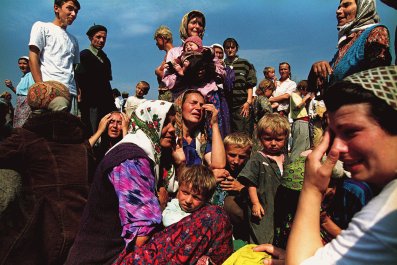

Once upon a time, five beautiful teenage sisters lived in a sleepy seaside Turkish town. After a magical day wandering around with local boys, they returned to their home to find that their innocent excursion had sparked gossip among the neighbors. Worried for their bodies and their prospects, the girls' family locked them inside the house, a "wife factory" created to preserve the young ladies' purity.

Though it seems like a dark fairy-tale, Mustang, the dreamy debut film by Franco-Turkish filmmaker Deniz Gamze Ergüven, subverts the traditional coming-of-age story while taking a jab at the politics of modern Turkey. In recent years, she says, the country's extremely conservative government has attempted to control women's lives, from regulating the number of children they can have to suggesting they not laugh in public (as Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arinç did in 2014). But the protagonists of Ergüven's dark comedy refuse to be suppressed and find ways to use the reasoning behind their imprisonment as their eventual means of escape.

A hit at Cannes, Mustang has been nominated for best foreign language film at the Academy Awards. Ergüven also holds another distinction: She is one of just two female directors whose feature films are nominated in any Oscar category this year, along with Liz Garbus, who directed the documentary What Happened, Miss Simone?

How's the reception to your film been in Turkey?

From family and friends, extremely positive. The reaction in Turkey is very polarized. You have people who love it and hate it. But as the film has more of a life abroad and people fight about the film on social media, the conflict in those fights is exactly the conflict which is in the film. Some people say, "Seeing those girls in front of the camera half-naked, it makes me sick to my stomach." Then another person says, "Well, if you looked at them as kids, you wouldn't say things like this." People view the film, and they see the world for an hour and a half through the eyes of a 13-year-old girl. It's quite an exercise for men. In our history, we're used to seeing through the eyes of men; we know how the world looks to them. So for men, it's a broadening experience.

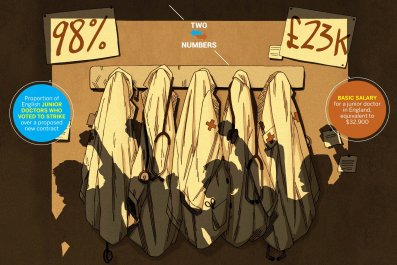

Do you feel like it's getting easier for women to make films?

We're missing out on so many things by not having films by women. It's not just a question of equity—having the same figures, salaries. Womanhood is still something quite exotic. But the fact that we're talking about the [inequity], it's going to eventually change something. As a filmmaker a decade ago, it was so much harder. Even for Mustang, it was hard to trigger trust! We still feel uneasy if we see a woman pilot when we get on a plane, and people do that with women filmmakers too. They wonder if we can land that plane, if they can trust us with that. So it's been harder as a woman filmmaker because of that, but the reactions I had a decade ago were worse.

How do you probe topics that are taboo in Turkey, like sexuality, in the film?

There's an algorithm to Turkish humor. At some point, I couldn't describe it, and then I found the perfect situation to explain it: A few months ago, a director of a university decided he would build a mosque inside the technical university of Istanbul. And the students said, "We don't need a mosque. There's mosques all over the city." And the director said, "No, I had a very long petition and so many signatures of people who want the mosque in the university. We have to build it." And the very next day, students had something like thousands of signatures petitioning for a Buddhist temple in the university.

That to me is the algorithm: Respond with the same absurd logic with which you're confronted.

Have you been following the #OscarsSoWhite controversy?

For me, the Oscar is just the reflection of something which is ever there. The first film I ever wrote took place in South Central Los Angeles, and the characters were African-American. And I had discussions with producers—without any kind of cynicism—saying I couldn't sell a film with African-Americans to Japan or Germany. For me, African-Americans were the most glamorous people in the world, and they said it was urban and for a narrower audience. There is racism, and it's not even just on the production side. It's on the side of who is buying the tickets too.

I think it's great that we have this discussion, but the problem is not the Oscars. Boycotting the Oscars is not the solution. If someone feels underrepresented and gets to go, they have to go. And I feel like proactive steps have to be done at the level of production. That's where you put in very strong actors who are minorities and strong women characters. That's where the act of change is possible.