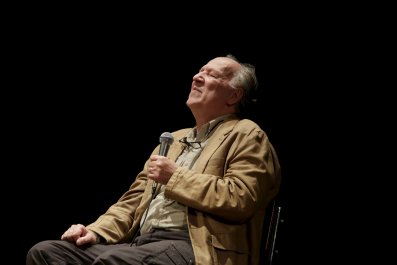

Dr. Leonard Bailey turns 74 in August, but as chief of surgery for Loma Linda University's Children's Hospital, about 60 miles east of Los Angeles, he still puts in 60-hour weeks, starting at 6:30 every morning. Tall and slender with blue eyes and a corona of thinning gray hair, the pioneering heart surgeon performed the world's first successful infant-to-infant heart transplant and has done hundreds of transplants for the tiniest of babies.

"Some weeks, it's 80 to 90 hours, if we do a transplant that goes round the clock, but we seldom do more than two a day," says Bailey of his workload. Despite his hectic schedule, he has no plans to retire. "There's no reason to stop. If you're constantly thinking new thoughts and dealing with new problems, it refreshes your brain cells and makes new connections."

Here in the city of Loma Linda, a high desert Shangri-la known as America's longevity capital, Bailey is not all that unusual. Many of the residents live as much as a decade longer than their counterparts in surrounding communities, and many people in their 70s and beyond are doing jobs we normally associate with someone half their age. While they may seem like remarkable exceptions, they're actually part of a growing phenomenon.

A June report by the Pew Research Center found that the percentage of retirement-age Americans who remain in the workforce has dramatically increased, climbing from 12.8 percent in 2000 to 18.8 percent this year. Roughly one-third of the nation's 65- to 69-year-olds were still gainfully employed, as were a fifth of those in the 70-to-74 range and even 8.4 percent of the 75-plus population.

Several factors are driving this trend. Some of it is financial—the Great Recession of 2008 ripped a big chunk out of retirement savings, and fewer employees these days have fixed pensions, so many people have little choice but to keep working. But others are like Bailey—educated professionals who aren't ready to be cast aside. "What was once viewed as the traditional retirement—living in a retirement community on the beach with a rec center and a golf course—is not the aspiration for the aging cohort of baby boomers or Gen Xers," says Paul Irving, chairman of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging in Los Angeles. "People are living longer, healthier lives, and the entire notion of retirement is being rethought."

There's also a shift in attitudes toward retirement, probably because we're in the midst of the most significant demographic change in history. Up until the 20th century, fewer than half of all Americans reached age 50, but by midcentury, more than 88 million Americans will be over 65, according to U.S. government projections, which has triggered worries that caring for these oldsters could drain societal resources and bankrupt the health care system. Rapidly aging nations like Japan, where nearly 40 percent of the population will be 65 or older by 2060, are bracing for economic disaster because there will be fewer young workers to generate robust and sustainable growth, while pension and health care costs will skyrocket.

But many experts believe horror stories of greedy geezers guzzling scarce resources miss the fact that many of today's seniors are healthier, better educated and more productive than previous generations—and want to keep working.

While some employers worry about aging workers' diminished capacities, rising health care costs and their unfamiliarity with new tech tools, some companies are already finding innovative ways to accommodate an aging workforce. They've launched programs that range from mentoring programs that pair up experienced veterans with younger colleagues to phased-in retirement plans that allow people to work flexibly or on part-time schedules. These programs let companies capitalize on the legions of workers in their 60s who'd miss the camaraderie and the paycheck but not the hectic pace that comes with a full-time job.

There are good reasons for companies to do this. Older workers are more loyal and stay on the job longer than their younger counterparts, according to a 2014 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This reduces turnover and minimizes costs for hiring and training replacements. Older employees also have a depth of experience, contacts and skills, which often means they can come up to speed faster than the youngsters, and they can be more adept at navigating in the corporate world.

The staff at Michelin, the tire manufacturer that has its U.S. headquarters in Greenville, South Carolina, is practically geriatric: Nearly 40 percent of their 16,000 employees are over 50, and most of them have been with the company for two decades or more. Michelin, which is consistently ranked by AARP as one of the best places for older workers, has a suite of alternative arrangements designed to keep people on the job. They range from flextime, compressed work schedules and job-sharing to telecommuting and phased retirement programs. Even when staffers opt for that gold watch, they're regularly informed of employment opportunities, such as temporary work assignments, consulting or contract work, or even full-time jobs. "People want to work less and have a bit more flexibility but don't want to drop out completely," says David Stafford, Michelin's executive vice president of human resources.

And Michelin's not just holding on to its white-collar professionals; it puts just as much effort into retaining skilled tradespeople—the automation experts, electricians and technical support staffers who maintain production on the factory floor. "These are the hardest jobs to fill because so few have this kind of expertise," says Stafford. "Manufacturing companies are all facing these kinds of shortages today."

MEI Technologies, an aerospace and technology company across the street from the Johnson Space Center in Houston, actively recruits retirees, targeting former NASA engineers and retired military people to work on a project basis during rush periods. "Work flows have peaks and valleys, and this on-call workforce helps us meet customer needs," says Sandra Stanford, director of human resources at MEI Technologies.

Even in the notoriously youth-oriented tech world, some companies are crafting corporate benefits to keep and attract older workers. At NerdWallet, a financial information website headquartered in San Francisco, nearly a third of the writing and editing staff is 50 or older. "I want the best talent, I want a mix of it, and we're highly selective of who we hire," says Maggie Leung, the company's senior director of content, who sifted through more than 8,000 résumés to field an editorial team of 90. The company allows telecommuting for professionals who don't want to uproot their families or spend a giant chunk of their paychecks living in the Bay Area's extortionate real estate market.

Leung says she aggressively recruited a highly experienced automotive writer in his mid-60s. Phil Reed, who's been writing about cars for more than two decades, telecommutes from Long Beach, California. He says at first he felt somewhat out of place when he traveled to San Francisco for staff meetings.

"There were times I felt conscious of my age," recalls Reed, who normally does weekly video conferences with his boss and colleagues. "But I was pleased to find that there were quite a few editors in their 40s and 50s, and it wasn't just a startup with kids running around. Originally, I had planned to retire in a couple of years. But I like being involved and being part of a team. If things keep up like this, why would I retire?"