The worst of Katrina was an act of man, not an act of God.

I heard something like that from every local I encountered in New Orleans earlier this year. No matter their age, race or religion, the people of this city pretty much agree that referring to Hurricane Katrina as a natural disaster is naive, even ridiculous. They all know it was a three-part storm. First, a Category 3 hurricane, then a massive failure of the levee and then the biggest disaster of all: the government's involvement.

Longtime residents of New Orleans were used to grappling with nature, but man was a harsher beast. Over 1,800 people across five states died as a result of the crisis in 2005, many because they were stuck in their homes. Thousands more suffered for days inside the Superdome before help arrived. The devastation that came after the storm was man-made: a combination of racism, opportunism, corruption and ignorance that has impaired the quality of life in this city for the past 10 years.

In the months following Katrina, New Orleans became a battleground for vested business and political interests fighting for how they wanted the city rebuilt. Some saw a political opportunity, flying in from Baton Rouge and Washington, D.C. Some simply crossed over from the suburbs or nearby university campuses to declare their plans for the city to anyone in then-Mayor Ray Nagin's office who would listen.

In the midst of the lobbying, map redrawing and back-door meetings, few people bothered to ask New Orleanians how they would like to see their city rebuilt. It was—though soggy, busted up and run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)—still their home, after all. It was their interests, their houses, their lives that needed rebuilding. But instead of transparency and aid, they got bureaucracy and ignorance.

Charity Versus Profits

On August 26, 2005, the Friday before Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, three days before the levees broke, Dr. Brobson Lutz, a longtime New Orleans resident, headed down to Galatoire's in the French Quarter for lunch. He decided, based on advice from waiters at the restaurant, that he and his partner would wait out the storm at their French Quarter home, since the area was on higher ground than much of the city. With the exception of a door flying open, they had no problems from the storm, but once the blowing stopped, Lutz was suddenly on a 24/7 treadmill, the French Quarter's resident doctor for weeks.

Lutz was uniquely suited to be a Katrina doctor. He'd completed his residency at Charity Hospital in the 1970s, a public hospital known for its trauma unit and willingness to care for New Orleans's large uninsured population. "We treated everything from heart attacks to pneumonia to fainting in church," he recalls.

In those hectic days following the storm, Lutz paired up with an emergency medical team from California. "We treated people in the streets for six or eight weeks," he says. This makeshift clinic was one of many, though Lutz's was among the more accessible in the area: FEMA lodged its clinic "in the bowels of the Omni hotel," a ritzy establishment that required everyone to go through two layers of security.

After Katrina, New Orleans hospitals had to deal with damage and outages, and improvised clinics popped up around town: in trailers, abandoned department stores and, in some cases, large tents. The mentally ill no longer had regular access to psychotropic medicines or even beds. To obtain prescriptions, Lutz and his crew relied on a psychiatry doctoral resident familiar with Charity Hospital and a police officer they called "the pharmacist," because he was adept at commandeering supplies they needed from drugstores.

That resident was the first to give Lutz the disturbing news that Charity would not be reopened. "He had been inside Charity and said it would be ready to go in a week or so. Then it didn't open. And that—that was bad," Lutz says.

Charity Hospital opened in 1736, financed with money left in the will of a French sailor who died in New Orleans and believed there should be a facility to care for the city's indigent. It was rebuilt numerous times before its art deco structure on Tulane Avenue was erected in the 1930s. Almost 75 percent of Charity's patients were black and 85 percent made less than $20,000 a year, according to Health Affairs, a peer-reviewed health policy journal.

Charity had over 2,000 beds and dealt with the outcomes of the city's violent crime every day: overdoses, gunshot wounds, stabbings and treatment for the mentally ill were handled with military precision. Big Charity, as it was often called, also became the primary health care provider for those without insurance: In 2003, 83 percent of its inpatient care and 88 percent of its outpatient care were uncompensated and given to the uninsured.

When the electricity went out during Katrina, Charity's doctors and nurses used handheld breathing apparatuses to keep dozens of patients alive. They painted sheets and draped them outside the windows, a reminder to helicopters passing by that they were alive and needed help. "9 West has a big heart, Katrina can't tear us apart," read one of these banners.

But a month after the storm, the building was little more than Katrina's largest tombstone. Though Charity had suffered minimal damage, state officials ordered it closed on September 30, 2005, without even a walkthrough. Nine days earlier, three floors of the hospital had been scrubbed and declared ready to use by the military. When state Treasurer John Kennedy toured the building, he said he thought the hospital was "just fine"—its biggest issue was flood damage in the basement. "They could have opened it back up. They just needed to turn on the electricity," Kennedy says.

That didn't matter. Charity was on some powerful people's hit lists long before Katrina. In the months before the hurricane in the summer of 2005, state legislators discussed a plan to knock down Charity and put up a Louisiana State University medical center and a Veteran Affairs hospital. Unlike Charity, the LSU medical center would be privatized.

LSU had managed Charity before the storm, but some high-ranking officials didn't love the hospital's altruistic business model. "Some [legislators] charged LSU '[favored] its educational missions above providing hospital services to the indigent,'" said a 2012 University of New Orleans study. LSU wanted its new hospital, and LSU was used to getting what it wanted. "People in New Orleans joke that LSU is the fourth branch of government in Louisiana," Alexander John Glustrom, director of the 2014 documentary Big Charity: The Death of America's Oldest Hospital, tells Newsweek. "The decision not to reopen Charity went all the way up to Governor Kathleen Blanco, but it wasn't necessarily her who masterminded the plan."

Nor was the decision up to the people of New Orleans: A poll found that 83 percent of locals preferred LSU keep Charity open as a public hospital. Public health care is vital in this town: Before Katrina, 21 percent of Louisiana residents were uninsured—the third-highest rate in the nation. There was also the issue of funding: The hundreds of millions of dollars needed to build the new medical center weren't in the state's budget, and whether legislators and the university liked it or not, Charity was still fully operational. LSU used Katrina as an excuse to skirt both challenges.

A closed-door arbitration panel settled on a FEMA payment of over $470 million for damage to Charity, but that money would go toward the new medical center. The full cost of the new facility was $1.1 billion, and the new hospital, University Medical Center New Orleans, didn't open until August of this year. "We could've gone back into Charity and rehabbed every single room there, and got it back going easily for half a billion," Kennedy says. "Probably less."

Some, however, were happy to see the place go. "Charity was the place of first resort and last resort. People that needed preventative care had to sit there for 12 to 13 hours," Mayor Mitch Landrieu says. " It was a question of whether we were going to build the city back like it was or build it back how it should've been done in the first place."

But to Lutz, a New Orleans without Charity isn't New Orleans. "I fell in love not only with the patients but with the long-term employees there.… It was a real culture, from the elevator operators to the nurse's aides to the charge nurses and administrators," he says. "The powers that be at LSU didn't care about the emotional side of things. It was just about where they can get the money and whose pocketbook they could suck it out of."

A Smaller, Whiter, Richer New Orleans

"If the federal government does nothing, Louisiana will become whiter and richer," then-Representative Barney Frank said of New Orleans's housing situation in January 2007, a year and a half after Katrina. "Because, well, not only black people needed housing assistance, but they were predominantly the ones who needed it. So by simply not doing anything to alleviate this housing crisis that was so greatly exacerbated by Katrina, they achieved—they get a hurricane for the ethnic cleansing. And their hands are clean because all they're doing is not resisting it."

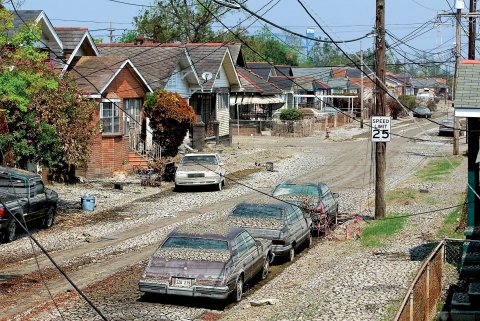

New Orleans officials had first discussed turning the neighborhoods hit hardest by the storm into green space just a few months after Katrina—and insisted it was merely coincidence that most of those communities were black. On December 14, 2005, a headline in The Times-Picayune sparked a fierce debate: "Plan Shrinks City Footprint." A group of well-to-do business people, all appointed by Mayor Nagin to the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, had endorsed a plan to turn several "abandoned" neighborhoods—New Orleans East, Gentilly, the Lower 9th Ward, Lakeview, Mid-City and Hollygrove—into green space. The commission ignored the fact that many of those neighborhoods were not, in fact, abandoned. Their plan contained a potent mixture of racism and ignorance: It seemed odd to incensed locals that the talk of "reclaiming" neighborhoods didn't reach the affluent Garden District or the tourist-heavy French Quarter. It was just the blackest, poorest, most crime-riddled neighborhoods that New Orleans sought to disappear.

As the mayor, governor, Congress, the president and Frank debated the housing crisis in New Orleans, residents and volunteers started rebuilding. Eventually, money from Road Home, a government payment system for homeowners devastated by the storm, eked through the pipelines and insurance companies reluctantly settled.

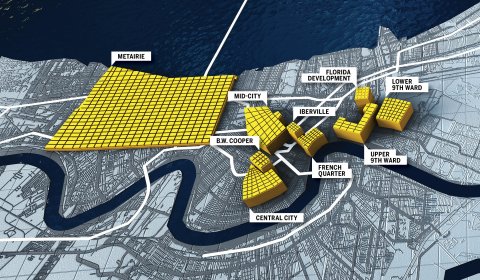

Ten years on, 40 of New Orleans's 72 neighborhoods average a 90 percent population recovery rate. Sixteen of them have more residents than before the storm, and 15 are about the same, since they weren't flooded. Four neighborhoods, however, have less than half of their pre-Katrina occupancy: B.W. Cooper, Florida Development, Iberville and the Lower 9th Ward. Just 36.7 percent of the Lower 9th's population returned.

Rampant fraud and bumbling bureaucracy made moving back into these neighborhoods difficult. Laura Paul, executive director of LowerNine.org, a charity organization focused on rebuilding that neighborhood, estimates 80 percent of the residents she helped fell victim to contractor fraud.

Though the road to recovery is long in these neighborhoods, what Frank referred to as "ethnic cleansing by inaction" has been mostly avoided. A study by the New Orleans Data Center determined that while the African-American population had decreased as of July 2013, so too had the white population, while the number of Hispanic residents was on the rise. In 2000, African-Americans made up 66.7 percent of New Orleans. In 2013, that number was down to 59.1 percent.

Paul hopes to get more help from city officials in the next decade. "At some point, the city needs to step up with significant tax credits here—to get grocery stores, to get businesses, to get the streets fixed," she says. In the meantime, a postcard delivered last Christmas assures her that "the city of New Orleans will soon begin repairing Katrina damaged streets in our neighborhood." She's still waiting.

The Longest Road Home

Mike Cooper was too exhausted to flee New Orleans when Katrina rolled in, so he went home. He had just worked two shifts on the Wheel of Fortune set as a stagehand. (The show had come to town with a custom-made French Quarter set that needed numerous tractor trailers.) Once the crew learned of the severity of the storm, production was shut down, and the show's stars, Pat Sajak and Vanna White, were whisked away. The mayor ordered an evacuation.

Cooper lives in Lakeview, one of the areas slammed by the storm that was almost turned into green space. His house is eight blocks away from a levee breach and six blocks from Lake Pontchartrain; it filled with 12 feet of water during the storm, and Cooper stayed in his attic to escape drowning. "You're like a rat: You're looking for higher ground," he says. "I kicked a hole in my roof as it was getting very hot in the attic. I remember thinking, This is something else I'll have to fix—bitching at myself that I was kicking a hole in my own roof. I got on the roof, looked around and started to realize that hole was the least of my worries."

Several days after the levee broke, Cooper was rescued by two men in a boat. He stayed with friends and relatives in Louisiana and Mississippi for a few weeks before making his way back to New Orleans in late September. He set up temporary camp with friends in the French Quarter and got to work on his house while Washington, D.C., argued with the state legislature in Baton Rouge, which in turn argued with Nagin, who consistently ignored his advisers. "I was the only person I could see [rebuilding]," Cooper says. "Initially, you're just throwing out belongings. Everyone's house looked like a spin cycle. Everything had to go." The Bring New Orleans Back Commission had suggested preventing Cooper and his Lakeview neighbors from rebuilding because of their neighborhood's low elevation. But Cooper was adamant that rebuilding was the only thing that would keep him together in an otherwise difficult time.

By February 2006, Cooper had a FEMA trailer to live in. "It was creepy, but it allowed me to work on my house," he says. Cooper gutted his home, and a friend taught him to run wiring and plumbing. Then he taught himself how to lay tile and put up Sheetrock. "I worked on my house seven days a week, eight, 10, 12 hours a day. I had a mission, and I wanted my house back together." By 2007, Cooper was living in his home again. "The godsend to help me finish my home was Road Home money."

Launched in June 2006, Road Home was, in theory, a simple system: The government would pay the difference between a home's pre-storm worth and the insurance payout the homeowner received, up to $150,000. Cooper was so grateful for his Road Home check that he sent Governor Blanco a thank-you note.

But Cooper's success story is rare. Road Home was imperfect from conception to payout, and Blanco was widely criticized for its failures. By basing Road Home on the pre-storm worth of the home, lower income neighborhoods received smaller payouts—even if the home damage was the same. The same areas Frank accused the government of trying to cleanse were, perhaps unsurprisingly, also those least aided by Road Home.

Soon Road Home had a lawsuit on its hands. "African-American homeowners in New Orleans are being unfairly prevented from reclaiming their homes by the discriminatory design and implementation of the Road Home program," John Payton, the president and director-counsel of the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Center, said in a November 2008 statement when the suit was filed. "African-Americans are facing huge gaps between the amount of their Road Home grant awards versus the cost to rebuild their homes when compared to their white counterparts." The center represented a potential class of over 20,000 homeowners.

The lawsuit was settled three years later. Eligible homeowners received supplemental grants totaling $473 million, which provided relief to over 13,000 homeowners.

Then there was the incompetence of ICF International. Louisiana paid the Virginia company $900 million to manage Road Home. According to the book Katrina After the Flood by Gary Rivlin, the company was spending millions to fly representatives back and forth. The application had more than 50 steps, though it was cut to a still-unruly 43. At the time, the company had just gone public and was awash in the economic bounty of government funding. By January 15, 2007, Road Home had received almost 99,000 applications. It gave out only 177 payments.

The onerous approval process required a variety of documents flood victims generally didn't have: deeds, purchase paperwork, mortgage statements and the like. Katrina had washed them all away.

John Lopez and his wife, who lived on the lake and lost their home in the storm, submitted their Road Home paperwork numerous times, as did many of their friends. They'd check in once a month: at least a half-dozen check-ins and seemingly endless time on hold. Always, they say, Road Home would demand a document they had already sent.

"I handled the homeowner's insurance, and my wife would handle Road Home," Lopez recalls. "I'd call the company, and my wife would coach me—we would take turns calming the other person down." Their home had been destroyed, and the insurance company offered $3,800 for it. "It was one of those checks you don't cash—you hang it on a wall," he says with a bitter smile. Eventually, they received both a proper insurance settlement and Road Home money. Still, they weren't able to go back to their home until 2009. Though Road Home was a bumpy ride, it's the primary reason many New Orleanians were able to return: The program ultimately paid out almost $9 billion to 130,000 residents.

Lopez and his wife had the patience to outlast Road Home and their insurance companies, but many others did not. They estimate only about 60 percent of their neighbors have returned. Many never came back, overwhelmed by the bureaucracy, the paperwork and the low-balling claims adjustors.

Big Charity

"One of the blessed things about the event was the people who reached out. Out of a catastrophic event came a beautiful thing," Landrieu says of the charities, donors and faith-based communities who helped rebuild the city. "It was angels among us. People lost the sense of themselves and helped other people."

Some charities—Lower Nine, Make It Right, Habitat for Humanity and many others—were angels. They asked the people of New Orleans what they wanted, and then got to work to help them get it. While government funding came with strings attached, political motivations and a top-down approach, thousands of volunteers focused instead on fixing the city one issue at a time, side by side with the resident they had come to help.

As for Big Charity, it too might still make a contribution to the city it nurtured and healed for decades. One development company has imagined the Charity Hospital building as apartments, retail space and medical offices. Knocking it down would certainly be a waste, as the concrete structure has proved it can withstand the worst nature and man have to offer. "If they do turn it into condos, I'd be interested in buying one," says Lutz. "Especially if it was on Five East, where I learned to be a doctor."