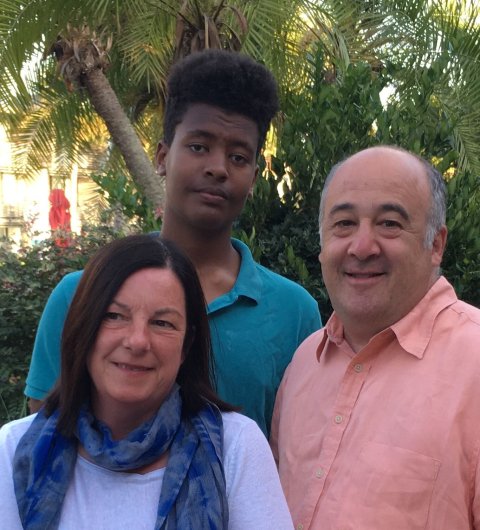

Updated | In August 2014, while vacationing with his wife and son in Puerto Rico, Ken Deutsch felt a sharp pain along his spine. He'd had backaches before, but this was new and more severe. He began popping Advil "like crazy," he says, then noticed another symptom: blood in his urine.

It wasn't the first time he'd seen it. It had shown up in April. He had an enlarged prostate, so his doctor thought it might be a related infection. But when antibiotics didn't stop the blood, he went to a urologist. After a scan and a scope, he was eventually diagnosed with Stage I bladder cancer. The doctor had found multiple tumors on the inside of the sac.

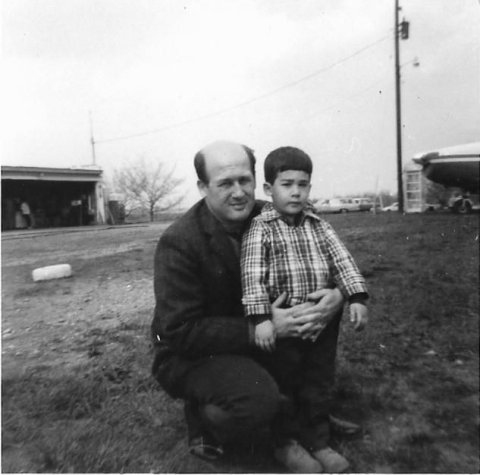

There's been a lot of cancer in Deutsch's family. His father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at age 52 and died within months. His grandmother had pancreatic cancer too, but her death was slow, agonizing. "I was like, Whew, I dodged a bullet. It's only bladder cancer and Stage I," says Deutsch. "We caught it early. We can get it under control."

Around the same time he received his diagnosis, Deutsch, then 52, read a blog post that a relative had shared on Facebook. It was about one of his second cousins, who had just passed away from ovarian cancer. As the post noted, she had a mutation to her BRCA1 gene; variants of the gene are known to significantly increase a woman's risk for breast and ovarian cancer. While less definitive, a growing body of research also links BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to heredity risk for other cancer types. (One study published online in MedGenMed suggests the BRCA pathway is associated with a 20 to 60 percent greater risk for cancers of the stomach, pancreas, prostate and colon.)

After hearing about his family history, Deutsch's doctors ordered a diagnostic screening test for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations made by Myriad Genetics and used to evaluate the risk for breast and ovarian cancer. (The company helped discover the genes in the early 1990s.) The test showed he has the same mutation as his second cousin—an extremely rare variation of the BRCA1 gene. There's nothing in scientific literature definitively linking any BRCA mutations to bladder cancer, although there is evidence that people who carry one respond better to certain types of chemotherapy.

Having a mutation that might be only in his family feels akin to having a "rare disease," Deutsch says, so he was frustrated to learn that Myriad doesn't share its data. For all he knows, the company is sitting on the files of 30 other people who have his mutation and have bladder cancer, which would point to a link between the two. At the moment, his genetics don't explain his illness.

Frustrated, Deutsch became involved in a new complaint that pits one of the biggest names in genetics against an at-risk group it's supposed to be helping. On May 19, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed the complaint against Myriad to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), accusing the Utah-based company of failing to release data from its analyses even after patients requested it, a violation of their rights under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

The filing with the HHS comes amid what experts are calling a new era in cancer research, in which shared data could speed up innovations and therapies for patients. To everyone it tests, Myriad reports mutations that are known to affect cancer risk. Those involved in the complaint subsequently asked for their full genetic workup, including BRCA variations currently considered to be clinically insignificant. Knowing it, patients argue, could help them monitor their cancer risk because previously seen mutations, like Deutsch's, might be potentially linked to tumor growth. They also want the ability to donate tissue samples to one of several repositories that could potentially benefit cancer research. However, Myriad initially balked at returning the additional information.

"Their only defense," Deutsch says, "is that they're trying to hold data about individuals as...proprietary...so that they can make more money."

A Monopoly on Patient Data

This isn't the first time the ACLU has taken on Myriad. In May 2009, the group represented cancer patients, advocacy organizations and others in a suit against the company's patenting of the BRCA genes. After a protracted legal battle, the Supreme Court in June 2013 unanimously ruled that naturally occurring DNA could not be patented.

The patents, among other things, had allowed Myriad to be the sole entity that offered clinical diagnostic testing for those genes, says Tania Simoncelli, a former ACLU science adviser. The high court decision permitted competition and caused Myriad's stock to plunge nearly 25 percent. "Myriad's temporary monopoly allowed it to amass an enormous proprietary database," Simoncelli tells Newsweek via email. "Since the mid-2000s, Myriad has not shared its data with public databases."

Simoncelli and others interviewed for this story note that a new paradigm for cancer research is emerging that allows patients to participate in the study of the disease by sharing their data with scientists, medical centers and biotechs to speed the development of diagnoses and therapies. Among those who have signed on to the effort: the Obama administration. Earlier this year, the White House launched a program called Cancer Moonshot. It's headed by Vice President Joe Biden, who lost his oldest son, Beau, to brain cancer in May 2015. Its goal, as Biden put it earlier this year, is "to break down silos that keep research away from the world and from one another." As part of the effort, scientists, universities, grassroots organizations and institutions like the National Cancer Institute have pledged to build portals to quickly and widely disseminate data on genetic tests, treatment responses, personal experiences and more.

But as the case of Myriad indicates, sharing can sometimes be complicated. In February, Ron Rogers, the company's executive vice president of corporate communication, says Myriad received seven identical letters from patients. They were "written by a lawyer," he adds, asking for all mutations identified as part of the analysis of their BRCA genes. When the company sent only standard test results and said patients were not entitled to any further data, the ACLU drafted its complaint saying the company was violating HIPAA's Privacy Rule. It specifically pointed to a legal requirement that grants patients access to "underlying information generated as part of [a laboratory] test," if they request it. In this case, the records should include variations in their genes that are currently considered benign.

The HHS had advised genetic labs of this responsibility in February 2014, but it wasn't until Myriad received the requests about two years later, Rogers says, that the company realized the guidance had been issued. He says he and other representatives from Myriad then flew from Salt Lake City to Washington, D.C., in April to meet with employees of the HHS's Office for Civil Rights to determine what they were required to do.

The company eventually turned over more information on May 18, one day before the ACLU filed its complaint. According to Rogers, it was a coincidence that the data arrived just before the filing. "We had been working on it for weeks, and as soon as it was ready, we sent it to them."

While the HHS is still considering the ACLU's complaint, Rogers says Myriad considers the case closed. He also disputes accusations that his company doesn't share data, noting that it prefers to disseminate its findings via peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Nevertheless, according to senior staff attorney Sandra Park, the ACLU decided to push forward and alleges that Myriad's policy continues to deny this secondary information to patients—and that the company still operates in violation of HIPAA. Among other things, the complaint claims the data should have been turned over in a machine-readable format, so it could be easily uploaded to various national databases. Instead, in the case of Deutsch, Myriad emailed him a 20-plus-page PDF filled with charts and graphs.

"They requested information, we provided it to them, and they're free to do whatever they want to with it," says Rogers. "If they want to enter it into a database, they're free to do that. Someone can hand-enter it in if they really wanted to."

Lone Survivors

Not long after Deutsch called his urologist from Puerto Rico, he was brought in for a transurethral resection of bladder tumor, the standard outpatient surgery for his condition. He'd already had the procedure after his original diagnosis, but because bladder cancer often recurs, the doctors went in again. In October 2014, as Deutsch was about to be anesthetized, his doctor burst into the pre-operating room; he'd found several new tumors on a positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

The cancer had spread to Deutsch's bones, which explained his back pain. And it wasn't Stage I anymore. It was Stage IV, the most severe type.

The doctor referred Deutsch to the nearby Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, one of the world's pre-eminent cancer centers. Once there, he immediately started a platinum-based chemotherapy treatment; people who have BRCA mutations tend to respond to it better than other forms of chemo.

Deutsch says knowing his genetic background helped him feel optimistic, even when chemo left him weakened and ill. "I'm probably the only person you'll ever speak to who's glad that I'm BRCA1-positive."

Today, he shows no evidence of disease, and he's become an amateur genealogist of sorts. After finding out his BRCA status, he reached out to his cousin Barbara Zeughauser, who has never had cancer but has tested positive for the same rare mutation. (She's also a named party on the ACLU complaint.) Zeughauser and Deutsch both lost parents and their mutual grandmother to cancer.

Because of the prevalence of the disease in their family, the cousins started collecting phone numbers and Facebook profiles of family members and contacting relatives to see if others had had genetic testing. "We know seven of us who are alive, including my cousin Barbara, who are BRCA1-positive for the specific mutation," says Deutsch. "We know of eight additional people who have died that, based on who has the specific variant, it's pretty much assured that they had the variant."

Deutsch and Zeughauser, with the help of their siblings, have mapped out 25 relatives who have had cancer—just on Deutsch's father's side. Of the seven people they know who are living with the rare BRCA1 mutation, only two, including Deutsch, have been diagnosed with cancer. For those who are currently cancer-free, the information can help them make decisions about their health, from getting more frequent screening to opting for preventive mastectomies or having their ovaries removed.

But Deutsch can't help but wonder if the mutation he and his family members share exists beyond his bloodline. If you search for his mutation in public databases, such as the Genetic Mutation Database assembled by the nonprofit Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered, you'll find just two entries. One is him. The other is his second cousin, the sister of the one who died.

"We know that some BRCA1 or 2 variants are more likely to cause cancer than others," Deutsch says. "Which cancers which ones cause, there's not enough data to reliably be able to pinpoint that information. We don't know much about it," he adds, "because [Myriad is] holding on to the data."

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly stated that the Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered database doesn't list contact information, but it does. It also incorrectly stated that the only people with Deutsch's mutation listed in the database were him and his second cousin, who had died of ovarian cancer.