There's a good chance you've heard of Nate Silver. After getting his B.A. in economics at the University of Chicago in 2000, Silver took a job as an economic consultant with KPMG, the consulting company, but quit after a couple of years and made good money playing online poker. He also came up with a widely applauded method for forecasting the performance of Major League Baseball players. His mathematical model, dubbed PECOTA ( Player Empirical Comparison and Optimization Test Algorithm), made him a Moneyball-style legend.

Because Silver's father is a political scientist, it seemed natural that the bespectacled statistician would turn these Freakonomics-like sensibilities to elections, using the same data analysis that brought him success in baseball. In the 2008 presidential election, he called the winner in 49 states, and he went 50 for 50 in 2012. His work earned him nerd celebrity, TED Talks and a New York Times blog that has since migrated to a website under the ESPN umbrella. Its name—FiveThirtyEight.com—comes from the number of Electoral College votes necessary to win the presidency.

In early July, Silver and the folks at FiveThirtyEight concluded that Democrat Hillary Clinton stood an 80 percent chance of being elected president in 2016. The predictions are based on a gumbo of current polls, weighted by their reliability, as well as economic conditions and other predictors of voting behavior that will change over the next four months.

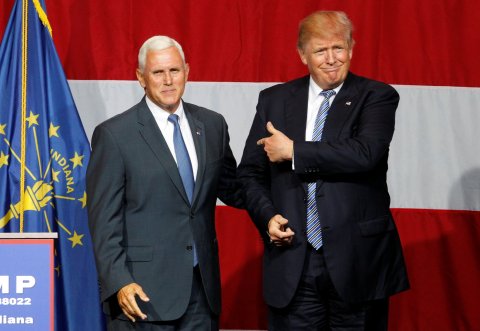

But it's worth noting that Silver and his team were way off about Donald Trump's odds of securing the Republican nomination. In a December post headlined "Dear Media, Stop Freaking Out About Donald Trump's Polls," they rated Trump's chances of getting the nomination at less than 20 percent. Silver's oft-repeated, data-driven underestimation of Trump—which was echoed by most, but not all, of the data-averse punditocracy—is a reminder that the mogul's prospects might just be better than is commonly thought.

To understand why Trump has a shot, it's important to be aware of the limits of polling, a profession that has been going through an intense bit of self-examination thanks to the changing landscape. People these days aren't using landlines as much, they're ignoring calls when they don't recognize the number, and they're more reluctant to chat with a stranger about their politics. All this has forced the survey industry to keep reassessing how it takes the public temperature.

In the aggregate, polls have been pretty much correct this year—but they're wrong often, and sometimes spectacularly, enough that one should be wary about predicting Trump's demise. In the recent U.K. referendum, polls predicted a close vote on the question of whether to leave the European Union, known as Brexit. But they generally concluded the Remain side would win. As we all know, the Leave side scored a narrow victory.

Similarly, polls in the U.S. correctly picked Trump as the most popular Republican in the primary field and called his victories in individual states rather well. But individual polls can be fluky and weird. ( For example, surveys in the Michigan Democratic contest vastly underestimated Bernie Sanders's strength because they oversampled older voters who favor Hillary Clinton.)

If you're a consumer of polls, it makes sense to look at a few of them and discard the outliers. In general, polls on the eve of the Republican National Convention show Clinton leading Trump by about 4 percent overall. But even if Clinton's lead is 8 percent or 10 percent, as some polls have it, that's a closable gap. It's worth noting that a July 1988 Newsweek poll had Michael Dukakis leading George H.W. Bush by 17 percent—a survey that became famous (or infamous) because the election turned out so differently. Other, more accurate polls were closer to 10 percent, but Bush closed the gap regardless—and he didn't carry Trump's massive baggage. Bush's comeback is a reminder that autumn surges are possible. (Jimmy Carter was ahead by more than 33 percent after his Democratic nomination in 1976 but won by only a narrow margin in November.)

It's become almost conventional wisdom that Trump is doomed because of America's changing population. The country is famously becoming more Hispanic, a demographic he seems to relish infuriating. Trump's pugilistic approach to Hispanic issues is remarkable: He's called for building a wall with Mexico, demanding that the Mexican government pay for it; deporting an estimated 11 million immigrants without documentation; and ending the 14th Amendment's guarantee of citizenship for those born on U.S. soil. His May 5 tweet celebrating the Mexican holiday Cinco de Mayo—featuring a photo of him chowing down on a Taco Bowl from Trump Grill—didn't help.

Meanwhile, the pool of white voters—where Trump must look for the overwhelming majority of his votes—is shrinking. In 1980, Ronald Reagan won a general election landslide with 56 percent of the white vote; by 2012, Mitt Romney would lose decisively with 59 percent of the white vote. What had changed in the intervening years was the surge in the Hispanic population. Romney won 27 percent of Hispanic voters , and Trump often polls around 20 percent or lower.

And yet, while it might look like a walk to the gallows, this isn't necessarily a death sentence for Trump's campaign. Most Hispanic growth is concentrated in a few states, including California and New York, which Trump is all but guaranteed to lose regardless of the Hispanic vote, and Texas, where he is almost certain to win. Swing states with booming Hispanic populations, such as Nevada, Colorado and Florida, are tougher for him but remain toss-ups. In Florida, the largest swing state, Hispanics constitute 18.6 percent of the electorate thanks to an influx of Democratic-leaning Puerto Rican citizens. Trump is going to have a struggle.

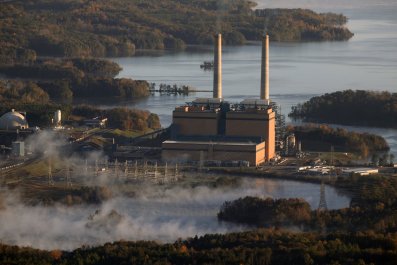

But here's his possible salvation: The Rust Belt states have low Hispanic populations and high percentages of working-class white voters, the core of Trump's base.

Nationally, Hispanics are expected to constitute 11.3 percent of eligible voters in the 2016 election, compared with 10 percent four years ago. That's lower than their overall 17 percent of the U.S. population, because Hispanics skew younger and are less likely to be citizens. In Ohio, arguably the most contested swing state, Hispanics constitute only 2.3 percent of the eligible electorate, ranking it 42nd in the nation. (New Mexico, where that number is 40 percent, tops the list.) In hotly contested Wisconsin, the Hispanic share of the electorate is just 3.6 percent, and in Iowa it's 2.9 percent. So Trump can get by without much Hispanic support in the Rust Belt because his electoral core—white voters who have some or no college in their background—constitute big percentages of the electorate there.

Romney lost those states by modest amounts, but Trump has some things going for him that Romney did not. The private equity billionaire opposed the auto bailouts that greatly benefited this area of the country, and he made his famous derogatory crack about 47 percent of Americans being takers, something that was unlikely to lure working-class voters already being bombarded by ads portraying Romney as a plutocrat. By opposing international trade deals and vowing to protect Social Security from any cuts, Trump may have more working-class appeal in the Rust Belt than the CEO-friendly Romney did. (It's true that Romney was, like Trump, an opponent of path-to-citizenship-style immigration reform, but he was less outspoken about it.)

Another big factor that could help Trump is turnout—which groups actually show up at the polls. In 2012, Romney's forces didn't think minority turnout would match the 2008 "hope and change" surge that helped make Barack Obama the first African-American president. They were wrong, and Romney got clobbered. But can Clinton match Obama's enthusiasm among minority voters? And can she do as well with young voters? Voters ages 18 to 29 went for Sanders overwhelmingly in the Democratic primaries, but they oppose Trump. Modest changes in this kind of "modeling," as the pollsters call it, can make a big difference. David Wasserman, a political analyst with the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, came up with a "Swing-O-Matic" showing how such small changes can make a huge difference.

The other big X factor that could help Trump is that both he and Clinton are so widely disliked, with record-high unfavorables in polls. With these kinds of negatives, you can't be sure whether any of the traditional "modeling" about who is likely to show up at the polls is valid. And all those high-tech efforts at microtargeting—like trying to determine if a voter is persuadable by his or her consumer preferences—that have been largely eschewed by Trump (but were a big key to Obama's presidential victories) can be harder to employ when there's such a big "ick" factor. In the universe of primary voters, Trump and Clinton didn't carry such high negatives. Now that they're swimming in the big pool, facing the widespread view that they're liars, or at least dishonest, it makes for a crazed race. "Both parties managed to pick the person voters are least receptive to hearing," says David Winston, a veteran Republican pollster. "Voters are likely to bounce around because they have an unfavorable view of both."

Pity the statistician in this environment. In 2012, Silver wrote a book, The Signal and the Noise, a cautionary tale on why some predictions tend to be quite accurate (where a hurricane will land) or way off (where the next earthquake will strike). It's a reminder of another book, The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, which takes its title from how scientists believed all swans were white until they came upon a black one. Failures of science and imagination blind us to the possible. That seems fitting these days. Trump has a chance to be our orange swan, a political creature no one ever imagined who could land in the White House.