Donald Trump is our brains on GIFs.

Many people who are thoughtful and analytical have a hard time understanding the appeal of Trump's empty but crowd-roiling provocations. But think about the smartphone-driven explosion of GIFs in the past six months.

You've probably seen those three-second video loops pop up on Instagram or Twitter. If you're under 30, you might traffic in GIFs all day long. This year, GIFs are turning into an industry and becoming a whole new language, one that is entirely about emotion and devoid of facts or even a smidgen of context.

See? Just like a Trump rally.

Technology changes the medium, and the medium changes us. GIFs certainly seem to be having an impact, pushing us closer to a post-language society that prefers to communicate by sending a cute clip of a cat playing guitar. Who needs words anymore?

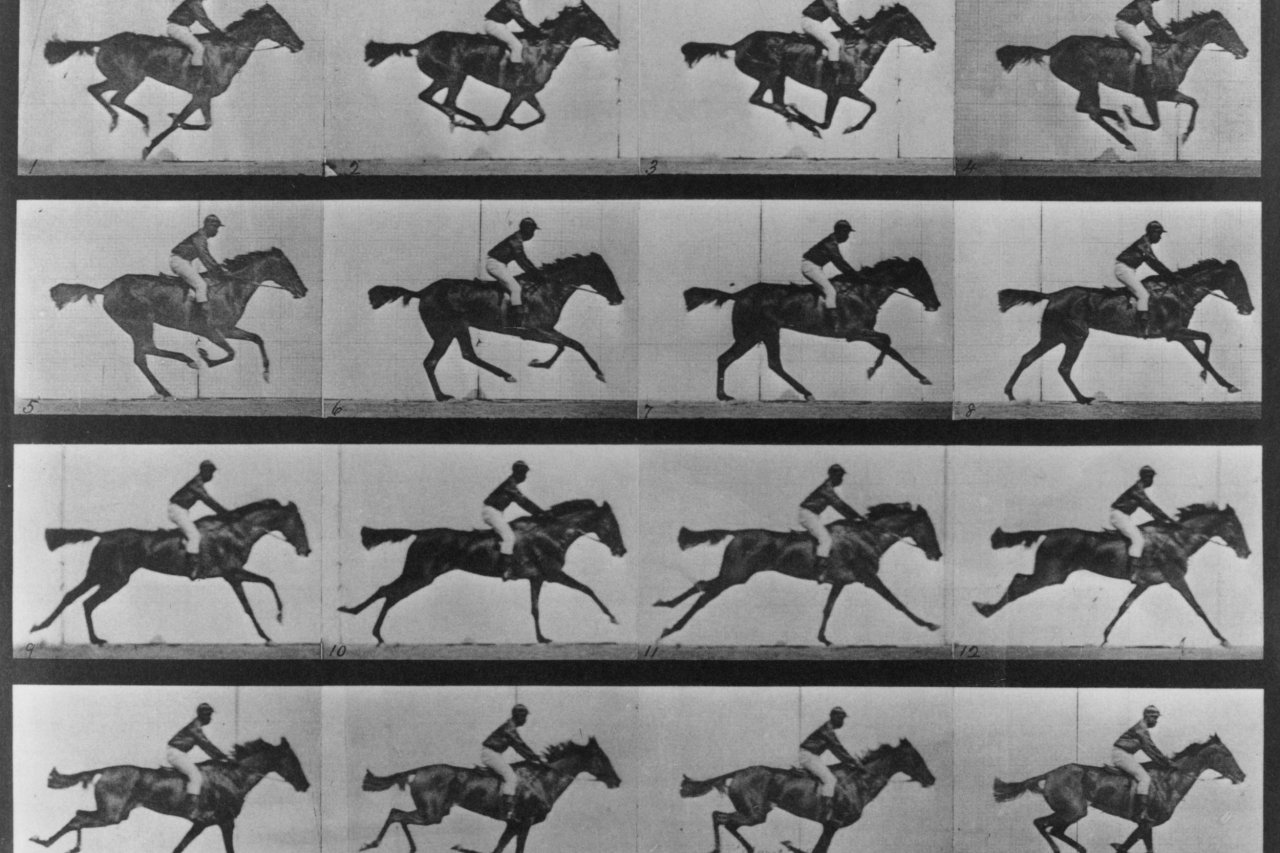

While GIFs are red-hot now, they've been around since dial-up modems, or the dinosaurs, whichever came first. Back in 1987, Steve Wilhite, working at CompuServe, created the first Graphics Interchange Format image—an animated airplane. Online connections were so slow, it would've been nearly impossible to send video across the network. Wilhite's invention could generate a moving image using very little data. The GIF format has powered moving images on the Web ever since.

For decades, GIFs were usually decorations. Now, suddenly, they're becoming communication. The smartphone is a big reason. Phones have small screens that make it hard to read anything of length. We check our phones constantly in short bursts. They're not built for thinking—smartphones are built for getting stuff done and getting to the point.

Short-burst communication in the early days of smartphones meant text messaging. When texting took off, it seemed like a new low in discourse. We saw lots of headlines like this one from the Cleveland Plain Dealer: "Text-Messaging: Scourge of Civilization? LOL." But texting seems epic compared with GIFs.

Most GIFs today are video clips. Wireless networks carry them easily. Smartphone screens display them nicely. But most people didn't have ways to create GIFs, or search for just the right GIFs, or embed GIFs in a message. That's what has changed lately.

Giphy, now the biggest GIF search engine, launched in 2013. It works sort of like YouTube. Type in angry or hockey, and relevant GIFs fill the screen. Click, and you get ways to embed it in a message, blog post or whatever. Giphy, with a $300 million valuation, just got $55 million in funding. The site serves up tens of billions of GIFs each month and is quickly rising toward being one of the most trafficked sites on the Web.

In a next phase, one Giphy investor tells me, the service will be meshed with social media, so as you type each word you'll see a relevant GIF. The idea is that you could stitch together GIFs to convey your message using not actual letters in the alphabet at all.

Other startups are jumping into GIF-giving. Riffsy last year raised $10 million to make a GIF keyboard you can download on your phone. That way, you can just type sentences of GIFs. "We think of ourselves as building this visual language, this lexicon," Riffsy CEO David McIntosh said at the time. Another startup, Daycap, stitches together photos you took on your phone throughout the day and generates a GIF that you can send to your friends, if you have any who would actually like to know what you've done all day.

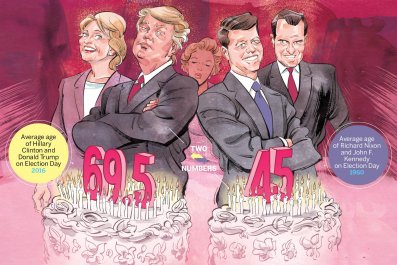

Oddly enough, Hillary Clinton, who gets accused of being too wonky and appealing too little to gut-level emotions, aggressively uses GIFs in her campaign. Trump, who's kind of a human GIF, tends to stick to tweets, which is starting to seem so old school.

Two researchers at the MIT Media Lab are trying to create a GIF genome so computers can readily identify the emotions or meaning behind a GIF. The researchers, Travis Rich and Kevin Hu, say it's a step toward making GIFs into a language. "We realized that they're becoming more and more serious of a medium," Hu said. "And we realized that we could quantify this usage."

Put it all together, and it seems apparent that we're all going to wind up sending out strings of moving images to get our thoughts across. But it seems unlikely that GIFs are going to help anyone understand the pros and cons of sending troops to fight the Islamic State militant group, or ISIS. GIFs are more likely to convey just the emotion of how good it would feel to smack down an asshole.

Of course, every generation sees some new medium as the end of intelligence. Twitter seemed that way last decade. In the 1980s, cable-TV news alarmed those reared on The New York Times. Socrates, around 400 B.C., apparently complained that the written word meant people would no longer have to completely remember everything. Kids weren't going to put in the effort to learn to recite three-day-long epic poems anymore. Sheesh.

Still, there does seem to be a long progression away from complex thought and toward wordless grunts—a complete de-evolution, to borrow Devo's term, of language. GIFs are entertaining, but the idea that more and more people are embracing them as an actual language may tell us a lot about this moment in time, and why a certain candidate can confound the people who think they can defeat him with substance.

Trump supporters may disagree. They might even say, "I guarantee you there's no problem. I guarantee it." But more likely, they'll just send me the GIF.