The debate over urban graffiti is a complex one, frequently pitting commercial interests against artistic ones. Graffiti in the wilderness is a much simpler matter: It is a despicable crime, never more so than when the tags mar national parks. That is the takeaway from the case of 23-year-old Casey Nocket, also known as "Creepytings," who this week pleaded guilty to defacing government property by applying her images and tag to seven national parks in the West during a dismayingly productive 2014 trip. So prolific was Nocket during her 26-day adventure, that in two parks, Crater Lake and Death Valley, her masterpieces have not yet been removed.

I first learned about Nocket in the Mojave Desert, from activists and explorers who deeply valued the alien landscapes and vast expanses of places like Death Valley and Joshua Tree. As activists tend to, they complained: about greedy speculators, witless politicians, real estate developers—and graffiti artists who, apparently tired of warehouse walls, were heading out into the desert.

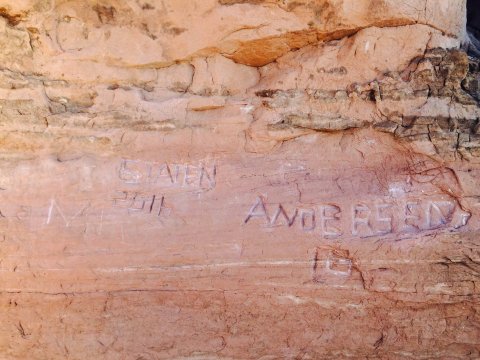

The blog Modern Hiker had first alerted the world about Nocket's work in 2014. In an October 21, 2014, post, Modern Hiker's Casey Schreiner reported that Nocket "was so moved by all the natural beauty she saw that she just had to paint all over it." Her calling card—usually, a stylized portrait, with her "Creepytings" tag—appeared in some of the most famous parks in the West, including the Grand Canyon, Yosemite and Zion. Her weapons were acrylic paint and marker. And she incautiously recorded her exploits on Instagram and Tumblr.

Sensing unwanted attention, Nocket quickly locked her Instagram account; yet she apparently defended herself on Tumblr, where she is said to have responded to one critic, "If banksy did it u'd have a hardon," an allusion to the mysterious British graffiti artist whose work is widely celebrated. The infrequently circumspect site Gawker called Nocket a "terrible human," echoing what appeared to be prevalent sentiment.

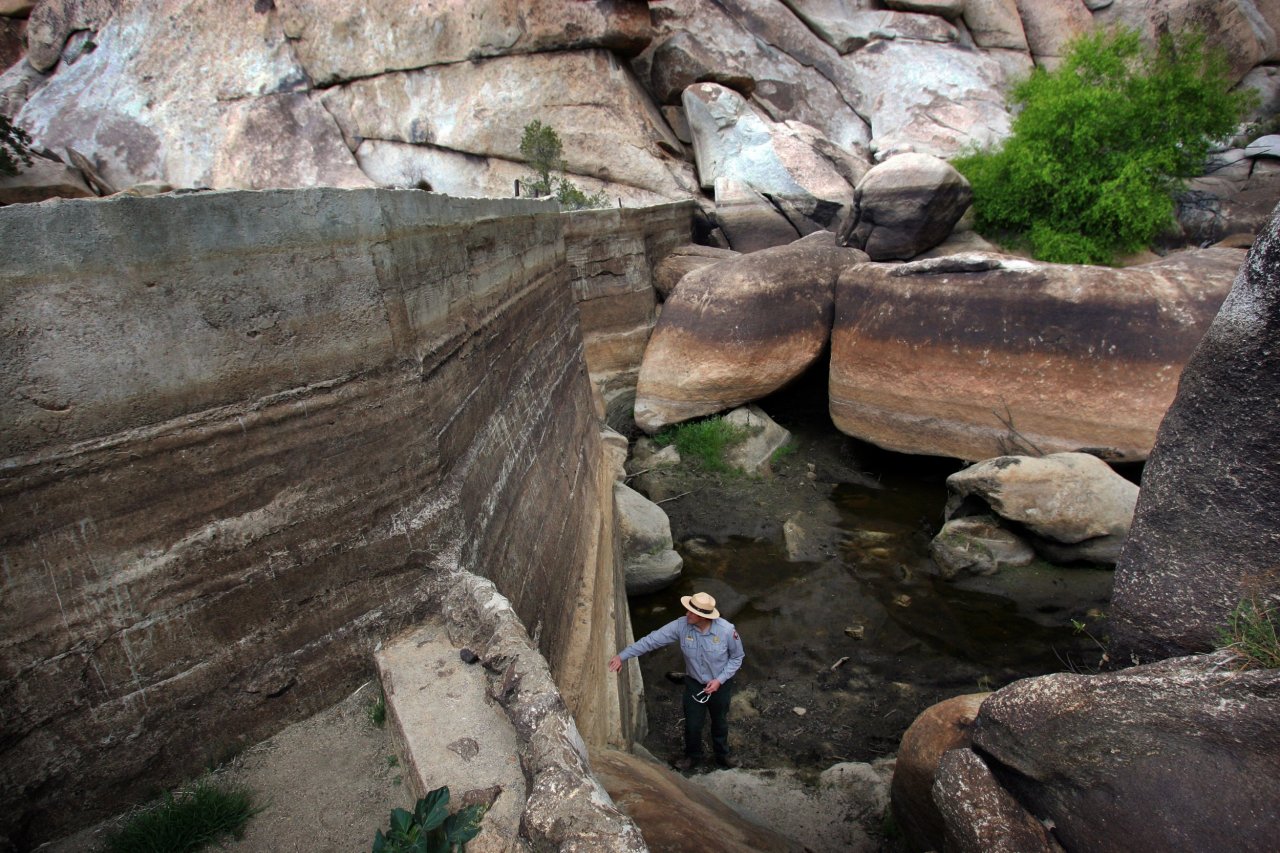

The National Park Service successfully identified her as the culprit and launched an investigation that concluded with Nocket appearing in federal court in Fresno, California, on Monday (her agreeing to appear in court obviated the need for an arrest, a Department of Justice spokeswoman tells me). According to the San Diego Union-Tribune, she will be on probation for two years and must perform 200 hours of community service. In addition, Nocket "was banned from entering any national park while serving her sentence and will be required to pay restitution."

Nocket was the target of plenty of outrage, but she is merely a convenient symbol for an entire criminal subculture that takes pride in the vandalism of national parks, particularly in the West, where the desert is some of the last truly American wilderness that remains. Much of the protected land is sacred to Native Americans too.

This seems to matter little to those whose vulgar narcissism is worthy of Donald Trump. In April, Arches National Park in Utah was defaced with graffiti "that was carved so deeply into a famous red rock arch that it might be impossible to erase," according to an Associated Press report. Two months before that, alleged celebrity Vanessa Hudgens faced a fine of $5,000 for defacing a rock in Arizona's Coconino National Forest. Such incidents have become disturbingly common, with vandals celebrating their exploits on social media, in seeming ignorance that they spoil the experience of wilderness for the rest of us.

"National parks are special places for most Americans. Seeing them marked up is like getting punched in the gut," Schreiner told the Los Angeles Times last year. At least the vandals' online indiscretion makes them easier to catch.

There is a wholesale argument about the criminality of graffiti that deserves skepticism: The works of Banksy and Swoon are very much art, and that they appear on the side of a building only enhances their message and allure. But if such work appears on a rock formation in Death Valley, that's simply a crime, whether you are the next Kandinsky or not.