Americans no longer deserve America. The Founding Fathers' experiment in democracy, forged in blood and scholarship, has failed.

There is no other way to interpret the obscene debate that has enveloped the country since the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Almost before Scalia's body went cold, prominent Republicans rushed to proclaim they would never vote to confirm any nominee submitted by President Barack Obama to fill the vacancy. Their declaration stemmed from a bizarre, anti-constitutional argument that a president should be allowed to have any Supreme Court nomination confirmed only during 75 percent of the executive term of office.

Make no mistake: That is exactly what the Republicans are saying with their "a president shouldn't have the power to select a justice in an election year." (Or is it just a Democratic president?) But why stop there? There are two elections in every presidential term, including the midterms, when control of the Senate is up for grabs. Shouldn't the public—using the Republicans' absurd "electoral year" argument—have a voice in deciding who can and cannot be confirmed by letting elections happen first?

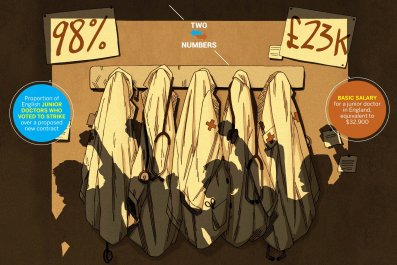

For an example of how respect for the Constitution has decayed, look at the selection of Scalia, whom President Ronald Reagan nominated in 1986. His hearings began in August, about three months before the midterm elections. At the time, Republicans controlled the Senate, but polls showed the Democrats were almost certainly going to gain the majority in November. The Democrats had the power to filibuster and delay. Instead, Scalia was confirmed on September 17 by a vote of 98-0, just 49 days before the Democrats won control of the Senate by a wide margin. Forty days before the election, the Senate also approved Reagan's selection of William Rehnquist, who already sat on the high court, as chief justice.

After the 1986 midterms, the Senate's Democratic majority could have refused to confirm any more nominees in election years. But they didn't. Instead, they unanimously confirmed Anthony Kennedy in 1988, another election year. So two of Reagan's selections for new justices—and his choice of chief justice—were confirmed not only during the run-up to a midterm election but also in a presidential election year.

It's not that Democrats are inherently moral. Reagan's first nominee for that Supreme Court opening ultimately awarded to Kennedy was Robert Bork, a brilliant man supremely qualified for the job. Democrats ripped him to shreds over ideological differences in ugly Senate confirmation hearings that brought disgrace to the party and sped the politicization of the court.

But Republicans have taken partisanship and perverted it into a pure power grab that has crippled the judiciary. Since gaining control of the Senate in 2015, GOP senators have largely stopped filling vacancies on the 12 federal appeals courts, which is also virtually without precedent. When faced with a Senate led by Democrats, Republican presidents since Reagan have been able to appoint between 10 and 18 appeals court justices during their final two years in office. During the years Obama has had a GOP majority in the Senate, only one has been confirmed; about a dozen seats are empty because the Republicans have refused to allow hearings on nominations. Now Obama will likely end the last two years of his presidency with the fewest appointments to the appeals bench since President Grover Cleveland left office in 1897—and that's only because there were no vacancies at the time.

While Republicans wave the Constitution, many of them seem to have no idea what the founders intended by giving the Senate the power to confirm nominations. Intent on forming a government unlike any other in history, these men spent enormous amounts of time discussing the issue of judicial appointments: Should they be selected by the president alone? By the Senate? By all of Congress? Finally, the founders settled on the concept that the president nominates and the Senate has the duty to "advise and consent." The division of powers was based on the idea that leaders with the capacity for shame would be compelled to act with integrity if both kept an eye on the other.

The writings of the founders make it clear that they designed checks and balances to prevent power grabs—in other words, confirmation was intended to be a shield to prevent presidents from nominating cronies, not a sword to stop the White House from having any power to fill openings in the judiciary. The Federalist Papers—the collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay, the first chief justice of the Supreme Court—are the strongest in establishing the motives for including "advise and consent" in the Constitution. Hamilton wrote the relevant portions, which show the purpose of confirmation is to avoid granting the president the unchecked powers of a monarch.

But Hamilton never conceived, based on his writings, that a Senate would attempt to seize those absolute powers by refusing a confirmation purely for political purposes. In fact, Hamilton never imagined that the confirmation process would result in many rejections at all; the idea was simply to prevent a president from submitting judicial nominations based on corrupt deals, friendships or patronage. Given the impact on the reputation of any rejected nominee, among other factors, "it is not likely that their sanction would often be refused," Hamilton wrote, "where there were not special and strong reasons for the refusal." That the president had begun the last quarter of his term in office would hardly be considered a "special and strong" reason.

Hamilton did not conceive of a day when warring between parties would virtually stop the passage of legislation and confirmations. Rather, he thought the ignominy of arbitrarily rejecting qualified candidates would keep the Senate in check. "The blame of a bad nomination would fall upon the President singly and absolutely," he wrote. "The censure of rejecting a good one would lie entirely at the door of the Senate; aggravated by the consideration of their having counteracted the good intentions of the Executive."

Hamilton also believed the power of the presidency was vested in the constitutional term of office, not just three-quarters of it, as the Republicans now hold. "As, on the one hand, a duration of four years will contribute to the firmness of the Executive in a sufficient degree to render it a very valuable ingredient in the composition,'' he wrote. "On the other, it is not enough to justify any alarm for the public liberty."

Although skeptical about man's capacity for wisdom, Hamilton was still too optimistic to foresee the bloodlust of today's Republicans. John Adams was less sanguine about the emergence of an unprincipled Senate. In 1789, when he was serving as George Washington's vice president, Adams exchanged a series of letters with Roger Sherman, one of the Founding Fathers who proposed the makeup of the Senate at the Constitutional Convention. Adams wrote that he feared the Senate would break into political parties and become too power hungry and diabolical in its attempts to undermine the president and cripple his powers.

"We shall very soon have parties formed; a court and country, and those parties will have names given them,'' Adams wrote. "One party in the house of representatives will support the president and his measures and ministers; the other will oppose them. A similar party will be in the senate; these parties will study with all their arts, perhaps with intrigue, perhaps with corruption, at every election to increase their own friends and diminish their opposers. Suppose such parties formed in the senate and then consider what factious divisions we shall have there upon every nomination."

Pish posh, Sherman replied. The scenario feared by Adams—where wealthy senators would band together corruptly to undermine the presidency—could not possibly occur "without a total subversion of the constitution."

Exactly. Plenty of conservatives are now committed to the idea that simply because a power is in the Constitution, it can be abused by any opposing party in control of the Senate for purely political purposes. They cannot see that they are creating a weapon that will cripple an essential power of another branch of government.

So to hell with it. Constitutional democracy is being destroyed. Let's stop pretending otherwise, allow each party to desecrate government for political advantage and just get the collapse of our country over with fast.