Updated | History remembers Jackie Robinson mostly as a myth, not a man. He was the humble ballplayer Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey used to break baseball's color barrier, the secular saint who turned the other cheek when confronted with racism. White America has preserved this gleaming image of the icon, but the real Jackie Robinson was far angrier than history remembers, and he continued fighting fiercely for African-American rights long after his playing career came to an end.

This is the Robinson who filmmaker Ken Burns—along with daughter Sarah and son-in-law David McMahon—examines in his latest documentary, Jackie Robinson, which airs April 11 and 12 on PBS. Some myths need to be dispelled, especially in the case of a complicated figure like Robinson, whose work as an activist is just as important now as it was 50 years ago. Interviewing everyone from Robinson's wife, Rachel, to President Barack Obama and the first lady, the Civil War and Baseball director does just that as he explores the misunderstood life of one of America's greatest civil rights pioneers.

Coinciding with the production of Jackie Robinson was the reintroduction of the issue of race into mainstream discourse in America. From Trayvon Martin to Ferguson, to Eric Garner and beyond, the issue has taken perhaps its most prominent role since Jackie Robinson was fighting for civil rights in the '60s. Because race has always been the dominant story of American history, it's also been the dominant story of Burns's work. Few others are able to so astutely draw parallels across generations in order to show what has changed and, more importantly, what hasn't.

After Dylann Roof brutally murdered nine African Americans worshipping inside a Charleston, South Carolina, church in June of 2015, Burns called the city's then-mayor Joseph Riley to ask what he could do. The result was a series of conversations this spring with Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates to discuss race in America today.

"If you look at a lynching photograph from the 1920s or '30s, you are drawn immediately to the African-American corpse," Burns said during one such conversation that took place in March at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas. "But if you look at the people standing around, they're smiling, and some of them are little kids, and those little kids are alive today and perhaps speaking to Dylann Roof and telling him about what he has to fear."

Burns was able to sit down with Newsweek the morning of his talk with Gates. In the back of the near-empty bar of Austin's Driskill Hotel, he spoke with with no less passion, enthusiasm and purpose than he did to a far larger audience in the Austin Convention Center later that day. Though Burns is known for documenting the past, his enegery is just as focused on how its lessons can be applied to the present.

Have you always felt Jackie Robinson is underrated as an activist?

Yes. If you look at it, he represents the beginning of the modern age of the civil rights movement. As we say in the film's introduction, quoting Dr. Martin Luther King, he was "a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom riders." When he [made his major league debut] on April 15, 1947, there had been a lot of civil rights going on in the 20th century up to that point. But at that moment, Dr. King is still a junior at Morehouse College. Harry Truman hasn't integrated the military yet. Brown v. Board of Education hasn't happened. There are not organized sit-ins at lunch counters, although as a teenager Jackie had done that. Rosa Parks is a decade away from refusing to give up a seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus—but Jackie did that in 1944. That's what makes him so seminal.

In some ways, if it's in the 20th century, it's the beginning of the second act of civil rights. He was a major character. [We aimed to] get rid of some of the barnacles of mythology that encrusted around him, the superficiality that our conventional wisdom always suggests. The turning the other cheek doesn't really work as some Christ-like thing if you don't know about his temper, if you don't know about his competitiveness, if you don't know what he was giving up in his own personality to do that.

Branch Rickey was hugely important, but he's not God. He was planning [to bring up] several other people. People had been arguing [for integration in baseball]—black press, leftist press, the Communist Daily Worker—they're pressuring the extremely left-leaning Republican mayor of New York, Fiorello Laguardia, they're pressuring state commissioners. All of that is plowing toward Rickey's plan to do this...That makes for a much more interesting story.

Then there's Jackie's Republicanism, supporting and campaigning for Richard Nixon then pulling off when Richard Nixon doesn't make the call to get King out [of prison in 1960], and throwing his support to Kennedy.

What struck you the most about Jackie's story that you didn't know before you started making the documentary?

It's not one thing. It's the accumulation of a thousand things. Like the layers of a pearl, it's kind of imperceptibly accrued. What it is is something like realizing that [in Burns's documentary Baseball] we had promoted the false story of Pee Wee Reese putting his arm around him. White people want some skin in the game, no pun intended. And maybe the nuances of Branch Rickey, who is hugely important. We already [in Baseball] admitted that he was as interested in the buck as he was doing right. That he could fill Ebbets Field with black patrons, but it was mainly a gesture of civil rights. But to have the other competing stuff…It was easier to tell a story, to tell the singular, "Branch Rickey, this is the right thing to do, I bestow on you my son, Christ-like he comes up and turns the other cheek." That's what we inherit, along with the Pee Wee Reese story. What we don't understand is what America did to him after, and more importantly what the entire dynamics of the civil rights movement did to him while it was happening.

It's interesting that since you started working on this, because of Trayvon Martin and Ferguson and everything that followed, race has become part of the mainstream dialogue in a way that it hasn't been probably since the civil rights era.

It's always been central in my work, and I've paid a price for it. I get a lot of hate mail. "You n*gger lover." Even among friends and scholars, they say, "Why do you focus on race? Why is it always race?" I say, "Look, race is the story of America. It's our original sin." Wynton Marsalis, in Jazz, says that race is the thing in the mythology that the kingdom needs in order to be well. That's a wonderful way of putting it. This is the thing we are obligated to solve, or at least make better, to ameliorate in some way in order to go forward. It's all about this. Even when Obama was elected, people said, "Now will you shut up?" I said, "No, no, no, just watch." I held up the cover of The Onion. It said, "Black Man Given Nation's Worst Job." Watch what will come out of the woodwork.

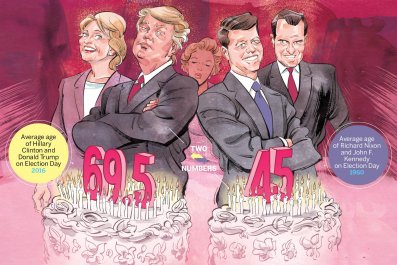

We like to think of ourselves as following Lincoln's idea of "the better angels of our nature." In point of fact, when we are faced with our guilts, they metastasize. They become something else bad. These conversations that Henry Louis Gates and I are having around the country are to try to talk about race and further the conversation. [The massacre in Charleston] increased the sale of confederate flags. Look at Donald Trump's rally, filled with people who are the opposite of the better angels of our society—that's very American, too—who respond with violence and increased discrimination and anger and animosity...

I had a friend who actually said, "Could you knock it off about race?" He has since come to me and apologized. Last year, I think something like 295 out of 365 days an African-American was killed by the police. And we still don't talk about African-American violence on African-Americans.

Was there anything in particular about Robinson's story that you were instantly able to connect to what's happening with race in America today?

The president and first lady did that. It was great to interview them. All of a sudden you realize you have these two couples—four human beings—hurtling through space. Jackie is the first to go through a door back then, and he clearly could not have done it without Rachel. The president is the first to go through a door, and he's saying [in the documentary] that when people are giving you shit for stuff that has to do with the color of your skin, it's good to go home to where people love you and have your back. It's a really moving moment. I began to understand the truth of that there's nothing new under the sun, that human nature never changes. We can make progress. I did get to interview an African-American president—Jackie would have probably thought that would be some far off, distant future, not within his wife's lifetime. That was good. But at the same time, the film is also about confederate flag controversies. It's about integrating swimming pools. It's about driving while black. It's about stop-and-frisk. It's about discrimination. It's about black churches being burned. It's about Black Lives Matter. That, sadly, hasn't changed. It reminds you that our job as human beings, with regard to the question of race, is always there.

Some little girl asked me after The Civil War came out, "What is racism?" at a big event I was doing. I said, "Wow, what a great question." It's probably the horrible flip side of a very understandable human emotion, which is love of one's own. When that metastasizes, it becomes the hatred of the other. Racism also involves power and the relationship over time of whites over Africans in the United States, because they were owned. It has a hugely complicated dynamic and it will never be gone, but we're still nonetheless obligated to try. I think [when you consider] things like Trayvon Martin and Ferguson and Staten Island and Charleston and Oakland, when you've got a Trump inciting violence, it becomes possible to go back to a story which most everybody can agree that we like—the story of Jackie Robinson—and suddenly see how it could be serviceable, how it could become usable for us now. We could take the story of Jackie Robinson and in it see Trayvon Martin and see Michael Brown and see Eric Garner and see all these people.

I called [Charleston] mayor Joseph Riley after the massacre, who is now out [of office] after like 41 years as mayor, and I just said it's really good that the confederate flag has been removed from [statehouse] grounds. Symbols are hugely important and that's a vile and vicious symbol. It doesn't represent people's heritage, it represented their resistance to civil rights. That flag isn't even the flag of the confederacy. It's one battle flag of the army of northern Virginia, and it came into prominent use after 1954. There's only one thing that happened in 1954 that's germane to this conversation, and that's Brown vs. Board of Education. Working it into those state flags is just resistance to Brown vs. Board of Education. It isn't about taking away somebody's heritage. When Fort Sumpter surrendered to the confederacy, they flew a different flag, the official flag of the confederacy. I'd be happy to talk about that flag, but we get out this symbol of hatred. But let's see if we can have a conversation that gets beyond even that.

And Jackie Robinson got pissed off when the flag was raised [as part of a Pee Wee Reese fan appreciation night at Ebbets Field].

And no one understood! It's like, "C'mon, Jackie. C'mon, he's from Kentucky." They're playing "Dixie" and running up the confederate flag. This represents the worst in us. You don't want to throw it away. You want to tell the story. I've done it in The Civil War. But let's be really honest about what it means: that you live in a country that represents to the world that all men are created equal, but—oops!—the guy who wrote that sentence owned more than 100 human beings, and four score and five years later we started killing each other in such great numbers that all the other wars that we have been involved in do not equal the deaths in that war, to perpetuate an institution that says all men are not created equal.

The hypocrisy has been there since the beginning.

Since 1619! We postulate the pilgrims coming for religious and political freedom in 1620. Well, in 1619 the first slaves are brought to the United States, to Virginia.

Speaking of Trump and connecting the dots, is there some sort of antecedent what is happening with Trump right now? How do you put this into historical context?

Yeah. Mussolini and Hitler. George Wallace in the United States. It reminds me of [Trump's] comments about the protesters, earlier, when they were roughed up and he was happy about it. George Wallace, when he was running in '68, Lyndon Johnson traveled to other countries and to American cities, and sometimes protesters protesting the war in Vietnam would lie down in front of his car. George Wallace would say, "If I became president of the United States, that's the last car they would lie down in front of," meaning he would run over them. He was marginalized to a third party, but now this is mainstream. The party of Lincoln.

There was a political cartoon a friend sent to me, I don't know where it originated, it showed a picture of Abraham Lincoln wearing a button: "GOP: Born 1856, Died 2016." This ain't the party of Lincoln. When this guy takes more than a nanosecond to think about disavowing white supremacy, David Duke and the Ku Klux Klan, that is a wink-wink at those people. And they can say, "He is one of us." It's just like when Ronald Reagan opened his presidential campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi, it was a wink-wink to everybody.

So is Trump and how America has embraced him, and all these increasingly ridiculous things that keep happening one after another, not surprising to you in the way that it is to everyone else?

It's easier to hate. It's easier to make people fearful and hateful than it is to do the hard work of reconciliation. People would love to have that. The drumbeat of the Republican Party isn't Trump, he's just echoing it. When he says "birther," it's a polite way of saying the n-word. When Scott Walker says, "I don't know if he's Christian," that's a polite word of saying the n-word. We have heard for eight years that [President Obama] a delegitimate president, even though he got the majority of the vote of the country. They have not respected the office. So what happens is the Republican Party has itself promoted the idea of his illegitimacy, so that everything is wrong.

The drumbeat of the Republican Party isn't Trump, he's just echoing it. When he says "birther," it's a polite way of saying the n-word. When Scott Walker says, "I don't know if he's Christian," that's a polite word of saying the n-word.

You can say, "It's the black person who is to blame. It's those immigrants who are to blame." In point of fact, there is a net loss of Mexican immigrants to the United States. More Mexicans are leaving than coming in, and he wants to build a wall. Mexicans and other Latin and South Americans commit one-third less crime per capita than traditional residents of the United States. We have had 72 straight months of job growth. Admittedly, it has not brought everyone in, but if the president had a stimulus program of the kind he wanted, rather than the kind he was given, you might have had a much greater recovery than what was there. Affordable healthcare has done the "horrible" thing of making sure that 20 million Americans who did not have health insurance have it. To hear people still talk about it as if it's some sort of disaster—I'm waiting for them to tell me where this disaster is. We've got something. It goes back to The Onion newspaper: "Black Man Given Worst Job in the World." They're going to blame him for everything.

Which is why we have Trump.

That's exactly right. He's energized a base that in the positive dimension, Barack Obama energized in '08 and, to a lesser extent, '12. Trump, in the retrograde fashion, is energizing a new base, which bodes very ill for our republic.

Race is something you're plenty familiar with addressing in your work. What was the most challenging part of making Jackie Robinson?

We had Rachel's complete cooperation. In fact, she had been urging me to do this for years. She opened not just the archives of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, but also opened up her heart and gave us some pretty heroic moments, and also some pretty difficult moments that she's gone through. Into every life some rain must fall. For me, it was losing some of the old familiar tropes, and basically outgrowing, not just Pee Wee Reese—that was easy, that was exciting—but some of the other things. Realizing that…I'm a good storyteller and I know how to wrap that scene up in the old way, but what if it was more complicated than that? What if this scene has more undertow? How do you honor that? It wasn't an old dog [with] new tricks; it was saying, "This is really complicated. Let's try to tell it well."

This article has been updated to include additional responses.