Days before a Pennsylvania court planned to sentence him to years in prison in 1996 for molesting three children, Lynn Cozart—a middle-aged security guard—vanished. For years, investigators searched for him, but the case went cold—that is until 2015, when Pennsylvania state police sent Cozart's mug shot to a newly established unit of the FBI called Next Generation Identification (NGI).

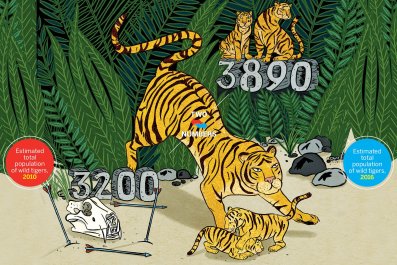

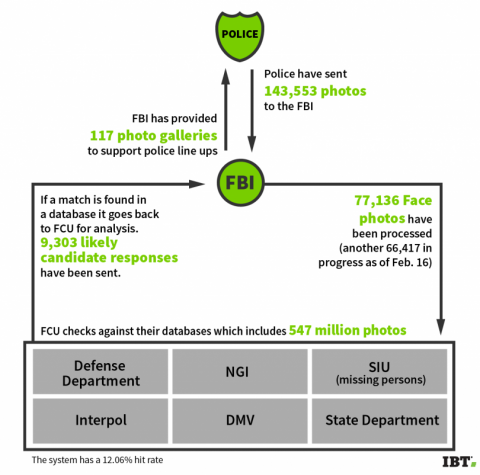

Fueled by fears of another 9/11-style attack, the bureau signed a $1 billion contract with military contractor Lockheed Martin to develop NGI in 2008. Three years later, the program began a trial period, and it officially began in late 2014. Today, the FBI's digital catalog of searchable "face photos" has ballooned to some 548 million pictures, the largest database of faces in history. It includes criminal mug shots; photos of suspected violent extremists overseas; and, thanks to an agreement with a number of state governments, driver's licenses and ID photos of Americans who have never committed a crime.

In his decade-plus on the run, Cozart had aged and changed his name. But his face couldn't lie. When the FBI ran its search, it matched a driver's license of a man named David Stone who lived in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and worked at a local Wal-Mart. Pennsylvania investigators alerted the FBI Violent Crimes Task Force. Within hours, the bureau arrested the notorious fugitive. The case, says FBI program analyst Doug Sprouse, is an example of how law enforcement is integrating facial recognition technology and other biometric methods to make the country safer. "After 19 years," he says, "[Cozart] was brought to justice."

Federal officials and law enforcement hail the NGI program as a futuristic way to track violence extremists and criminals. But others have been less enthusiastic. For all the brouhaha over the bureau's recent battle with Apple and encryption technology, many surveillance watchdogs and privacy advocates say biometric collection programs like the NGI are far more concerning when it comes to violating civil liberties. These critics say the FBI's biometric program is an extension of other sophisticated, modern-day military surveillance technologies—from drones used for aerial surveillance to StingRays, which intercept cellphone conversations.

"What we're seeing is how counterterrorism and counterinsurgency tactics are being codified into everyday policing," says Hamid Khan, a privacy advocate in Los Angeles and the founder of a grass-roots group called Stop LAPD Spying. "In essence, we're all suspects."

While facial recognition technology conjures images of a Minority Report–like control room, the reality is a bit more prosaic. No two people have the same fingerprints, and no two people have the same visage either. The FBI's technology measures minute distances in a person's face and logs the information. And while the bureau's biometric methods are still in their infancy, FBI officials say the program could help law enforcement locate and identify a suspect using surveillance videos, mug shots or even photos taken from Facebook and Twitter.

About a year after the NGI's official launch, the unit was growing so fast that it needed more space. So just after Christmas, the NGI moved to a larger facility, a 360,000-square-foot gleaming glass building located on 1,000 acres of highly secured land in the low mountains of Clarksburg, West Virginia. Security is tight. To enter, visitors must pass a federal background check. The campus even has its own police force, the third largest in the state. When the bureau granted me a rare look inside in February, Stephen Fischer, a 30-year FBI veteran, served as my escort. As we pulled up to the new building, he explained how it's intentionally housed on a secured property set back nearly 1 mile from the nearest highway, so "your average citizen has no idea what goes on here."

The FBI isn't the only agency that stores its biometric data in this facility. The Department of Defense, for instance, stores about 6 million photos of combatants overseas in rows upon rows of hard drives, which are stacked on individually marked tiles. If you've ever had a mug shot taken, your face exists on a hard drive in a room about the size of a professional soccer field.

The bureau's ultimate goal is to expand its long-established fingerprint system to include people's faces. So just as a detective would dust for prints at the scene of a crime, the FBI wants to offer police the ability to scan someone's face from a surveillance video and search that against a database. To do this, the bureau checks against its own database, but it also sends photos to participating state departments of motor vehicles. Depending on where you live, when you signed up to get your driver's license, the fine print may have authorized officials in your state to use your face to search against suspects in active investigations.

The FBI launched its biometric program in two states—Michigan and Arkansas—but 16 more have joined since. Sprouse, the FBI analyst, expects another half-dozen states to sign up by the end of 2016, adding millions more photos to the already massive repository.

The bureau maintains that it searches only against criminal databases, but its use of DMV photos is especially concerning for critics. Two of them, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Electronic Privacy Information Center—two of the U.S.'s most prominent privacy watchdogs—have filed lawsuits against the NGI to obtain records about the program. "I'm pretty sure when you went to get your driver's license," says Jeramie Scott, national security counsel for EPIC, "you weren't thinking that this picture...was now going to be used for large-scale facial recognition searches."

Scott fears biometric collection can quickly lead to the widespread invasion of privacy. In San Diego, for instance, some police carry around a mobile device that allows them to scan your face during an encounter, regardless of whether or not you are under arrest, he says. San Diego police, however, say the technology isn't used for data collection. "It matches against existing Sheriff's Department booking photos only," Lieutenant Scott Wahl, a San Diego police spokesman, told The San Diego Union-Tribune. "There is no DMV nexus, no FBI secret database. If you've never been arrested before, never been booked into county jail, your picture would never show up."

Scott's main concern, however, is what happens if facial recognition software gets it wrong. He says he's unaware of anyone who has been sent to jail because the NGI made a mistake, but in 2013 he filed a lawsuit to obtain internal documents about the program. He won, and what he discovered is that NGI is willing to accept a margin of error as high as 20 percent.

The FBI says its program is getting better, but facial recognition technology can, and has, made mistakes—with disturbing results. Consider the case of John Gass, a 46-year-old Boston truck driver who sued the city in 2011 after he received a letter saying the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles had revoked his license. His attorney, William Spallina, says the state DMV used anti-terrorism facial recognition technology. When it scanned Gass's face, the system came up with two names. Because the algorithm was configured to trigger a fraud alert when it returned two identical faces with separate names, the state said that, in itself, was evidence of fraud.

The result: The DMV revoked Gass's license, pending a hearing. Gass was out of work for two weeks and sued the city. Gass lost the case, but Spallina says it's scary that a glitch could cause so many problems. "It was absurd," he says. "You can't just do this without even a hearing."

The bureau says it takes privacy concerns seriously and contends that its facial recognition program has not (and will not) lead to false arrests. It says police officers or FBI agents would never throw someone in jail purely on information provided from this software. "No one's going to go out and knock on a door and make an arrest based on the information we provide," says Sprouse. "There has to be supported information."

Stephen Morris, an FBI veteran who oversees the NGI unit, agrees. "Everything we do here, we do it with privacy in mind," he says. And when the bureau uses biometrics, he adds, "the level of certainty that we have the right person goes up exponentially."

That's what happened in the Cozart case, but when I asked the FBI to provide me with other examples of using facial recognition to locate a violent extremist or criminal, the bureau couldn't provide one. Which is perhaps why watchdogs like Khan say the FBI's NGI program is another example of the federal government investing in technology that—while intended to help law enforcement—winds up becoming an expensive and questionably effective form of Orwellian surveillance.

"With all these tools, there's an information overload," Khan says. "Our money is going towards these things—the surveillance industrial complex." And the budget for such programs, he adds, is "infinity—because there's no end to the war on terror."