What's the value of a dollar? I'm not asking in the sense of "proving to your parents that you understand hard work by shoveling your elderly neighbor's driveway" or "selling your car so you can spend six months in Guatemala." I mean if I tried to sell you a $1 bill right now—an average, slightly wrinkled bill—what would you pay for it?

The answer seems obvious, tautological even. Its value is in its name. Its price tag is printed all over it. It's worth itself. Or is it? To find out, I decided to try to sell a dollar on eBay.

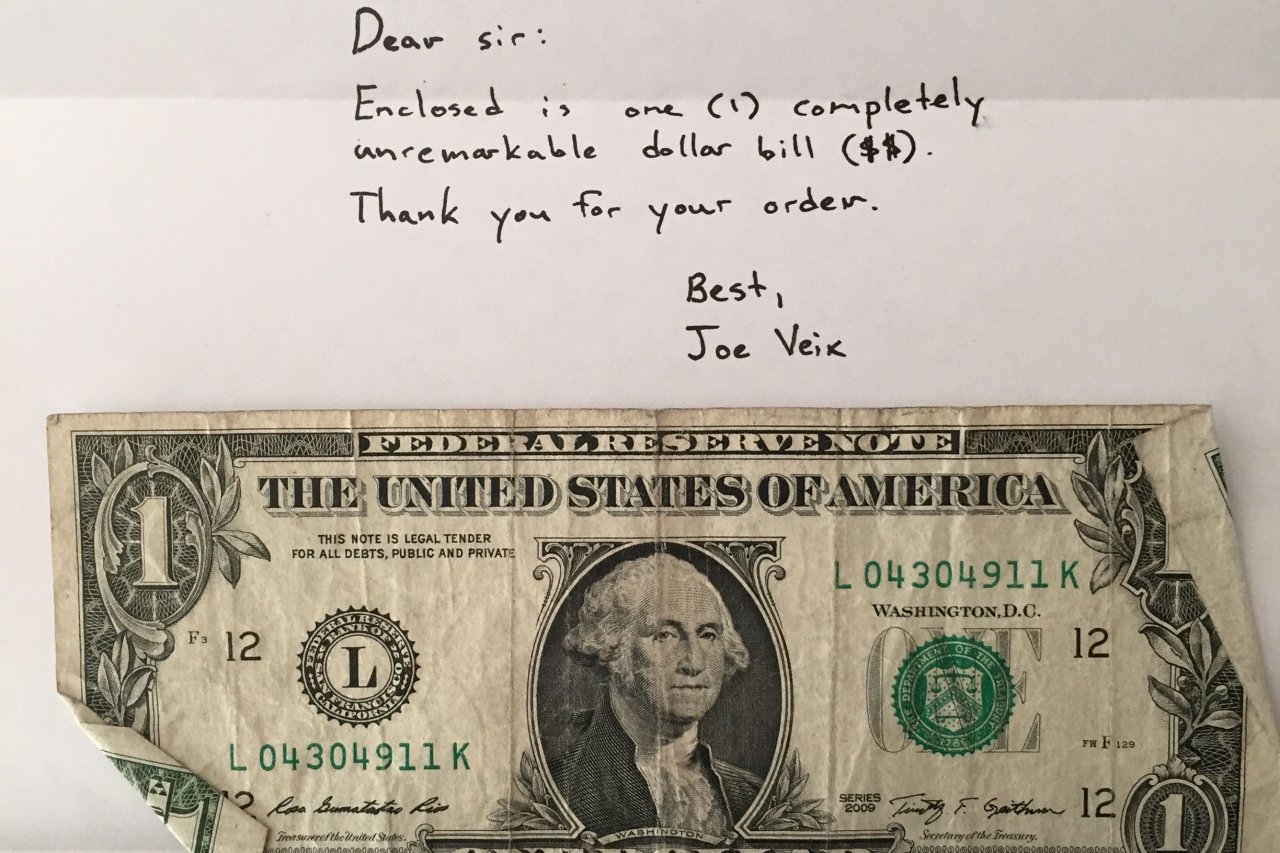

I took a random bill out of my wallet, took a few photos from different angles and then wrote up the listing under the username smashmouth420. I filed the auction under the Coins & Paper Money category—which I suppose is usually reserved for coin collectors—and titled it simply "one dollar bill."

"I'm selling one of my dollar bills. i got it as change after buying a burrito with a ten dollar bill," I wrote in the auction's description. "I hate to part with it, but sadly i just don't have the space in my apartment. it's great for anyone who likes or uses money. it's a 2009 model, used, light/dark green, with former President George Washington on the front. made in the good old USA!"

I then posted the listing on social media. Within an hour, someone bid on it: 5 cents—a great deal, until one factored in the $2.62 for shipping. The following morning, the price jumped to 10 cents.

Naturally, users messaged me with questions. I tried to be as helpful as possible: "Was this used dollar bill touched by someone famous?" No. "Will you ship it safely to keep its rumpled condition as is?" No. "How do I know this is a real dollar? Do you have any documentation that proves it is actual U.S. currency?" No.

Soon a low-stakes bidding war between six people started. The price jumped in 10-cent increments until it reached $1. One second later, the price hit $2. A 100 percent profit, without doing any real work or producing anything worthwhile for society. I felt a mix of joy and deep self-loathing. This must be how bankers might feel, if they could experience human emotions.

Can't Put a Price on Stupid

Why were people willing to overbid on a lousy dollar bill? Here was an auction with perfect information, in which the value of the object was explicit. Unlike the "dollar auction" created by economist Martin Shubik, in which the price is driven upward by the nature of the game (the second-highest bidder has to pay out what he or she bids, which gives people incentive to keep bidding), people in this case just seemed to want my dollar bill.

There are plenty of examples of this kind of irrationality playing out in a market: In 2005, Kyle MacDonald traded a worthless red paper clip for progressively more valuable objects. By his 14th trade, he got a two-story farmhouse in Kipling, Saskatchewan. In 2013, poet Vanessa Place created a poetry chapbook made of 20 $1 bills and sold it for $50. It sold out in an hour. In 2014, Zach Brown raised money on Kickstarter to make a bowl of potato salad. He ended up raising over $55,000.

Perhaps the objects gained value through association with an interesting narrative, or they became art objects. Or maybe people just like blowing their money on hopeless causes. After all, Gary Johnson's presidential campaign raised nearly $9 million.

Seventeen bids and three days later, the auction closed at $3.50. The winner was Erick Sanchez, in Washington, D.C. After his payment cleared, I slipped the dollar bill into an envelope and mailed it to him.

I had previously met Sanchez while covering him for a story last year. He raised $30,000 on Kickstarter to donate money to another Kickstarter, so that Kenny Loggins—the '80s pop singer most famous for movie soundtrack hits like "Footloose" and "Danger Zone"—would play in his parent's suburban living room. It's fitting that Sanchez got my dollar, as he is familiar with online stunts that waste other people's money.

I asked him why he was willing to blow his money on my auction. "It wasn't just any dollar bill," he explains. It gained an ineffable value by being part of a dumb joke, just like it might if a B-list celebrity signed it. "Let's say Corey Feldman was selling a dollar on eBay. He'd probably get like $20 for it."

So where did the bill end up? Sanchez says he thought about framing it but changed his mind and spent it on a Powerball ticket. "I was convinced the power of the bill would give me the power of the ball," he says. "I lost."

To the extent that any conclusions can be drawn from this very unscientific experiment, value is incredibly flexible, even for something seemingly immutable like currency. It's not like one needs a cheap internet stunt to determine that markets are irrational. Just look at the housing crisis or the economic pressures preventing us from stopping humanity's slow global warming suicide. Still, it's a useful notion to remember whenever some libertarian billionaire like Peter Thiel demands that we preserve the sanctity of the free market by grinding the bones of poor people and using them for pesto. Markets are irrational.

Pretentious stabs at larger meaning aside, there's at least an answer to that first question: The value of a dollar bill is precisely $3.50. Plus shipping.