the American mainland, and that has somehow made it an outcast in this city of islands. The borough is always on the cusp of resurgence, a favorite trope of the city's journalistic corps. And yet the former estate of Jonas Bronck (hence the name) has not, in the popular imagination, entirely recovered from that night in 1977 when, in the midst of a Yankees game against the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series, Howard Cosell famously declared, "There it is, ladies and gentlemen. The Bronx is burning." By the end of the decade, arson and poverty and drugs had reduced the Bronx to a pile of rubble that served as shorthand for all the ills of urban life. It has recovered, though perhaps not fully, and not everywhere. It will take more than a couple of loft conversions to undo the damage of generations.

St. Joseph's is in a remote neighborhood in the eastern Bronx called Throggs Neck, nestled on a grimy little lot right up against a highway named for Anne Hutchinson, who in 1638 was expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and in 1643 killed by Indians in what is today the northern Bronx. If you have ever driven north out of New York City, you have almost certainly passed by the school's blood-red brick facade, which appears to have ceded much of its original color to the permanent effluvium of soot. It would have been a long walk from the subway for Quinn, so she probably took the bus, which would have allowed her a few more minutes of Deliverance, as there was so little worth seeing outside the window.

The building is institutional Victorian, imposing and self-important, suggesting asylum more than school. There is religious imagery everywhere, but piety doesn't come easy under an expressway. At the front desk, the secretary was willing to let me look around, disconcertingly incurious about my unannounced appearance. I was searching for a memorial to Roseann, for some marker of her having passed through these doors. But there was nothing, or at least nothing visible. She was forgotten here, where she deserved most to be remembered.

I also went back to the All State Café, for the first time in a decade. It is now called the Emerald Inn. Curiously, the Emerald Inn was once located on 69th Street and Columbus Avenue. In the 1990s, a teacher named Jonathan Levin lived in the same building, in a third-floor apartment. Levin was killed in the spring of 1997 by one of his Bronx students when that student discovered that Levin's father, Gerald, was the chief executive of Time Warner. That, in many ways, became the defining murder of the late 1990s, a symbol as trenchant as Goodbar had been two decades before.

The Emerald Inn was fine. The food wasn't very good, but that may be because my tastes at 35 are slightly more refined than they were at 23. The beer was better than it had been, but it wasn't the good artisanal stuff, rich and funky, that you can reasonably expect at any halfway decent Brooklyn bar these days. The place was a little too bright, a little too clean. There was nothing sinister about it. And there should always be something sinister about a basement bar.

Next to me sat two men in suits, Masters of the Universe in training. I heard snippets of their conversation: complaints about nannies, private schools, the usual uptown preoccupations. Then the men paid for their beers and left. I watched the television above the bar against my own will, finding myself caring about a college basketball game I did not care about. It would be hard to read here, or to sit in the kind of fecund silence that Roseann Quinn frequently sought.

Then a woman sat down next to me. She ordered a drink and proceeded to sip it in a way that suggested she wasn't waiting for anyone. It dawned on me how rare it was, in 2015, to see a woman alone in a bar, sitting by herself, snug in her solitude, looking for no one, asking for nothing. I couldn't see her face, though it didn't matter. It could only be Roseann.