Updated | It was just after midnight on the East Coast as another college football Saturday bled into Sunday. Stanford's tireless Christian McCaffrey was in the midst of his latest herculean performance—300 yards rushing, receiving and returning kicks—when ESPN's cameras cut to his parents, Ed McCaffrey and Lisa Sime, in the stands.

Dave Pasch, ESPN's play-by-play announcer, noted that both are Stanford alums with estimable athletic pedigrees. McCaffrey, a former Pro Bowl wide receiver, won three Super Bowls over the course of a 13-year NFL career. Sime was a former standout soccer player for the Cardinals.

As the cameras returned to the action on the turf, color analyst Brian Griese, who is a retired second-generation NFL quarterback, added a note of commentary. "Lisa's dad, that's the real star of the family," Griese said cryptically.

In the past three months, Christian McCaffrey has gone from virtual unknown to Heisman Trophy candidate. A sophomore who wears No. 5 and is the Pac-12 conference's most dazzling all-purpose back since Reggie Bush wore that same number at USC a decade ago, McCaffrey averages 241 all-purpose yards per game. That is 30 yards more than anyone else in the nation.

As a high school athlete in Castle Rock, Colorado, McCaffrey led Valor Christian to four state championships while establishing state records for career touchdowns (141) and all-purpose yardage (8,845). He will likely be a Heisman finalist in his first season as a starter. Yet McCaffrey is humbled by the feats of his grandfather, Dave Sime. "I call him 'the Most Interesting Man in the World,'" he says, referencing the gray-bearded Dos Equis pitchman. "Dave just has so many stories."

Everyone in the McCaffrey-Sime clan refers to its 79-year-old patriarch as "Dave." Nobody refers to him as Grandpa. Or Dad. Or Doctor Sime (rhymes with "rim"). No one calls him an Olympic silver medalist, a Sports Illustrated cover boy or even Duke University's most outstanding athlete of the 20th century (an actual honor he was accorded in 2010). Or, as he was commonly known six decades ago, "the world's fastest human." How much do they even know? "I was in the fifth grade when my PE teacher told me that my dad had once held the world record in the 100," says Lisa. "That's how I found out."

In the summer of 1960, Sime, who was between his second and third years of medical school at Duke University, traveled to Rome. There he accompanied the U.S. team physician on rounds while also working as a CIA operative, attempting in vain to persuade Soviet broad jumper Igor Ter-Ovanesyan to defect.

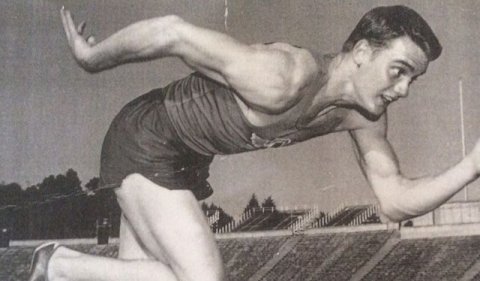

When Sime was not playing doctor or spy, he was busy competing inside the Stadio Olimpico in two events. The red-headed flash earned a silver medal in the men's 100-meter sprint—losing in a photo finish—and he also ran the anchor leg for the USA's 4x100-meter relay team. In that race, Sime overcame a two-step deficit when he was handed the baton and still broke the tape, but the U.S. forfeited the gold medal due to a handoff outside the zone between two of Sime's teammates.

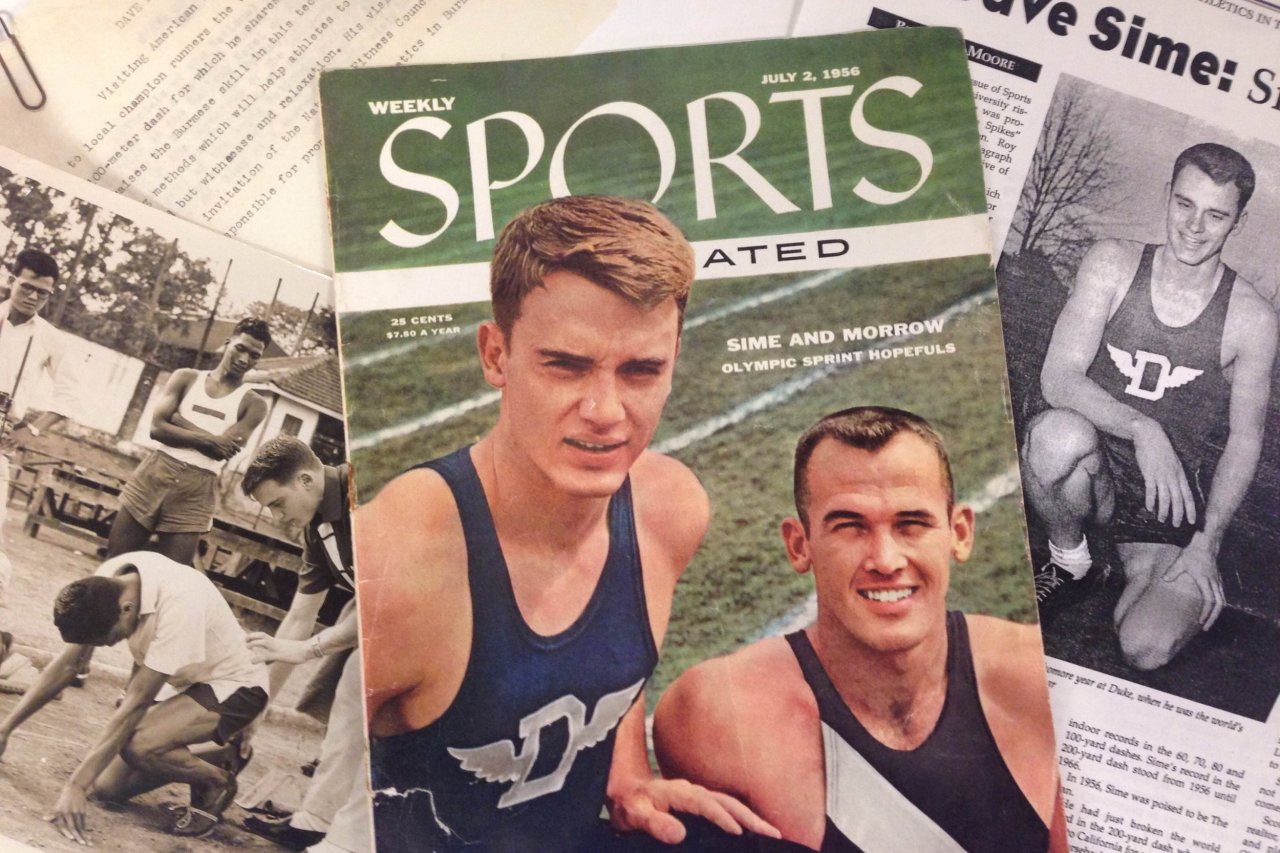

It is worth noting that by 1960, Sime, then 24, was a fading vestige of the sprinter who had set six world records as an undergrad at Duke. "In 1956 they put Bobby Morrow and me on the cover of Sports Illustrated," says Sime. "I never lost a race to Bobby Morrow. But then I got hurt."

After racing at an AAU meet in California in 1956, Sime accepted a friend's invitation to go horseback riding. The Paterson, New Jersey, native had never been in the saddle before. "The horse reared back and fell on my leg," he recalls. "I pulled the muscle as I attempted to free myself."

Later that summer, Morrow won a trio of Olympic gold medals in Melbourne, Australia, in the 100-, 200- and the 4x100-meter relay. He was named SI's "Sportsman of the Year." Sime returned to Durham, North Carolina, where he would play split end on the football team, run track and be an All-ACC outfielder on the Blue Devils baseball team. "I was devastated," says Sime, who had enrolled at Duke on a baseball scholarship and had never even run track before college, "but it was the best worst thing that ever happened to me. When I returned to Duke, I got serious about my premed studies."

Neither of Sime's parents graduated from high school. He graduated in the top 10 percent of his class at the Duke School of Medicine. Over the course of a 40-year career as an ophthalmologist based in South Florida, Sime would be a pioneer in intraocular lens transplants and compile a dazzling roster of patients. Richard Nixon, for one, whose winter home was located just down the block from Sime's on Key Biscayne. Sports-writing legend Jim Murray. Olympian Eleanor Holm. Dolphins quarterback Bob Griese, who in 1972 donned the corrective lenses Sime designed for him and led Miami to the only undefeated season in NFL history.

"Bob used to get overheated, and his eyes would tremble," says Sime, who worked as a team doctor for the Dolphins in the '70s. "The first time I met [Miami coaching legend] Don Shula, we were packing Bob in ice at halftime to lower his body temperature."

The way Sime recalls the story, Shula growled at him and asked if Griese would be able to return to the game. Sime assured the coach his quarterback would be fine. "First play of the third quarter, Griese fumbles and it's a turnover," says Sime. "Shula glares at me, slams his clipboard to the turf and says, 'Sonofabitch!'"

Griese, who along with Shula remains close with Sime to this day, recalls that Sime never mentioned his previous athletic glory. "I knew about it, but most guys on the team just knew that Dave was the team ophthalmologist," says the two-time Super Bowl champion. "They had no idea that the Dolphins' eye doctor could run a faster 40 than anyone on the team."

Once, following an eye exam, a female patient told Sime that her boyfriend, an ex-baseball player, was parked outside waiting for her. "Who's your boyfriend?" Sime asked. The patient told him: Ted Williams.

Sime hustled out to meet the Splendid Splinter, a best-in-breed phenotype who recognized a kindred spirit. The two men became friends. "Ted used to say to me, 'Dave, if I had your legs, I'd have batted .500,'" Sime recalls.

Sime never told Williams that he once hit .506 at Fair Lawn (N.J.) High School. Or that as a 13-year-old he won a speed skating competition staged at Madison Square Garden, the Silver Skates, after which he was presented a trophy by Ed Sullivan. Or that an assistant football coach from West Point named Vince Lombardi paid him a home visit to recruit him. Lombardi brought along a former Army football player named Doc Blanchard, who in 1945 had won the Heisman. "I was all set to go to Army on a football scholarship because I wanted to be a pilot," says Sime (the Air Force Academy did not yet exist). "But during the physical, they discovered that I was color-blind."

Decades later, Sime did become a pilot. He eventually stopped flying when he realized that the pursuit was "99 percent boredom and 1 percent panic." Also, it conflicted with his other hobbies. "I like drinking Scotch better, and the two don't mix."

Dave and Bettie Sime's oldest child, Sherrie, was once the No. 1-ranked singles tennis player at the University of Virginia. As Bettie watched her daughter play one afternoon, another parent marveled at her talent. "Oh, it's in her genes," explained Bettie.

"What brand does she wear?" the woman asked.

The Sime-McCaffrey gene pool is deep enough to induce a case of the bends. Dave has his Olympic silver medal. Ed has his three Super Bowl rings. Christian's uncle, Billy McCaffrey, won an NCAA championship as a member of Duke's basketball team in 1991, scoring 16 points in the finale versus Kansas. Christian's older brother, Max, is Duke's leading receiver this season, with 42 receptions. And one of his two younger brothers, Dylan, is a 6-foot-5-inch junior who is the starting quarterback for Valor Christian.

"We're a competitive family," says Lisa, who refuses to utter "the H-word," as she calls it, when discussing Christian's season. "When Ed and I were on our honeymoon, we started playing backgammon. It didn't take us long to realize that if we wanted this marriage to last, we had to cut out the board games."

Sime, who divorced Bettie and later remarried, has long had a fractious relationship with his younger daughter. "I grew up in South Florida and went to college in Northern California," says Lisa. "You do the math."

The two of them, father and daughter, are positive-charged magnet sides. "Lisa and I have had our ups and downs," says Sime, "because she's single-minded, just like me."

Both of them are funny and feisty. In 1998, Lisa, noting her family pedigree and her husband's disarming speed (particularly for a 6-foot-5-inch Caucasian), told Sports Illustrated, "That's why Ed and I got together: to breed fast white guys."

Sime, meanwhile, has never been the docile, cardigan-wearing gramps. This is a man who took up helicopter skiing in his 50s and brags about how his E-class, 6.3-liter, 577 bi-turbo Mercedes "can go zero to 60 in 3.5 [seconds]." A recent bout with cancer (metastatic melanoma) that spread to his lungs is in remission. "I'll lick it," Sime says matter-of-factly, as if cancer is no more than an outbreak of dandelions on his front lawn.

Griese is continually amazed at his friend's appetite for life. "Dave was always taking up a new sport," he says. "Tennis, biking, swimming: He's great at anything he picks up. [Lisa recalls a humiliating era when Sime took up rollerblading in dolphin shorts.] And Dave's always reading or learning new things. The man is 79 years old, and whatever Alzheimer's is, he's at the opposite end of the spectrum."

Sime does not abide weakness. "I took Max and Christian skiing to Breckenridge when they were little," he recalls. "Max got pissed off and locked himself in the bathroom. So I kicked the door down.

"Then I asked Max if he knew how to swim," he says. "He said, 'No.'"

Sime hoisted up his grandson and tossed him into the pool. Then he jumped in next to him. "Twenty minutes later, Max knew how to swim," he says with a small hint of triumph in his voice.

Lisa sighs. "That's how I learned how to swim," she says. "My dad threw me in the backyard pool every day for a week. And it worked. I really do miss those other three siblings of mine [who drowned], though."

Lisa is never in over her head, either in a pool or in a battle of wit.

Every weekend, Ed McCaffrey and Lisa me fly out from Denver International Airport to watch either Max or Christian play at Duke or Stanford, respectively. Sime has yet to see either of his two grandsons play in person at the collegiate level, even though the older one plays for his alma mater and the younger is one of the most captivating players in the game.

"With the cancer now, I don't like to fly so much," he explains. A little while later, he confides that he'd rather watch the games on television. ("Who wants to sit with a bunch of drunks, throwing beer at me?") And while neither he nor Lisa explicitly says it, a room or even a football stadium may be just a little too confining a space for the two of them to share.

"I do watch all of Christian's games, though," says Sime. "I take a nap beforehand because they come on so damn late. And I talk to him. I call him 'Snowball' because that's what he reminds me of. He's not very big, and he starts off slow. But as he gets rolling downhill, he gets bigger and bigger, faster and faster."

As he continues to wax on about his grandson, Sime begins to sound less like the world's fastest human or even the world's most interesting man. "You're going to talk to Christian?" he asks, sounding like the ideal doting granddad. "Say 'hi' to Snowball for me. Tell my Snowball that I love him."

Correction: This article originally incorrectly stated that Don Shula worked as a team doctor for the Dolphins in the 1960s. He worked there in the 1970s.