A version of this story first appeared on Medium

Just eight weeks after Pearl Harbor, John McCloy, then the assistant Secretary of War, sat in the Oval Office with his boss, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and the president, Franklin Roosevelt. America had declared war against Japan. There were reports that Japanese submarines were lurking off American coasts. Dense fear hung low over the country, clouding the senses. In that moment, FDR informed McCloy the U.S was going to intern Japanese-Americans. The president told McCloy he expected him to oversee the process. It was good for the country, FDR believed; America couldn't risk another attack. And with a tone that underscored his personal fears, FDR said to his aide: "We don't want another Black Tom Island."

McCloy knew exactly what FDR meant.

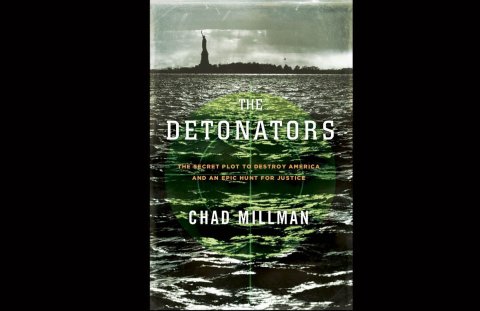

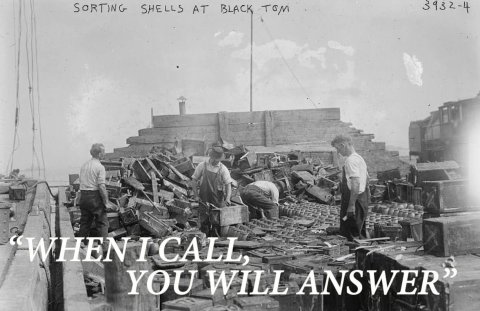

Prior to World War I, Black Tom Island had been the largest munitions depot in the country, from which American-made shells, detonators and bombs were shipped to the British and the French. One hundred years ago this summer, German saboteurs destroyed it. The explosion shot columns of fire into the sky, leveled much of downtown Manhattan and sent tremors reverberating as far south as Maryland, as I reveal in my book, The Detonators, which covers the attack on Black Tom, and the subsequent investigation.

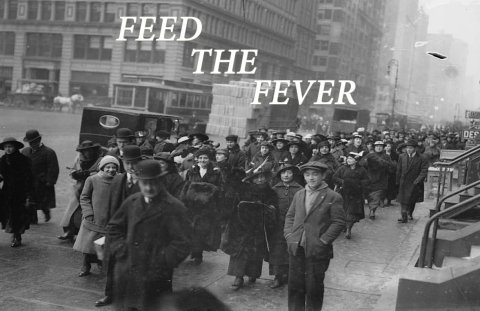

FDR's comments to McCloy emphasized what Americans were feeling in that winter of 1942, which tied directly to what Americans were feeling in the summer of 1916 (and, in many cases, what they feel today). Mistrust, anger and discontent all combined to create a stew of anxiety focused on first- and second-generation immigrants. In 1942 it was Japanese-Americans. In 1916, it was German-Americans. Newspapers that year reported that German-Americans were ready to attack metropolitan areas from within as soon as the U.S. entered the war. Fears of a Kaiser-led army from within were so pronounced that the Met in New York stopped performing German-language operas. Sauerkraut was renamed "liberty cabbage." Teddy Roosevelt barnstormed the country railing against "hyphenated-Americans."

McCloy had been a college student that summer of 1916. He had been in the crowd for one of Teddy Roosevelt's speeches, believing every word, and he had then served on the front lines in France during World War I. Later, as a young lawyer, he took on the Black Tom Island case, spending more than a decade investigating how German spies had operated in the U.S. prior to the war, how they had plotted to, and succeeded in, blowing up New York Harbor.

It was that understanding that earned him a job working for Stimson, who wanted someone who he believed understood the mindset of the German government. All of that swirled in McCloy's head as Roosevelt told him to intern the Japanese, as the president reiterated his fears of another Black Tom Island.

This excerpt below—inspired by The Detonators and reimagined in storyboard form—is why they both were so afraid.

July, 1916, New York City

Frederick Hinsch, a rotund German, arrives at the Hotel McAlpin on 34th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. In the lobby, Michael Kristoff, a gaunt and gray-skinned Austrian immigrant, perks up as Hinsch arrives. Hinsch, however, barely acknowledges Kristoff's existence. Instead he bullies his way through the crowd. Kristoff drops his head and follows.

In his hotel room, Hinsch hands Kristoff $500. "Remember those suitcases, Michael?"

Hinsch's voice rumbles from deep within his massive belly. But Kristoff is fixated on the money.

Hinsch continues, snapping his fingers. This man is a simpleton, he remembers.

"Michael, the last time we were together, I asked you to watch those suitcases for me. Do you remember?"

Kristoff lifts his head, making eye contact with Hinsch. A connection. Kristoff nods his head yes.

"And you looked inside?"

"I did," Kristoff says.

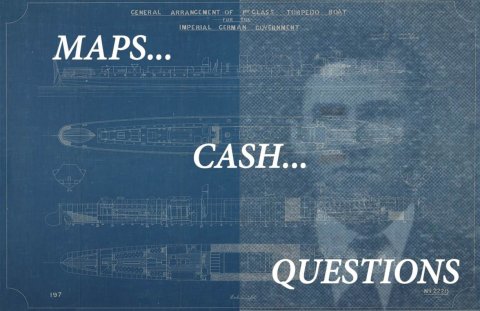

"You saw those maps and those blueprints?" Hinsch asks.

"And the explosives," Kristoff answers.

"Yes," Hinsch responds, holding in violence. "The explosives."

Kristoff rubs his thumbs on the money resting in his palms.

Hinsch continues. "I will explain."

President Woodrow Wilson sits in the oval office. He is weary, running for re-election while he's spent two years struggling with the defining question of his time: Should America join World War I?

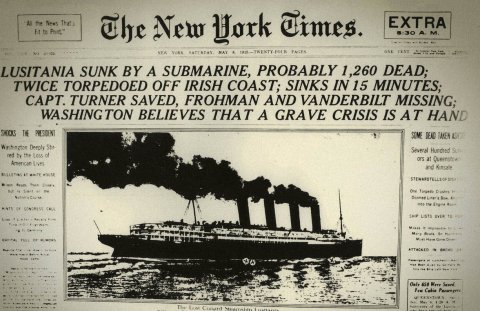

Wilson has resisted battle, even after a German submarine torpedoed the cruise ship, The Lusitania, killing 128 Americans. The New York Times has called on him to, "make sure the Germans shall no longer make war like savages drunk with blood." And still, Wilson does not bend. With every passing day, his stance becomes harder to maintain.

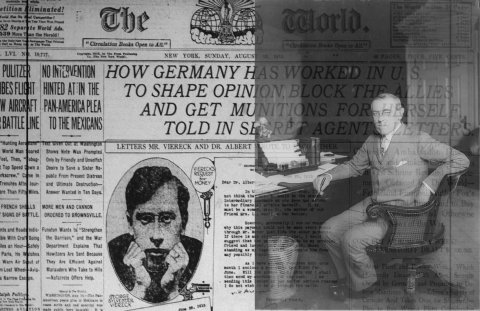

On Wilson's desk is a copy of The New York World. The headline shouts: How Germany Has Worked in U.S., Told in Secret Agents Letters. He calls for an aide. Months before, Wilson had been told of a German-run, fake-passport operation in Manhattan. He asked his attorney general to investigate, but to make sure its existence remained quiet until, "we have no choice but to act."

Now, he tells his aide urgently: "I am sure the country is honeycombed with German intrigue and infested with German spies."

Teddy Roosevelt scans the roaring crowd before him and screams. "Justice! It never was and never will be provided by the weak." Dressed in his famed roughrider uniform, the former president has been Wilson's harshest critic, angered by his inaction. Still beloved, still revered, Roosevelt knows the crowd is behind him. Newspapers print stories every day that hundreds of thousands of German-Americans living in New York have instructions to mobilize and take over the city.

"Those hyphenated Americans," Roosevelt yells, "terrorize us."

From the windows of the brownstone on 15th street in Manhattan there is the faint sound of opera. A single voice escapes through the thick glass. Inside, a buxom woman—her girth covered by a heavy Victorian-style dress — loudly sings a German aria. Around her are beautiful young American women, clinging to the arms of older men, decked out in German military uniforms.

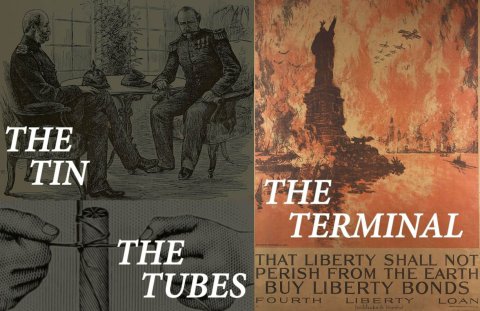

One of the Germans walks into the formal dining room carrying a small tin.

"Careful," a fellow German says to him, smirking. "Avoid vibrations."

Inside are small metal tubes, each filled with combustible chemicals. Several men gather around the dining room table, the tin of explosives resting in front of them. They pull out a map.

"Black Tom terminal," one of them says, pointing at a spot on a detailed drawing of New York Harbor.

"The Statue of Liberty," says another, pointing at nearly the same location.

"The Americans are merchants of death," says the first German. "Selling bombs, selling bullets, shipping them to our enemies."

"They say they are neutral," says the second.

"No," says the first. "They are hypocrites."

Back in the McAlpinhotel, Kristoff fondles his money.

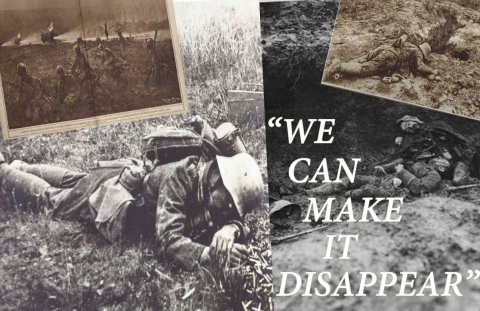

"I've hired men, Michael," Hinsch says. "They've blown up factories where they make the bullets killing our soldiers. And I have bigger plans."

Kristoff is mesmerized. He doesn't feel it when Hinsch slowly pulls the money away from his hands. "We can make it all disappear," Hinsch continues. "We can save lives."

"This will be the best thing to stop the war?" Kristoff finally asks.

Hinsch, normally brash, lowers his voice to a whisper. "Yes," he says, spreading the money out like a fan on the bed. "And this will be yours, if you help me destroy Black Tom."

5 Months Earlier

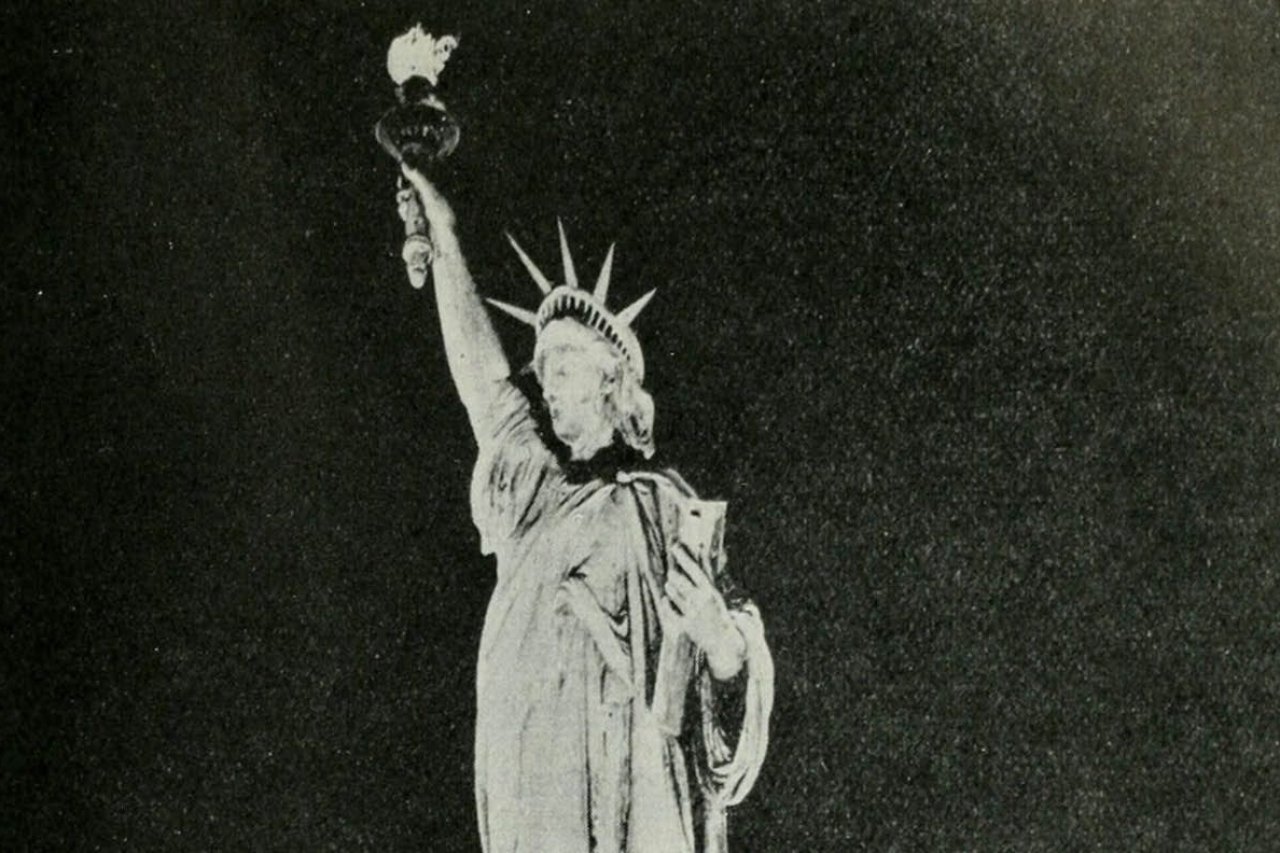

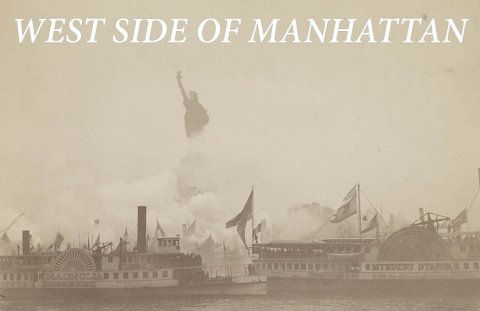

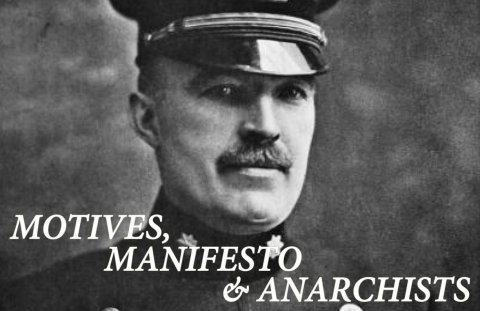

Captain Thomas Tunney, head of the NYPD Bomb Squad, is called to the docks on the west side of Manhattan, along the edge of New York Harbor. It's just past dusk, and the silhouette of the Statue of Liberty is visible in the distance.

Dressed in his high-collar uniform, his jowls starting to strain over the edges, the 40-year-old Tunney has been the bomb squad's boss for five years. He has studied explosives and the motives of bombers, from warring Mafioso to local anarchists. He's seen every kind of homemade bomb.

Tunney, surrounded by his officers, bends down on the deck of a ship docked in the harbor.

"What did they find, officer?" Tunney asks one of his men.

"Something suspicious in the cargo," he answers. "This ship was headed for France."

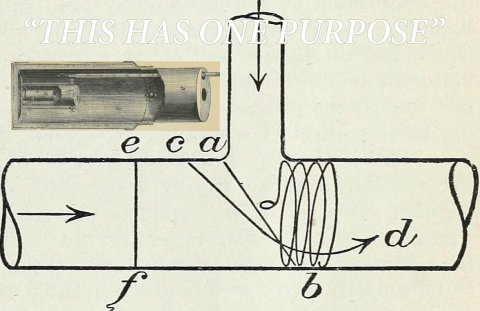

The officer shines his light towards a crack between two huge, tightly-packed, burlap sacks, one labeled "sugar" and the other "grain." Tunney wedges his hand deep between the bags and pulls out a small metal tube, the size of a cigar.

Tunney raises the tube to the flashlight and turns it in his fingers.

"This one is different," he says.

"Smoother than the Italians, more sophisticated than the Irish" says the officer.

"These people took their time," Tunney says. "Spent some money."

Inside the enclosed pipe are two chemicals, potassium chlorate and sulphuric acid, separated into compartments by a small thin disc. When combined, they are explosive.

"This isn't an anarchist working in his apartment," Tunney continues. "This one has purpose."

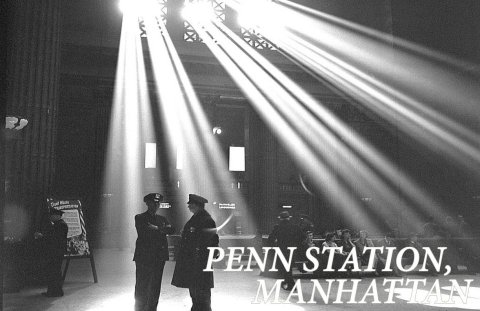

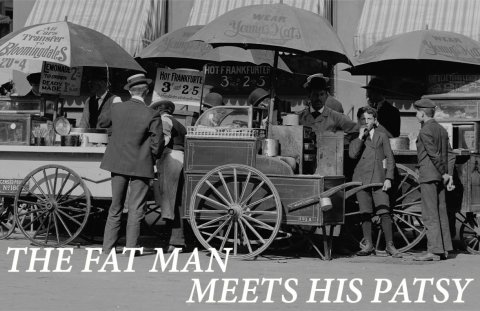

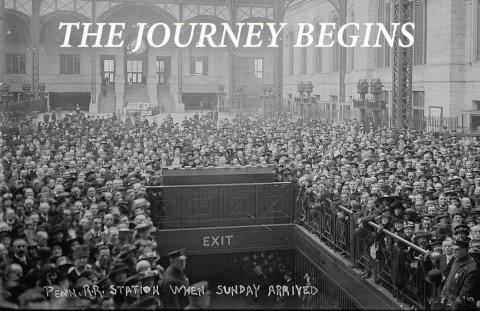

The next day, Tunney and one of his men walk into the old Penn Station. Light pours into the building through the glass-topped, vaulted ceilings. Only six-years-old, it has already become the busiest train depot in the world. It has also become a breeding ground for malcontents.

The block surrounding Penn Station is crowded with merchants selling liquor, newspapers, soap, anything anyone making a quick getaway would need. The air smells of sausages, beef and chicken roasting in food carts. The whole of Europe is represented in these blocks, where newly-minted Americans congregate to share a taste of their homeland.

"Our people are starving," yells a man in a German accent, huddled close to a food cart selling sausages. "We can't get food through the blockade!"

"I received a letter from home," says another German. "The Kaiser has forbidden target practice. Not enough bullets."

Hinsch, the big-bellied, hot-tempered, German, enters Penn Station. He spends many days here, wandering the surrounding streets, listening for discontented voices. Michael Kristoff is among those voices that is loudest. Tall and lean, hungry looking with a sloping chin, flaming red hair and pale blue eyes, he is out of work. Hinsch, standing nearby, has heard him during his many visits.

"There is no such thing as neutrality," Kristoff says loudly, to no one in particular. "At least the British are shooting us in the face."

Hinsch sees Kristoff, a suitcase sitting at his feet, and looks at his wrists. Kristoff is not wearing a watch.

"Excuse me," Hinsch says to Kristoff, his German accent heavy. "Do you know what time it is?"

Kristoff shows Hinsch his empty wrists and shrugs. He's disarmed by Hinsch's accent. "Where are you from?" Kristoff asks.

"Germany," Hinsch answers. "And I agree with you. I hate the Americans, too."

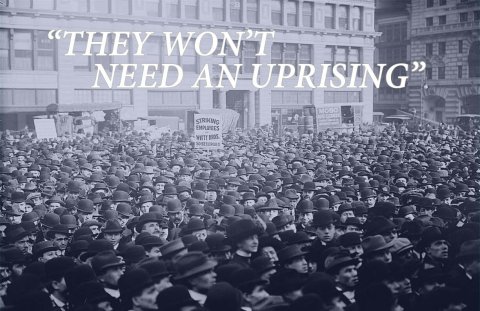

Tunney and one of his men scan the crowds, looking for anything suspicious. His effort is urgent. The discovery at the docks has unsettled him. They stroll past a food cart, surrounded by men with German accents, listening for leads.

"You know captain," says one of his men. "I ordered a hamburger last week. They're calling them liberty sandwiches now."

"I read in the paper they banned teaching German in California schools," Tunney says. "Also saw that a priest in Minnesota was tarred and feathered for giving last rites in German."

"You believe what you read, Captain? Think there's gonna be a German uprising?"

"We've seen what they're planning, son," Tunney says. "They won't need an uprising for that."

While chatting with Kristoff at Penn Station, Hinsch nods to his suitcase.

"Taking a trip," Hinsch asks.

"My sister's," Kristoff answers. "In Ohio. I live with an aunt in Bayonne, just across the harbor. I can't find work here."

"I'm about to take a trip," Hinsch says. "I could use some help. It's easy work, carrying bags, watching my things. When we get back I can help you find a factory job nearby."

Kristoff doesn't hesitate to accept.

Days later, the men begin their trip in Philadelphia. It's early February, 1916.

"Stay here," Hinsch tells Kristoff. "Do not look inside the bags. Do not answer the door."

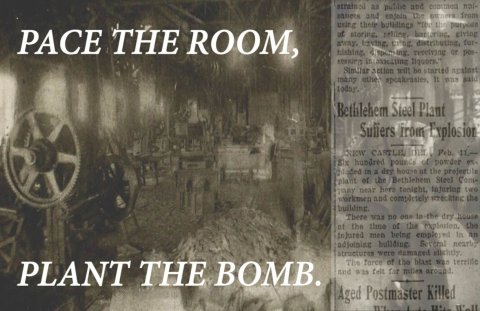

Kristoff does as he's told, pacing the room until late into the night, awaiting Hinsch's return. The next morning, Hinsch saunters through the door and collapses on a bed. Overnight, the Bethlehem Projectile Plant, 70 miles from the city, is destroyed in an explosion.

Hinsch and Kristoff ride the train to Connecticut and then St. Louis and then Detroit. Very little is said. Hinsch reads the paper, Kristoff reads Hinsch. On the way out of Connecticut, there is news about an explosion at the Union Metallic Cartridge Company in Bridgeport. The day after they leave Detroit, the newspaper reports a mysterious fire destroyed a large chemical plant in Cadillac, Michigan. At every stop, Kristoff waits at the hotels, watching the bags, never looking inside.

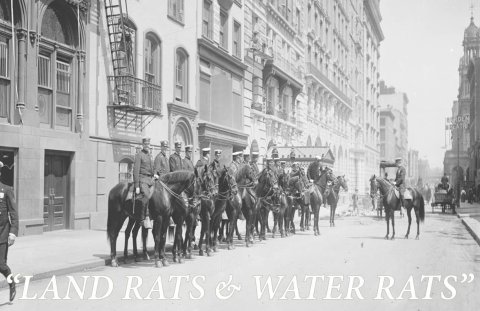

For weeks, Tunney and his men spread out along the docks on the west side of New York Harbor, in search of more cigar bombs, or the men who planted them.

One morning, Tunney gathers his frustrated men and tells them: "On the waterfront, for every thoroughfare which can pass as a street there are a dozen or two alleys, footpaths, shadowy recesses and blind holes. And, as Shakespeare said, there are land rats and there are water rats."

The message: Keep looking.

In Columbus, Ohio, Kristoff can no longer resist looking in the briefcases. While Hinsch is away, he throws one onto a bed and opens it. Inside he sees blueprints and cash. He throws a second briefcase onto the bed. More blueprints. More cash. Before he can close it, Hinsch walks in.

"What are you doing?" Hinsch yells, shaking with fury, lifting his hand to smack Kristoff.

Kristoff recoils, "I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I just wanted…" Before he can finish, Hinsch drops his hand.

They stare at each other.

"Our trip is over," Hinsch says. "We're going back to New York."

Tunney grows frustrated as the mysterious fires on ships leaving New York Harbor escalate. Over several nights his stakeout team tracks a small dinghy motoring between boats with no results. Another evening his men see cargo loaders throwing metal objects overboard. When questioned, the workers casually say they're tossing little bombs, which they find so often they usually dump them without telling a soul.

Back at Penn Station, Hinsch pays Kristoff in cash.

"I've found you a job," Hinsch says. "It's in a factory, Eagle Iron Works, in Jersey City."

"What will I do?" Kristoff asks.

"You'll work, you'll listen, you'll watch," says Hinsch. "And when I call, you will answer."

Kristoff is relieved. His new job will be just a short train ride from his aunt's in Bayonne. But Hinsch didn't choose it for that. Eagle Iron Works sits along the edge of New York Harbor. It's across the street from the largest munitions depot in the country, Black Tom Island.

July 29, 1916

Thomas Tunney sits at his desk in police headquarters, a lieutenant nearby. With every incident he has started a file. At the top of the pile are leads, but no bombs. At the bottom are stories of cigar bombs that disappeared in the night, endings with no beginnings. His pile is as high as it is worthless. He knows something bad is coming, yet he can't do anything to stop it. "There is," he told the lieutenant, "a maddening certainty about it all."

Shortly after 11 pm that night a jittery Michael Kristoff leaves his aunt's house in Bayonne.

"Where are you going?" she asks.

"The factory," he answers sharply.

"Now?"

"I need to pick up my paycheck," he says, slamming the door as he leaves.

Once he's gone, she slowly ascends the stairs to his room. Inside she sees maps with factory locations pinpointed, including Black Tom Island, along with wads of cash. She closes the door quickly, not wanting to know anymore.

By midnight Kristoff, a common face to the Black Tom guards, is strolling around the poorly secured yard. He carries several sticks of dynamite and satchel full of thin cigar bombs, each one containing combustible chemicals. Around him are trains and barges loaded with explosives. One small fire, he thinks, started in just the right spot, and it will all disappear. At 12:30, his mission complete, he walks away from Black Tom, as easily as he had walked on.

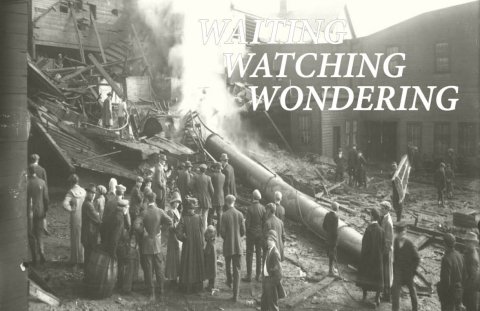

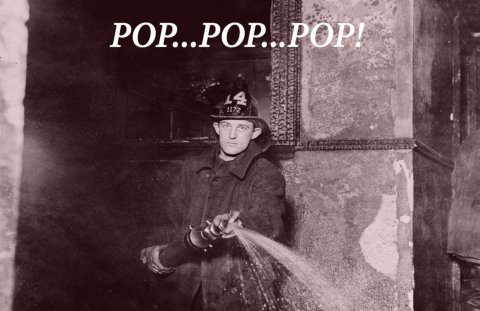

By 12:45 am, shooting from the tops of the railroad cars, are bright white and orange flames. Within seconds there is a pop-pop-pop. The shells are exploding. The Jersey City Fire Department arrives at 1:20 am, but the barge is firing like a machine-gun.

At 2:08 am a barge carrying 100,000 pounds of TNT and 25,000 detonators explodes, "like the discharge of a great canon," The New York Times reports the next day. Firemen standing on the edge of the yard are blown out of their shoes.

On Ellis Island a doctor watches the destruction with a set of opera glasses. A great light fills the sky, shooting sparks into the stars. Within seconds, wood, glass, metal and seemingly all of the water in New York Harbor begin to rain down.

The first explosion devastates almost all of Jersey City. The roofs of the assembly chamber and the courtroom crater. Every shop window on Ocean Avenue, the city's main artery, is blown out. The ceiling at police headquarters collapses on the head of the lieutenant dispatching men to the scene.

In Brooklyn, Tunney is shaken awake by the explosion. As he rushes to the window, he feels the floorboards beneath his feet trembling.

At 2:40 am another massive explosion occurs, sending a pillar of flame skyward. The firemen on a New York City fire boat take cover behind the boat's steel railing to protect themselves from bullets whizzing through the air.

In Manhattan, the windows of every skyscraper along Broadway, Broad and Wall Streets are shattered. At the corner of 42nd and Fifth, across the harbor and several miles uptown from the explosion, the New York Public Library suffers damage and ten fire trucks, responding to different alarms, are gridlocked. Police officers race downtown, chasing the orange glow and rat-a-tat-tat coming from the harbor. It seemed as though the Great War had come to the city.

A few blocks away, at 42nd and Sixth, the explosion causes a water main break, flooding four-square blocks. Guests at the most upscale hotels run into the street in their nightgowns and sleeping clothes, running barefoot across the shattered glass that litters the pavement.

Tunney looks outside his window and the sky is aglow, lit an orange and white. He is certain about what's happened. And who is responsible.

Phone lines between New York and New Jersey go dead. Shrapnel tears into the Statue of Liberty.

As far south as Philadelphia people think they are in the middle of an earthquake. In Maryland citizens call police, concerned about strange vibrations. No one knows what is happening, and no one feels safe.

Michael Kristoff's aunt is wide-awake as dawn approaches. The windows in her Bayonne house had been shattered. She hears footsteps sprinting back and forth across her porch. The running suddenly stops and she hears a pounding on her front door. She refuses to open it until a familiar voice begins screaming. It is her nephew. She opens the door, he pushes her aside and sprints up to his room, yelling, "What did I do? Oh god, what did I do?"

Once morning breaks, the devastation reveals itself. Boats that housed immigrants in the harbor have turned to dust. Craters have formed where solid bedrock once existed. Twisted railroad ties sprout up from the ground, disfigured by an explosion that, years later, scientists would estimate measured 5.5 on the Richter scale.

In Manhattan, ash from the fires mixes with finely pulverized glass to create a black and white dust. Everything in the city is coated, glistening in the sun.

Epilogue

The next morning, The New York Times writes that the destruction of tons of munitions should lead to, "cheering in Vienna and Berlin." Meanwhile, the U.S. Bureau of Investigations immediately claims the explosion at Black Tom is, "an accident." President Wilson, vacationing in Chesapeake Bay, calls the devastation at Black Tom a "regrettable incident." In a few months he will win re-election, campaigning as the man who, "kept us out of war."

Across the harbor from Black Tom Island, Tunney and his men arrive at Penn Station, anxious to question the street vendors. Despite the heat, he's dressed in his high-button uniform. A year from now, Wilson will have declared war on Germany. And Tunney's celebrated bomb squad will make front-page news when it's taken over by the War Department, charged with stopping German plots in the United States. But on this morning, they're just hoping someone slips.

While Kristoff is sleeping, his aunt calls her daughter.

"Something has happened," she tells her. "It's Michael, I think he's part of something horrible."

Four days later, Frederick Hinsch arrives alone at the roof garden atop the Hotel Astor in Times Square. It's dusk, still bright enough to see the colors of the women's dresses on the street below. As Hinsch leans over the balcony, a distinguished-looking man approaches.

"How about that bonfire," Hinsch asks, without turning to face the man.

"That was a lovely scene," the man says, handing Hinsch $2,000. "Perhaps one day you can tell me how you did it."

Hinsch waves him off. "It's better," he says, "you don't know too much."

In late August, Michael Kristoff is sitting in his aunt's house. He does not know the police have been investigating him, tipped off by his aunt and her daughter the morning after the Black Tom explosion. He hears a knock on the door. His aunt, in the kitchen, pretends not to notice. Slowly, he stands. There is another knock.

"I'm coming," he yells.

One more knock. He cannot see the police standing sentry on the other side.

This excerpt from The Detonators is provided by Little, Brown and Company, Copyright © 2006 by Chad Millman. All rights reserved.