In the 2012 movie Skyfall, James Bond brandishes his trusty sidearm, but with a high-tech twist: There's a sensor in the grip that reads palm prints so only he can fire it. The souped-up firearm saves the secret agent's life, and in the real world, similar technology could do the same for thousands. Or so says Ron Conway, an avuncular Silicon Valley billionaire trying to disrupt the gun industry.

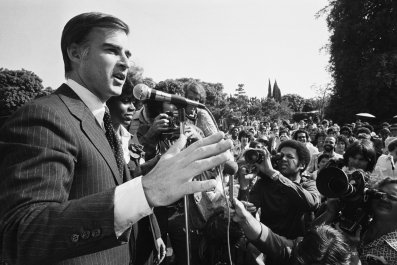

Speaking at the International Smart Gun Symposium in San Francisco in February, Conway exuded the cockiness of a man who invested early in Google, Airbnb and Twitter. "The gun companies have chosen to sit on their asses and not innovate," he said. "Silicon Valley is coming to their rescue."

Conway isn't a gun owner, and for most of his life, he never gave much thought to firearms. But after Adam Lanza shot up an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012, killing 26, Conway created a foundation that has given $1 million to inventors. The goal: perfect user-authenticated firearms.

Today, as gun violence continues to plague America, Washington seems paralyzed, largely due to pressure from lobbyists such as the foot soldiers of the National Rifle Association (NRA). In 2014, firearms killed more than 33,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In that same year, 32,675 Americans lost their lives in automobile accidents. Most experts think it's just a matter of time before the U.S. becomes a country where you're more likely to be shot to death than die in a car, because automobile-related accidents are declining. Conway and others in Silicon Valley think that's instructive. Airbags and seatbelts, along with the legal requirements and social pressure to use them, have nearly cut car fatalities in half, even as Americans drive more and more miles. Smart guns, Conway says, can do the same, whether it's preventing a toddler from firing his father's weapon or stopping a criminal from shooting a police officer with his or her own firearm.

The biggest barrier to smart guns is politics, not technology. Over the past two decades, various gun-makers have tried to push smart gun technology, and gun owners have been wary, fearing the newfangled firearms were little more than gun control in disguise.

The first time the technology seemed ready was in 1996, when Colt unveiled the prototype for a handgun that required users to wear a radio transponder on their wrist, like a Dick Tracy watch. The NRA was strongly opposed to it, says Doug Overbury, the vice president of engineering at Colt in the late 1990s. But the gun-maker was ready to push forward. "Within a year or so, we'll have this as reliable as your radio," Overbury says he told interested police departments.

Yet Colt's smart guns never made it to production. The NRA eventually gave Colt the go ahead, but gun owners shunned the company anyway, afraid of a back door to gun control. By June 1998, other groups were distributing fliers attacking the company's leaders as "detrimental to American-style freedoms and liberties" and calling the guns dangerous at the NRA convention. The lobbying group says it wasn't behind the boycott. But it took a new management team and a turn away from smart guns for the brand to recover.

Today, the NRA says it isn't against smart guns, just laws that mandate gun owners use them. In 2002, one such law passed in New Jersey. Once smart guns become available, licensed dealers in that state can sell only firearms with user-authenticated technology. Even gun control activists concede the mandate hurt adoption of the technology, and the bill's original sponsor is trying to get to it amended.

The threat of an NRA boycott looms large over this debate. In 2000, Smith & Wesson voluntarily adopted limits on magazines and said it would work to limit who gun dealers could have as customers. As part of a deal with the White House, the company also promised to pursue smart-gun technology. By October that year, after the NRA publicly bashed Smith & Wesson, its members boycotted the gun-maker, which was forced to lay off 125 employees. Months later, Saf-T-Hammer bought the company for $15 million cash and another $30 million in debt. Amy Hunter, a spokeswoman for the NRA's lobbying arm, says the organization wasn't behind the boycott, which "happened organically as a result of educating our members." She also says the NRA's opposition to the deal had nothing to with the smart-gun portion.

Today, there is still a vocal group that fears that user-authenticated weapons will lead to greater gun control. Which is at least partly why the only smart gun on the market has never taken off. The Armatix iP1, designed in 2006, has proved hard to sell. One California gun store was bullied into removing it from the shelves. A retailer in Rockville, Maryland, was threatened with arson. In a review, the NRA savaged the gun for its reliability. The iP1 also triggered fears of mandates and government plots. "What happens," a gun shop owner told USA Today, "if we put computer chips in all these guns, and Obama pushes a button, and all these guns go down?"

Another reason user-authenticated firearms haven't taken off: It's hard to quantify how many lives the technology could save. Smart-gun activists hope they could limit access to guns for suicides, which account for the majority of firearm deaths in the U.S. But Congress won't allow the CDC to do any research to "advocate or promote gun control," which greatly limits what the agency studies. In 2011, for instance, 102 children were accidentally killed by firearms, but it's currently impossible to know how many times kids were accidentally the shooters.

Despite the dearth of data, experts say smart guns would definitely deter people from using the roughly 200,000 firearms stolen every year. "Imagine," says San Francisco Police Chief Greg Suhr, "if you could brick a stolen gun like you can a stolen phone."

There are some signs there could be an emerging market for the weapons, at least among law enforcement. About 3.5 percent of the police officers killed in the line of duty from 2004 to 2013 were shot with their own weapon after it was stolen, according to the FBI. So when smart guns become as reliable as the standard-issue .40-caliber guns given to San Francisco police, Suhr says he'd be willing to offer the option to his officers. "I'm almost certain," he says, "that there would be some officers who would take it."

Kai Kloepfer, a preternaturally poised 18-year-old from Boulder, Colorado, is "the Mark Zuckerberg of guns," says Conway. Kloepfer thinks the smart guns of the late 1990s worked, but not well enough to get people to buy them, regardless of politics. In true Silicon Valley fashion, Kloepfer is hoping that advances in technology will force the entrenched gun industry to change, and it may have to be a startup that makes those advances. "Major gun manufacturers," Kloepfer says, "are not going to get anywhere near this."

Kloepfer is close to testing a smart gun that uses iPhone-like thumbprint technology, which he hopes will be completely reliable. And if we can now trust the lock on our iPhones, he argues, we can learn to trust a similar lock on our guns. Maybe, but earning that trust may take some time. After all, even Bond looked skeptical until his gun saved his life.

With Michele Gorman in New York.