"We are getting ready to embrace a hydrogen society," said Tokuo Fukuichi, president of Lexus International, as he unveiled the brand's new concept car at the Tokyo Motor Show in late October. Sleek and shiny, the LF-FC could have been just another of the many luxury sports cars glittering under the convention center's fluorescent lights. But the overflow crowd didn't come to look at sheet metal. The real draw lay closer to the chassis: a fuel cell stack that powers the car by converting hydrogen into electricity. Unlike gasoline engines, which send a noxious cocktail of gases out the tailpipe, fuel cells emit nothing but water vapor.

Lexus, a division of Toyota, was not alone in using the Tokyo stage to promote a hydrogen-powered future. The parent company showed the FCV Plus, which plugs into a local power grid to generate electricity for a community, while Mercedes-Benz displayed its Vision Tokyo minivan, which runs on a combination of hydrogen and battery power. Honda presented a close-to-production version of its Clarity Fuel Cell, expected to go on sale next year, and Toyota brought its Mirai (the Japanese word for "future"), which launched in Japan in December 2014 as the world's first mass-produced fuel cell vehicle and began deliveries in California this past October.

The enthusiasm for fuel cells goes beyond their futuristic sci-fi appeal. Environmentalists have called to cut dependence on oil, and world leaders are now deliberating on how to meet June's G-7 summit agreement that promises to phase out fossil fuel by the end of the century. Achieving that goal will require a massive remake of the global auto fleet. But the technology for doing so is at a crossroads.

Electric vehicles, such as the Tesla Model S, Chevrolet Volt and Nissan Leaf, have gotten the glory as early alternatives to the internal combustion engine, but several carmakers, led by Toyota and Honda, say fuel cells will change how we drive, letting us bypass gasoline entirely and travel for longer distances than electric vehicles would before they'd need to recharge. Instead of gas, drivers will fill up on hydrogen at their local refueling station and go more than 300 miles on a single tank. Toyota already has 1,500 orders in Japan for its first 400 Mirais, and the waitlist stretches two to three years.

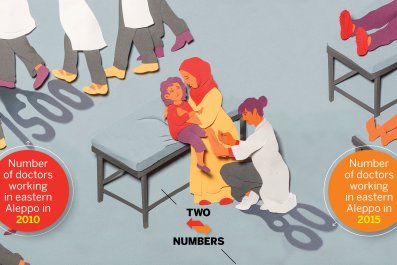

The call for hydrogen assumes, however, that fuel cell drivers will live near a hydrogen fueling station. Right now, that's pretty unlikely. In the U.S., there are only 15 of them: 13 in California and one each in Connecticut and South Carolina. And only four of the stations in California operate at the retail level, accepting credit card payments. The remaining stations are part of a legacy network that can be accessed only by using a code from the carmakers (Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Mercedes and General Motors) that have put small, experimental fleets on the road over the past 10 years.

On the other hand, the growth of the refueling network is quickly accelerating, in large part because the California Energy Commission has earmarked hundreds of millions of dollars to develop the network and hydrogen storage systems. By the end of 2016, California will see 46 stations open. That's still well short of the 100 stations—located in five early-adopter regions, including Silicon Valley and the West Los Angeles and Santa Monica area, and clustered so they're at most six minutes' driving distance apart—the commission has determined the state needs to make the technology viable, but it's a start.

Meanwhile, other states are beginning to support fuel cell vehicles. The governors of Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont have committed to putting more zero-emission vehicles, and the refueling infrastructure to support them, on the road by 2025.

Carmakers are chipping in too. Last year, Honda and Toyota funded the startup FirstElement Fuel based in Newport Beach, California, with $13.8 million and $7.3 million, respectively, to help cover the cost of stations in California. Toyota has also committed to funding 12 stations along the New York–Boston corridor. But "if the stations don't come as we expect," says Craig Scott, Toyota North America's national manager of the Advanced Technologies Group, "we're all going to be sweating."

The stakes are even higher in Japan, where Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has promised to show off "a hydrogen society" for those attending Tokyo's 2020 Summer Olympics. The country is leading the global charge by offering subsidies of up to $25,000 to consumers purchasing fuel cell vehicles and encouraging its government agencies to order them for their fleets. But even Japan is likely to fall short of its fuel cell goals. The country wanted to build 100 stations by March; 28 are up so far, and 53 more are anticipated to be completed over the next six months.

As with much new technology, fuel cell vehicles may live or die on the dent they make in people's wallets. Without the sort of subsidies offered by Japan, the prices for fuel cell vehicles could cause sticker shock—even though the cars are less expensive than the Tesla Model S, whose base version starts just below $70,000. In the U.S., the Mirai starts at $58,325 (including destination fee). Honda said the Clarity FCV will be priced at around $63,000 in Japan, but it hasn't announced the price for the U.S. The cost of the components is likely to decrease as automakers produce more volume, but for now the cars are a luxury buy.

Toyota has allotted close to 1,000 units for the U.S. launch of the Mirai and says it expects U.S deliveries to reach 3,000 by the end of 2017. In addition to California, it'll sell the Mirai in five states in the Northeast, despite the fact that the region currently has only the one Connecticut station. Honda's aspirations are slightly smaller, with an initial target of 200 units for the Clarity Fuel Cell in Japan. It has not announced a launch date for the U.S. Meanwhile, last year, with an apparent eye to the future, Hyundai began leasing a fuel cell version of its Tucson compact SUV that travels 265 miles on a single tank to several dozen customers in Southern California. "We have mass-production capabilities to meet future market demand," says a Hyundai spokesman.

The East Asian automakers' decision to invest billions of dollars in researching and building hydrogen-powered vehicles is at odds with the approach of others that have championed battery power instead. Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk is a vocal critic of fuel cells, famously deriding them as "fool cells" and a marketing ploy that's unlikely to gain traction. But those on the side of fuel cells have their own qualms with battery-powered autos: "The issue for the EV is that it's costly, heavy and takes a long time to charge," says Mitsuhisa Kato, Toyota's executive vice president of R&D. Toyota briefly partnered with Tesla to produce an EV version of its RAV4 SUV, but sales were disappointing. Now Toyota is encouraging new entrants to the fuel cell marketplace, opening its more than 5,600 fuel cell patents to other companies and hoping to benefit from a network effect that will create a density of fueling stations that attracts more customers.

Competitors are watching the Japanese carmakers from the sidelines. General Motors has been developing its own fuel cell prototypes, while Nissan and Daimler AG (Mercedes's parent company) are partnering on a design that Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn said could be on the market as early as 2020. "There's that old joke that fuel cells are always five years away," says Devin Lindsay, an analyst for IHS Automotive in Southfield, Michigan. "But now it looks like we're a lot closer."