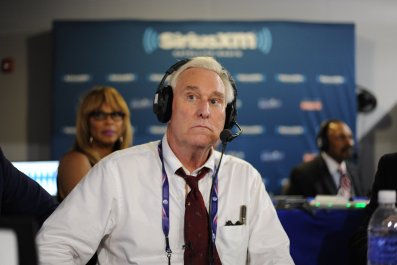

Charles Harder does not want to be recorded, one of the very few interview subjects I've ever had make that demand. Military officers at Guantánamo Bay were fine with it; the convicted murderer in a New York prison was fine with it; countless politicians and government officials were fine with it. But not this Beverly Hills lawyer to the stars, which means that as we sit down for lunch, I am forced to eat with one hand and scrawl notes with the other. I don't want to give the idea, however, that Harder was torturing me because he likes to torture journalists, though that accusation has been made. A client list that includes Jude Law and Amber Heard means, to borrow from Falstaff, that discretion is the better part of disclosure.

My notes from that meal are sparse, because in addition to not wanting to be recorded, Harder frequently goes off the record. Having become somewhat famous for defending the obscenely famous, Harder has a deceptively casual manner that disguises a master gardener's impulse for pruning media curiosity into the kind of flowery coverage that reflects well on his practice and clients. He will not so much as acknowledge that he works for Roger Ailes, the deposed Fox News chairman, though Harder's name appears on a threatening letter to New York magazine. Nor will he say how Melania Trump came to be his client in a lawsuit against the Daily Mail, which alleged, in an article since removed, that the wife of the Republican presidential nominee worked for an escort service in the 1990s. Nor will he talk—on the record or off—about his politics. Or his family. "I have the most boring life in the world," he says—on the record.

Harder will gladly talk about one recent case, the one that led to him being called "Hollywood's favourite lawyer" (Financial Times) and "arguably the highest-profile media lawyer in America" (The Hollywood Reporter). That case is Bollea v. Gawker, in which Terry Gene Bollea, better known as the professional wrestler Hulk Hogan, won a $140 million civil judgment in a Florida court against Gawker, the Manhattan-based gossip website that in 2012 posted a brief excerpt of a covertly made recording in which Bollea was seen having sex with the wife of a friend. Bollea's victory drove both Gawker Media and its founder, Nick Denton, to declare bankruptcy.

Some see in Bollea's victory a setback for the very notion of a free press that, presumably, should have the right to publish even excerpts of a sex tape, if that sex tape is determined to have news value. Harder disagrees, painting Gawker as a uniquely bad actor with a destructive impulse. When I ask him what doomed Gawker, he answers with a single word: "Gawker." And though much of the Manhattan media establishment mourned Gawker's demise as one might have the fall of Rome, Harder shows no contrition. "If it has a chilling effect on irresponsible journalism? Awesome!"

Bold-Faced Faces

A man of aquiline features that are as controlled as his speech, Harder looks like he may have walked out of the Brooks Brothers store on Rodeo Drive a fully formed creature of Beverly Hills, spending his nearly 47 years on Earth without a single hair ever out of place. He was, in fact, born and raised in the San Fernando Valley, in a ranch-style house where his parents (his father is a financial consultant, his mother a homemaker) live to this day. He went off to college at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and biked across the country during one summer vacation. He recalls being particularly enamored of Kansas. "I really liked Kansas," he says. "The friendliest people I have met on planet Earth."

Long before he ever sued a journalist, he briefly became one, serving as the managing editor of the short-lived Santa Cruz Independent, a weekly "on the boring side" that was to serve as a counterbalance to more liberal publications on an exceedingly liberal campus. After earning his law degree, Harder clerked for A. Andrew Hauk, a federal judge who earned notoriety for social views that today would likely get him tossed from the bench. For example, Hauk dismissed a case of DDT contamination against the Montrose Chemical Corporation, complaining that environmentalists were "do-gooders and pointy-heads running around snooping." Harder worked on that case and once considered going into environmental law, only to conclude that the field "seemed a little boring."

He eventually came to work for Lavely & Singer, an entertainment law firm whose defining figure was Martin Singer, the Brooklyn-born son of a Holocaust survivor. Hollywood requires several species of lawyer: the ruthless litigator, the capable deal-maker, the doyen of divorce. Singer turned what The New York Times called the "niche practice" of "shielding stars and their adjuncts from annoyance" into a major firm.

Harder flourished. He usually won his cases via settlement, and he did it quietly, without exposing his famous clients to undue publicity. Most often, those clients were seeking redress from a vendor who'd used a famous face in an advertisement. Harder made them stop and pay for it: a furniture company that named pieces after Clint Eastwood; a similar case involving a furniture line named after Humphrey Bogart; a Canadian fireplace-maker that sold its wares by using a picture of Jude Law.

In 2008, Harder left Singer's practice for Wolf, Rifkin, Shapiro, Schulman & Rabkin LLP, a bigger Los Angeles firm that may have given the still-young lawyer an easier route to making partner. He seemed well on his way, in 2009 winning arbitrated cases over domain names for Sandra Bullock, Cameron Diaz, Kate Hudson and Sigourney Weaver. Two years later, he won $18 million for Cecchi Gori Pictures in a dispute over movie rights.

Then, in the fall of 2012, came a call from the office of Peter Thiel.

Execution by Surrogate

Harder bristles at being called Thiel's peon, though one could have a worse patron than the billionaire founder of PayPal. "How is what Peter Thiel did different than what public interest organizations do?" he wonders. That's a fair comparison, though not an entirely accurate one. When, for example, the Sierra Club sues the California Coastal Commission, it does so openly and, presumably, for the public interest. Thiel's desire to sue Gawker out of existence stemmed from his need to exact revenge over a 2007 post that outed him. That post may have been of questionable journalistic value, but it passed legal muster, so Thiel waited for Gawker to make another mistake.

That mistake took place on October 4, 2012, when an editor for Gawker named A.J. Daulerio published a post titled "Even for a Minute, Watching Hulk Hogan Have Sex in a Canopy Bed Is Not Safe for Work but Watch It Anyway." The post excerpted about two minutes of a 30-minute recording, surreptitiously made, of Bollea having sex with Heather Clem, the wife of his close friend Bubba "the Love Sponge" Clem. Bollea's lawyer, David Houston, sent Gawker a letter demanding that the video be taken down, but Gawker refused.

It's not known how Thiel recruited Harder, though it has been reported that a representative of Thiel simply called Harder and asked him to take the case. The former wrestler's own coarse sensibilities could not have mattered much to the Stanford-educated Silicon Valley titan. He wanted only to bring down Gawker, and to do it without his own involvement revealed.

Harder filed suit against Gawker on October 15, 2012, charging that the post was "a shameful and outrageous violation of Mr. Bollea's right of privacy by a group of loathsome Defendants who have no regard for human dignity and care only about maximizing their revenues and profits at the expense of all others." Shortly thereafter, Harder left Wolf, Rifkin, taking the lucrative case with him and starting a new firm, Harder Mirell & Abrams LLP.

This led to some grousing, as Forbes has reported, that the firm "has made lawsuits against Gawker its 'bread and butter,'" with Harder taking on two other cases against the site.

After more than two years of pretrial battle over the post (the video was eventually removed from the site), Bollea v. Gawker finally went to trial last spring in a state court in St. Petersburg, Florida. As late as last March, however, a settlement appeared to be close. Yet none took place, even though a trial promised the worst kind of publicity for Bollea. "Why would Hogan reject what must have been multi-million dollar offers?" wrote the legal blogger Dan Abrams. It's now clear that Bollea didn't settle because Bollea was merely a soldier in Thiel's war.

The trial lasted 15 days. Harder spent much of his time inside the courtroom sitting quietly by his client. "At least initially, Harder's presence was a mystery to me," says Anna Phillips, who covered the trial for the Tampa Bay Times. "Although he handled some of the pretrial matters, he played almost no role in the actual trial—most of that work was shouldered by the Tampa attorneys. He seemed to be supervising rather than participating in the proceedings, but it only became clear later on why that was."

Much of the day-to-day courtroom work was done by Tampa litigators Kenneth Turkel and Shane Vogt, of Bajo, Cuva, Cohen, Turkel. It was Turkel who selected the jury that eventually awarded his client $40 million more than what the lawsuit demanded; it was Vogt who gave the opening statement; Turkel cross-examined Denton, making him read the salacious post accompanying the Bollea sex tape; Vogt cross-examined the author of that post, Daulerio, who conceded that showing Bollea's penis lacked "news value," thus throwing Gawker's entire defense into question; Turkel delivered the closing argument, in which he charged Denton with "playing God over Bollea's right to privacy."

Although he acknowledges the work by Turkel and Vogt, Harder makes plain that he was the mastermind behind Gawker's demise and touts the trial as an important reminder that First Amendment freedoms have limits. "Think twice before you invade someone's privacy or violate their rights," he wrote in a victory-lap op-ed for The Hollywood Reporter.

Defamation R Us

Despite the enormous award, Terry Bollea is unlikely to soon see a $140 million deposit in his checking account. With both Gawker and Denton having filed for bankruptcy, the appeals process has come to a stop. The generous award by the jury could stand, or shrink, or be the subject of an even-longer court battle, one that could potentially reach the Supreme Court and thus become a landmark ruling on newsworthiness in the digital age.

"Courts are struggling to draw the line right now," explains Amy Gajda, a media law expert at Tulane Law School, with the standards of print media being challenged by online sources where a single person can be the publisher, editor, author and ombudsman of a news site visited by millions. Rules made for The Saturday Evening Post don't work in a world ruled by TMZ and Matt Drudge.

Harder has been eager to paint Bollea v. Gawker as a precedent-setter, one that is likely to brush back the kind of online journalism practiced by Gawker. But his primary mission, critics say, was not to amend First Amendment case law but, rather, to be Thiel's hit man.

Gawker made Harder famous. Shortly after that case ended, he became notorious. He did this by taking on the case of Melania Trump over the summer. Harder sued the Daily Mail , asking for damages of $150 million (the blogger and conspiracy theorist Webster Tarpley was also named in the suit). The Daily Mail took down the article, but the suit continues. Harder puts the matter plainly: "A publication cannot say you were a prostitute in the 1990s if you were not a prostitute in the 1990s."

Just days after taking on Trump as a client, Harder added disgraced Fox News founder Roger Ailes to his roster of the maligned. Ailes's target is likely to be Gabriel Sherman of New York magazine, who wrote a book about Ailes and has more recently chronicled in great detail his history of alleged sexual harassment against female employees at Fox News. He won't talk about the case, but Lauren Starke, a spokeswoman for the magazine, has acknowledged receipt of a letter from Harder, one that suggested a potential defamation lawsuit.

On October 13, Harder was in the news again. The previous day, People magazine published an account by Natasha Stoynoff, in which she claimed that Donald Trump had been sexually aggressive toward her during a 2005 interview with him. On the evening of October 13, Melania Trump tweeted a photo of a letter from Harder to People editor-in-chief Jess Cagle alleging that a portion of the account, in which Stoynoff describes running into Melania Trump in Manhattan, was "completely fictionalized." He gave the magazine 24 hours to remove that passage, issue a retraction and apologize.

Cagle stood by Stoynoff's account, echoing Gawker's defiance over the Bollea sex tape. Stoynoff's story has infinitely more news value than a post about the lurid doings of a minor celebrity, yet Harder isn't likely to make that distinction.

"Harder really has assembled in one place the most committed enemies of liberal democracy," Gawker founder Denton tells me in a text, citing his work on behalf of Ailes and Trump. "I'm not sure how much journalism would be left if Harder had his way."