In late June, a short-haired, 41-year-old Russian in a black shirt and brown jacket entered a courtroom in Bonn, Germany. His face and appearance were completely unremarkable, yet numerous reporters, most of them Russian, were there, eager to finally see Sergei Maksimov, the man who allegedly had been terrorizing the Russian blogosphere for years—possibly at the behest of the Kremlin.

The prosecution contends that Maksimov is Hacker Hell, a cybercriminal who, since the late 2000s, has been breaking into email and LiveJournal accounts of prominent Russian bloggers and opposition activists. After getting access to a blog, Hell would usually delete all of its contents and write posts in deliberately faulty Russian, full of obscene language and anti-Semitic and homophobic remarks. He also maintained a personal blog, called "Virtual Inquisition," where he celebrated his achievements.

Since the government controls almost all the traditional media that matter in the country, the Internet has become the last area where real public debate can happen in Russia. It's also become a battlefield, where hacks, data theft and other forms of cyberwarfare are used to expose, compromise and hurt enemies, both in the opposition and the government itself. Whether Hell was a pawn of the government or not, the case offers a rare glimpse inside the shadowy war between Russia's internal hackers.

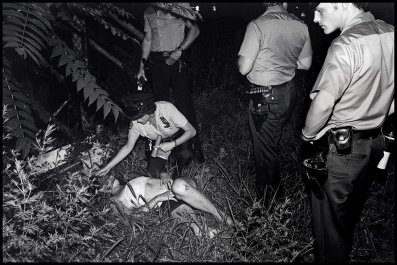

Hell made a lot of enemies over the years. He hacked popular bloggers and politicians, publicists and writers, and twice hacked the email and Twitter accounts of Alexei Navalny, a Russian opposition leader. Eventually, his enemies caught up with him. Two journalists who had been targeted by Hell took it upon themselves to find out who he was (and to publish their results in a blog, starting in 2010). Having pieced together various hints that Hell left in his posts (his degree from a Moscow university, his German residence, a physical altercation with another blogger that happened before his crusade started), they came to the conclusion that Hell was Maksimov, a Russian who moved to Germany in 1997. In 2012, Navalny hired a German lawyer who persuaded the local police to investigate Maksimov.

To do that, Navalny's team had to provide evidence and, among other things, translate Hell's posts into German. According to online newspaper Meduza's account of the court case in Bonn, when police came to Maksimov's house with a search warrant at the end of 2013, they found a notebook signed with the name "Hell" and a document called "Gospel According to Hell." After inspecting his hard drive, they discovered thousands of emails written by Navalny and his wife. They also discovered that Maksimov had access to an email address that used the name Hell. The secret question to restore the password on this email account was "What's my name?" The answer was "Maksimov," according to a police agent's testimony in court.

Maksimov is charged with counterfeiting, harassment and data theft. The maximum sentence he could receive is three years in prison.

Hell's targets were mostly opposition bloggers and liberal politicians, which is why some think he was a tool of Russian President Vladimir Putin. When he broke into Navalny's email and Twitter account for the second time, in June 2012, the hack came days after the politician's laptop and mobile phone were confiscated by law enforcement officers during a search. Some of the facts mentioned in the emails published by Hell were later raised in lawsuits that Russian law enforcement brought against Navalny. Hell gave several interviews to pro-government publications, stating that he had acted on his own and wanted to prove that Navalny was "a fraud."

No one has offered proof that Hell was working for the government, but such speculation is in line with a Newsweek investigation of Russian hackers and a recent New York Times report that said the Russian government keeps "factories" of Internet trolls on the payroll. "The Russian state is endlessly building itself up, and it strengthens not its schools and hospitals but the institutions that fight the enemies they made up themselves," says Anton Nossik, a Russian Internet pioneer and one of the top industry experts. He says the Federal Security Service or FSB, the main successor to the KGB, is known for using the tools of cybercrime to attack the opposition. "One of their methods is just to pass the stuff that they obtained themselves to a dummy who then claims that he got it by hacking someone." Nossik thinks that Hell was one such dummy and did most of his hacks with information he received from the government.

The Kremlin may have its pawns, but some hackers are fighting back. For the past 18 months, a vigilante hacker group has been steadily leaking information from the phones and email accounts of high-ranking Russian government officials. In August 2014, the group even hacked the Twitter account of Dmitry Medvedev, the Russian prime minister, and took control of it for 50 minutes, posting tweets such as "I resign. I'm ashamed of the government's actions. I'm very sorry" and "Something I have wanted to say for a long time: Vova [Vladimir Putin, Russia's president], you're wrong."

The group calls itself Anonimnyi Internatsional (Anonymous International), but it's usually referred to as Shaltai Boltai (the Russian translation of Humpty Dumpty). This is what the name on the group's contact email says, and even though the activists maintain it's just an alias for one of its members, the name has stuck.

According to a group representative who prefers to be called "Lewis" and agreed to answer Newsweek's questions via email, members of Anonymous International decided to use the names of characters in Lewis Carroll's stories, because "the world of Through the Looking Glass seems appropriate to describe the current Russian reality."

"There's so much absurdity and incompetence that even Carroll with all his imagination wouldn't be able to describe it," Lewis says.

Nossik, the Internet expert, backs that up. "The people who provide the technology for the government are fantastically incompetent," he says, adding while some organs of government are adept at cyberwar, others are not. For example, he says, 12 people are in charge of handling Medvedev's social media accounts, and each one of them knows all the passwords, so "if somebody gets drunk at a party and leaves his laptop open, everyone at the party can get access."

Anonymous International, which does not appear to be linked to the well-known hacker collective known as Anonymous, first came to prominence on December 31, 2014, when it published Putin's New Year's address to the nation several hours before it was broadcast. Since then, the group has been responsible for hacking Medvedev's Twitter account and releasing the alleged correspondence of various Russian officials, from a deputy prime minister to the head of Roskomnadzor, the government organization overseeing the media. From the emails attributed to the officials and their subordinates, it could be inferred that they put pressure on the media over how to spin certain stories, closely followed every step of opposition leaders and spent hundreds of man-hours monitoring jokes about the government on Twitter. Some people whose correspondence was leaked confirmed that the emails were real; the officials themselves did not comment.

Lewis says Anonymous International is an independent "team of people united by common purposes, one of which is to change the reality." In some previous interviews, he has said members of the group finance their operations from their personal funds; in others, he has said that undisclosed clients pay Anonymous International for information. "Both these statements are true," he told Newsweek. "And not all our clients know that we are Anonymous International. Far from all."

Lewis says things his team does for money may also have a real impact. "We would be happy if investigations were launched after our publications," he said. "But nothing has happened so far. We hope that this time eventually comes, but probably not very soon and after some big bloodshed. And some stuff we just leak for fun."

The access Anonymous International appears to enjoy has led some to suggest it might be backed by somebody within the government using leaks for leverage in internal power struggles or for PR purposes. Oleg Kashin, a prominent Russian journalist, says he came to that conclusion after noticing how "filtered" the leaked correspondence of one administration official was. "He turns out to be a kind of positive character: He doesn't steal, he doesn't orchestrate crimes, he's just a PR guy who does his job well," Kashin told Newsweek. "I really think this is just a new way of spreading the word about the work of the Putin administration for people who don't trust Russian TV."

Lewis dismisses that theory. "We have obtained all the documents and information ourselves, but if somebody thinks that we work for the Kremlin, we don't really care," he says.

He also says he believes Maksimov was only one of the hackers who used the alias Hell. "There were others. He's just the one who showed it off, and now he took all the heat. He is a simple cracker who used all the standard methods to hack simple email accounts."

In Bonn, Maksimov told the judge he wasn't responsible for the hacks and had just used the nickname "Hell" on several message boards. He also claimed that the real Hell helped him prepare for the trial, and that the reason he had Navalny's correspondence on his computer was because he was doing research for the case.

Anonymous International, according to Lewis, is following the trial with "pity...this guy was just used and thrown out, like a condom." As for the group members, they are aware that they could be arrested and prosecuted too, but "if it happens, it happens."

"At least, unlike Hell, we won't be ashamed of what we did."