On a recent afternoon in Lashkar Gah, the capital of Afghanistan's Helmand province, the Emergency Surgical Hospital for war victims was unusually quiet. After a busy week, with spring temperatures pushing 115 degrees, the staff looked hollowed-eyed with exhaustion. Three of the hospital's young foreign nurses—Chiara Lodi and Pamela Puccio, Italian women, and Ciaran Dunleavy, a bespectacled Brit—checked on patients, then retreated to paperwork with strong coffee and cigarettes. There was talk of leaving early.

But that didn't last long. Four new patients, Afghan soldiers from nearby Marjah, were raced into the emergency room. Their truck had rolled over a land mine. One, with bloodied legs tourniqueted at the thigh, was already dead. Another, apparently uninjured, crouched on the floor of the emergency room, his head in his hands in shock. The other two, legs and arms pockmarked by shrapnel, sat up and silently stared at their colleague's corpse as nurses cleaned their wounds.

On the count of three, hospital assistants lifted the dead soldier from a gurney, wrapped him in opaque plastic and transferred him to the morgue, leaving behind a blood-soaked mattress.

One of the hospital's administrators, Massimo Malandra, an unassuming Italian in his 40s, stopped briefly to examine the mess. "Helmand," he said darkly, before moving on.

Emergency, an international nongovernmental organization, was founded in Afghanistan in 1999 by the war surgeon Dr. Gino Strada, a divisive figure in his native Italy for his vehemently anti-war views. It has a simple mandate: to provide free, first-class health care to war victims, regardless of who they are.

As the center of Afghanistan's lucrative opium trade, Helmand has long been the country's most violent province. It is where nearly 1,000 international troops have died since 2001. Today, 18 months after the withdrawal of most international troops, it has deteriorated so much that the Taliban now control or contest all but three of 14 districts in the province.

Nowhere is the continued violence more evident than at Emergency's hospital in Lashkar Gah.

In one ward, Guldana, a baby girl, lay serious and silent, with bandages covering bullet wounds to her head and tiny legs. Shahguda, a 30-year-old woman, four months pregnant, was recovering from surgery after a misfired mortar ripped off her arm. Arifullah, a police officer, accompanied by wild-eyed colleagues who said they hadn't eaten for three days, repeatedly screamed "my leg" as he was wheeled into the emergency room. An improvised explosive device had blown off his left foot.

As I ate lunch with members of the staff during my visit, they looked dejected. A tiny 10-year-old boy, who arrived weeks before in critical condition, had just died. "I hadn't seen a dead child until last week," said Dunleavy, who recently arrived in Helmand, after spending most of his nursing career in Sydney. "Now I've seen a few."

Up to 50,000 civilians, government forces and Taliban are thought to have been killed or injured in Afghanistan last year. It is a staggering figure, but still an "enormous underestimation…and everybody knows it," according to Luca Radaelli, Emergency's program coordinator in Afghanistan.

This year is expected to be worse, and Emergency in Lashkar Gah is expanding from 90 to 103 beds to meet the demand.

In places like Lashkar Gah, which has no high-quality government medical facilities, Emergency is one of very few options. Afghanistan's public health system is in a terrible state, despite the injection of development aid to the country exceeding well over $100 billion. Emergency runs three free hospitals, as well as 46 first-aid posts and clinics, and employs more than 1,500 staff in Afghanistan for $10 million annually, funded by donations and grants (though not from parties involved in the conflict). Its Helmand operations cost approximately $2 million a year, roughly the cost of keeping one U.S. soldier in Afghanistan for a year.

Emergency has continued its work despite a slew of attacks on health facilities in war zones, including Yemen and Syria. This past October, a U.S. airstrike on the Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, northern Afghanistan, killed 42 people, including medical staff and children.

While the U.S. has apologized, Afghan officials have largely refused to disavow the attack. A recent investigation by The New York Times Magazine suggests the Afghan military may have directed U.S. forces to strike the hospital in the belief it was a Taliban hideout. Attacks on other health facilities in the country, including a raid by Afghan special forces on a Swedish Committee for Afghanistan clinic in February, have also gone unexplained.

The Emergency staff in Lashkar Gah all insist the Kunduz airstrike has not spooked them, but their head office insisted they build a steel-reinforced bunker at the hospital. In late May, as the U.S. continued bombing raids in Helmand, the head of the provincial council warned that Lashkar Gah could fall to the Taliban.

Emergency officials say they have no evacuation plan, and as a neutral NGO, they will continue offering health care to everyone. It is a position they often have to explain to outsiders. "It makes me crazy that many people question us why we treat the Taliban," says Radaelli. "In Italy, I treated criminals, Mafia, junkies, drug dealers—nobody asked me why I did that. My job is to treat human beings."

In 2013, a failed suicide bomber, whose vest only partially detonated, was brought to the hospital. The Afghan surgeons and nurses, whose families live in the city the suicide bomber targeted, were furious. But they treated him. "That's my role as a doctor," says Dr. Shahwali Alizay, one of Emergency's senior surgeons.

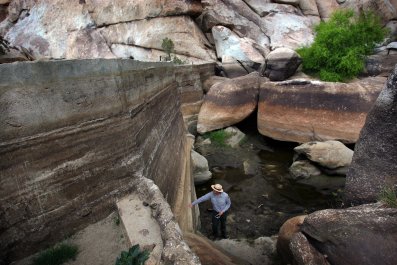

The horrors of the hospital represent just one side of this provincial capital. Lashkar Gah in late spring can appear idyllic. Helmand's eponymous river cuts a wide, flowing path through the small capital. In the late afternoon heat, as mothers shop at the nearby bazaar in mint green and lilac burqas, young boys discard their sherbet-colored shirts, known as shalwar kameez, to swim in the river.

Despite the fact that the hospital is only about a mile away from the river, only one member of the international staff has seen it. Strict security rules mean that they divide their time between the hospital and their shared, modest guesthouse. (A few years ago, Vesna Nestovoric, the Helmand medical coordinator, then stationed in Panjshir, was allowed to visit a regional clinic—an experience so rare that she still talks about it.)

Twice a day, all eight staffers cram into two white-and-red four-wheel-drive cars. In Afghanistan, criminal gangs regularly kidnap foreigners, Western NGOs are terrorist targets, and foreigners in general draw hard stares and curious attention. But no one in Lashkar Gah seems to glance twice at the Emergency cars.

Emergency has not always felt so welcome. In 2010, three Italian and six Afghan staff were arrested, accused by Helmand's then-governor of plotting to assassinate him, after suicide vests and weapons were planted in the hospital. In the media fallout, the governor also accused Emergency of unnecessary amputations on Afghan soldiers, implying they were supporting the Taliban.

Strada denounced the arrests as a ploy to force the organization out of Helmand. Emergency will say little of the 2010 incident today. "Somebody was not happy about our presence [in Helmand]," as Radaelli puts it. "The important point is that we were proved innocent...and today we have a very good relationship with the Afghan government."

When I first visited Emergency's hospital in Lashkar Gah, I was struck by the spotless facilities, a rarity in Afghanistan, the sunflower-filled courtyards and how some Afghan staff spoke English with Italian accents. But most of all, I was struck by the commitment of the international staff, who support and mentor an equally committed Afghan cadre.

Leonardo Radicchi, a former professional jazz saxophonist, is the hospital's manager of logistics. On his hip is a radio, which all the foreign staff carry with them at all times, that crackles constantly, announcing new patients. It wakes them up at night.

Recently, Radicchi was struck down with malaria and decided to take a day off work to recover. But a suicide bomber attacked a police building, and when he heard the radio announcement that 13 patients had arrived at the hospital, he got up and went to work.

Most of the staff say they came to Afghanistan—or other places where they have worked for Emergency, such as Libya, Kurdistan and Somalia—out of a nagging feeling that there was more to life than a career in a Western hospital. One day, after more than a decade working at a hospital in New York, Dr. Joseph Rumley, an Irish anesthetist, says he looked around and thought, "Fuck, am I really going to do this for the next 20 years?"

While they may have found a purpose in Afghanistan, nobody at Emergency romanticizes war. "We have this romantic way to describe war, because we're used to TV, movies, video games," says Radaelli. People who get shot in a war movie "die from one bullet peacefully, like a hero. It's bullshit." Chiara Lodi, an Italian with lavender-dyed hair, tattoos and a tongue piercing, had a similarly blunt assessment. "This war is stupid," she says. "[Afghans] are growing up learning that to solve conflict, they have to fight. Because of that, I'm here."