It's a Tuesday evening at the end of March, and Andy Golub is in his element.

Clad in jeans and an intricately patterned blue shirt, he's onstage at the tiny Gene Frankel Theatre in Manhattan, painting. Seventies music, from Joni Mitchell to Rodriguez, floats from the stereo. There's a murmur of mostly male fans and photographers scattered around the seats. And Golub's canvas is a living, breathing (though, to her credit, not really moving) art student named Dylan.

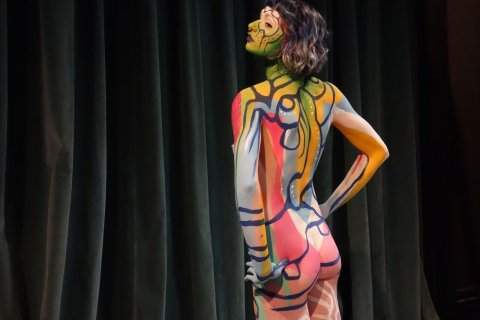

Golub is New York's most prolific body painter, and Dylan is one of his favorite models. "Every time I've painted Dylan I got a good painting," he says from the stage. (She shares the fondness: "I always feel a good energy with Andy. I feel like I can read him well.") Silent and expressionless, Dylan is nude except for a pair of black pants. A man sits down next to me and starts sketching her. Golub paints a yellow dagger down the center of her torso, black branches across her face, light blue circles over her breasts. A white spiral down her legs, dots across her back.

It's a little like watching PBS maestro Bob Ross chip away at a snowy mountain, except every so often the canvas exhales or whispers to Golub and you're reminded that she is a human being who's probably cold and tired of cameras flashing in her direction. (She's not, thankfully, ticklish.) Then the remaining clothes come off and, within an hour-and-a-half, the model's nude figure is a gleaming wonderland of weaving, jungle-like stripes and colors, from curly, blue-tinted hair to blue- and green-striped feet. She poses for the cameras. This time the flashes are welcome.

Golub bears the distinction of being one of New York City's few painters to have been arrested—at least recently—for his work. In fact, his rather public battles with the NYPD have made him a favorite for the tabloids and city blogs. It's not what he paints that offends—it's what he paints on: people. Naked people, of any body type or gender; most of them are not professional models. And in public, too—Columbus Circle, Times Square, wherever. If you're daring enough to strip and patient enough to stand still, he'll turn your bare human form into a psychedelic vessel of painted patterns.

Like Dan Smith and the sinister-seeming Dr. Zizmor, Golub's eccentric public presence and persona have catapulted him toward fringe-level New York City icon status. But from an art-world perspective, his work is entirely ephemeral. You can't stick a painted model in a museum. Golub doesn't even think photos are sufficient to capture his work. What's it like, someone asks from the theater seats, to create art that literally disappears down the drain when the model steps in the shower? He compares it to music.

"With music, it's all about time," Golub replies. "Art seems to be something that doesn't have an element of time…. It's all about the moment. It's all about the experience of seeing the art."

But he likes the fleeting element; as Axl Rose would say, nothing lasts forever. "The idea of it being transitory—I think it is a neat sort of element that you don't get with art so much," Golub says. "People capture it with photos. But everything in life is an experience."

Golub didn't invent this.

From ancient tribes in Asia and Africa (where humans are believed to have adorned their bodies with clay images of gods and war) to the 1933 Chicago World's Fair (where inventor Max Factor Sr. was arrested for decorating model Sally Rand in his newly minted movie makeup), body-painting has a long and illustrious cultural trajectory. The art form hit the mainstream with a 1992 Vanity Fair cover starring Demi Moore in a painted-on suit; by 2000, body paint had become a regular feature in Sports Illustrated's annual Swimsuit Issue.

Difference is, Golub isn't satisfied with art-fair exhibitions and photo shoots behind closed doors. He likes to bring his work—and the NSFW process—into the most public of venues, an aspect that has caught the attention of thousands of tourist passersby and the NYPD. And he takes it to extremes. On Saturday, he's hosting the second annual NYC Bodypainting Day, a convergence of 100 fully nude models and 75 painters on 47th Street in Manhattan. His plan is to lead a naked march to the United Nations once the models are painted.

"When I'm out in public, in Times Square or whatever, it's this confusing thing to people," Golub says. "They're so not used to seeing it that they need someone to say it and confirm it. People come up and they're like, 'What's this for?' And I'm like, 'It's public art!' They're usually pretty satisfied with that answer."

Golub, who is 49, lives just north of the city in Rockland County, where he has served as chair of the Art in Public Places Committee, and was educated further upstate at Albany State University. With curly hair and a wardrobe of baggy shirts and jeans, his looks are much more typical than his line of work. He didn't particularly expect to take this path, either—he started out as a business major and art minor before flunking an important business test and deciding to swap the two. He spent some years teaching in the public school system, and later he became fascinated with painting nonconventional objects: rocks, shoes, tables, even cars. It was when he tried painting a human-shaped mannequin that the lightbulb went off. He mentioned the idea to a friend at Artexpo New York in 2006 and got connected to some models. He gave body-painting a try.

"I remember just seeing my art walking around was this weird experience," Golub recalls. "It made me feel like I should do more of it."

He did, and things escalated quickly: painting in public. Painting fully nude models. Painting fully nude models in public. Painting a lot of fully nude models in public, all at once. Then: "Why not a large girl? What I realized when I started painting some large women is it actually changed the whole art."

Golub found that people were most shocked when he started recruiting male models. "If you paint men in public, people look at it as sort of a gay kind of thing. It was pretty clear that people were like, 'What are you doing? This is crazy.'" Those reactions frustrate Golub, who describes his work as "the opposite of sex." ("I'm showing in the middle of Times Square, in an environment that's filled with sexual advertising, someone who's using the body and creating art," he insists.)

Then came the police drama. Golub has spent more time than anybody fighting for the right to paint naked models in New York. Public nudity is legal in the city, as long as it's part of "a performance, exhibition or show." But in 2011, he and two of his models were arrested. Golub spent about 25 hours in jail. Another model, Zoë West, was arrested in a similar incident later that summer. Civil liberties attorney Ron Kuby took on Golub's fight pro bono and won. "I knew I was in the right," Golub says, but when the charges against him were dismissed, the condition was that he and his models would be arrested again if he tried painting fully nude models during the daytime. (A pointless restriction, one model laughs—"It's always daytime in Times Square.") He played by those rules for a few years. But the implication that his work wasn't fit for children's eyes irked him.

So Golub reached out to the New York Civil Liberties Union, which contacted the city on his behalf. New York officials soon conceded that Golub can legally paint naked men and women in public any time of day. (Three caveats: He can't do it in front of a Toys R Us; he has to announce where and when it's happening in advance; and his models are required to leave their underwear on until right before that area is painted.)

The artist celebrated by securing a permit from the parks department and planning the first NYC Bodypainting Day in 2014. He's still harassed by the police on occasion, but the cops in Times Square recognize him and his victory, and Golub says he's more interested in painting than fighting the law anyway.

So what's it like to strip and get painted? And why is Golub so flooded with fresh volunteers?

Every model is different—he repeats this a lot. "You can feel people who are positive and people who are negative," he says. He's fond of saying that it doesn't matter what a person looks like but what their "spirit" is. With Dylan he gets a "good energy"—when he paints her, he can feel each of her muscles relax—but there are times when he can tell the subject isn't in the right state of mind. Some are more interested in a sexual experience than an artistic one: "Their motive is not really about expression. We're sort of in a different place." Others are a little too into the attention, and the constant chatting or mugging for the camera can interfere with Golub's work.

For the model, as with most things in life, results may vary. At best, the experience could be a life-changing shot of body confidence, maybe a stimulating new hobby or secret pastime. At worst you could outrage your parents, get paint on your bed—maybe wind up naked in a police precinct.

So went the adventure of Zoë West, a professional model who has plenty of experience striking nude poses. There were cops on the scene the whole time West was painted in busy midtown Manhattan in 2011. They stood by bemusedly when the then-21-year-old removed her black G-string but pounced after Golub's work was finished, arresting West and hauling her, naked, into a police van.

West remembers being handcuffed to a bench in the juvenile delinquents room for about 20 minutes before being handed some clothes. Her thought process: "How did I get here? How is this my life?" She laughs. "It was nerve-wracking, but I knew that I was protected." Golub had warned her in advance that an arrest was possible but assured her the charges would be dropped, which they were. As a bonus, West's ordeal blew up the tabloids, inspired a New York Post cartoon and later landed her a nice payout from the city. If West were pursuing a career in, say, investment banking, those NSFW Google results might have been a problem. But she was thinking about pursuing modeling full-time, and the publicity was the boost she needed.

"I'm always thankful that I had that experience with him," West reflects four years later. "Because I'm going to remember it for the rest of my life. And it really kickstarted my career in a big way."

For others, the rewards of body-painting are more personal than professional.

"I'm a naturist, but it was still a totally different experience to be painted in public," says Felicity Jones, who runs the nudist organization Young Naturists America. "It's, like, transformational. I'm still myself, but I'm this work of art."

Golub has worked with models of widely varying physical shapes and health conditions. Recently he received interest from a person with Cerebral Palsy and another potential model in a wheelchair. Several years ago, he visited a hospital to paint Fredi Grieshaber, a 65-year-old woman with Stage IV metastatic breast cancer. In a video capturing the moment, Grieshaber cries and says she's "going out with a bang." "It's a very freeing and liberating experience," Grieshaber says as Golub's paint livens up the hospital-gray setting. She died about two months after it was filmed.

Kiki Alston-Owens, a 41-year-old woman from Staten Island, says that the joy of being painted has helped her to cope with depression after losing nine children. (Doctors still don't know what occurred during her pregnancies, or after, to cause her babies to die.) She has modeled for Golub twice in Times Square and twice during Halloween painting events. "When I'm out there, the paint becomes a barrier from the hurt, the pain, the sadness, the stress," she says. "Everything that may be going on in my life. Once that paint is on, it's like a whole new me. It's like everything is absorbed in the paint."

Alston-Owens put on weight after her losses and now weighs around 250 pounds. She finds it empowering to be a plus-sized model in public venues. "Just seeing their faces is like, 'Wow! She really don't have no clothes on!'" Passersby stare like a deer caught in headlights. When the cops are nearby, she says, they might wait an hour before telling a thin model to get dressed. But with her, "within five minutes, it's like: 'That's nasty. You need to cover up.'"

She won't be obeying those orders. She's now raising money to afford a trip to Amsterdam so she can participate in a body-painting event there in August.

"Body-painting helped to bring me out of my closet, out of my pain, out of my home. It helped me to get myself out there and exposed," Alston-Owens says.

"It helped me to start seeing that even though my children aren't here, there's still beauty in me," she adds. "That this weight, this stomach, these sagging breasts are not something that someone else will look at and say, 'That's obesity. That's nasty.' This is my story of survival. There's a message behind all of this fat. There is a survival struggle."