In summer of 1982, photographer David Hanson was in the midst of an artistic crisis. He knew he could no longer take the kind of naturalistic landscape images Ansel Adams had made iconic: The American West that Hanson had come of age in during the 1960s was not the unspoiled wilderness Adams had captured but, rather, a landscape where nature was increasingly hemmed in by industry. "I was really calling into question the kind of work I'd done," Hanson says, speaking from his home in Fairfield, Iowa. "To make those pictures in the 1980s seemed very out of touch with the landscape we were living in and we were creating."

Confused, he decided to drive back from Providence, where he was on break from the graduate program at the Rhode Island School of Design, to his parents' house in Billings, Montana. On the way, he "stumbled across" Colstrip, a mining town in the plains of eastern Montana where industry, nature and human life coexist like three warring nations in a tenuous cease-fire. Taking wide-angle and aerial photographs, he captured a landscape ruined by humanity for humanity's sake: a silver trailer standing sadly in the middle of a barren field, smokestacks whose expulsions look like cotton candy against the chrome-colored sky, a neat suburban strip behind which churns the relentless machinery of American industry.

Hanson had found his subject, what the poet Wendell Berry calls "the monstrous ugliness" of the "irreparable landscapes" we have sacrificed in the name of eternal progress. Twenty-two prints from Hanson's Colstrip series were exhibited in 1986 at Manhattan's Museum of Modern Art, while a Guggenheim Fellowship allowed him to photograph about 70 Superfund sites around the nation. These, he says, are "the most enduring monuments America will have," nuclear and toxic grotesques that will linger long after our piddling and preening species has shuffled off this overheated stage.

This month brings Wilderness to Wasteland, a career retrospective of previously unpublished photographs that covers three decades of Hanson's work. The book is especially timely because while green thinking is on the ascent, green policies remain a liberal fantasy. Congress allowed the Superfund tax on energy and chemical companies to expire in 1995, thus vitiating the "trust fund" that paid for the cleanup of hundreds of polluted "orphan" sites on the National Priorities List (the official name for Superfund). These days, Ted Cruz, the Republican candidate for president, struts around the country railing against the Environmental Protection Agency, presumably because it is a leftist plague on average Americans. More credible people, too, have placed the National Priorities List low on the list of national priorities.

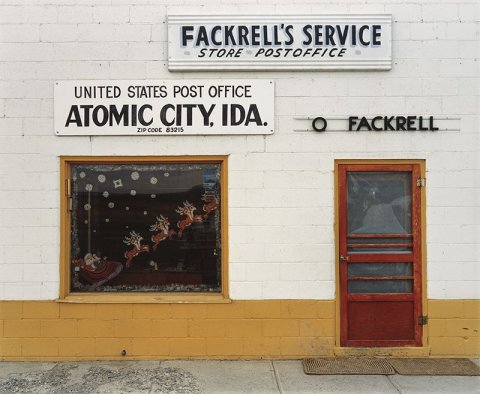

Wilderness to Wasteland is a testament to what we have done, and to what we must cease doing if all that talk of doing right by future generations is more than just political grandstanding. The photographs are beautiful but not pretty, evoking a landscape that is like a body riddled with ill-advised tattoos: car tracks across the desert floor in San Bernardino County, California; Atomic City, Idaho, where dreams of a nuclear energy utopia devolved into haunting desolation; the white silos of a Texaco compound in Rhode Island, the moon rising above them in a faint but indelible reminder of the tension between the world we inherited and the world we have made.

The book has Hanson traveling to some of the most infamous wastelands in America, including Times Beach, a Missouri town abandoned because of dioxin contamination, and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal outside of Denver, where the military manufactured and stored chemical weapons. The site was once deemed the most polluted place in the nation. Today, it is a park.

Hanson has always been comfortable with activism. In 1998, with the help of the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Mineral Policy Center, he gave a copy of his Waste Land: Meditations on a Ravaged Landscape to every member of Congress, holding meetings with many of them to discuss environmental legislation. He also worked with activists and politicians in Montana to pass a ban on a type of gold extraction that uses cyanide.

"The most damning evidence cannot be hidden from the intrepid aerial photographer," New York University sociologist Andrew Ross has written of Hanson's work, calling it a "stunning documentary of a century of organized state terrorism against the North American land, its species and its people."

Wilderness to Wasteland is being published as the nation grapples with the water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan. There are many Flints in the United States. Though lead is the culprit in Michigan, there are plenty of other culprits too, a guerrilla army of chemical killers we have unleashed upon ourselves. Sometimes the victims are the people, and sometimes the victim is the land. Too often, it is both.