On a winter afternoon that threatened tornadoes, retired federal judge U.W. Clemon stood at a window 31 floors above Birmingham, looking south. In the foreground was the University of Alabama at Birmingham, whose medical center powers the city's economy. To the west, railroad tracks snaked between warehouses, vestiges of boom times, when Birmingham was known as "the Pittsburgh of the South." On the horizon rose Red Mountain, a slight green ridge. Clustered on the other side of its hump, outside the Birmingham city limits, are some of the wealthiest suburbs in Alabama: Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, Hoover and Homewood. They have the best schools in the state, and although Alabama has some of the worst schools in the nation, those suburbs frequently make it onto national best-schools lists. Many medical center faculty members live in these "over the mountain" suburbs, as do older Southern families.

Clemon did not go to school over the mountain. His grandparents were sharecroppers in Noxubee County, Mississippi. His parents left for Alabama, where his mother worked as a domestic for a white Birmingham family, while his father was a bricklayer's helper. He started at the Dolomite Colored Elementary School. "We had outside privies," he remembered over lunch at City Club Birmingham. The crowd was light. Other than the servers, he was the only black person in the room. At one point, two white men came over, and one of them greeted "the judge." The other asked if the judge was famous, and the first one said yes, he was.

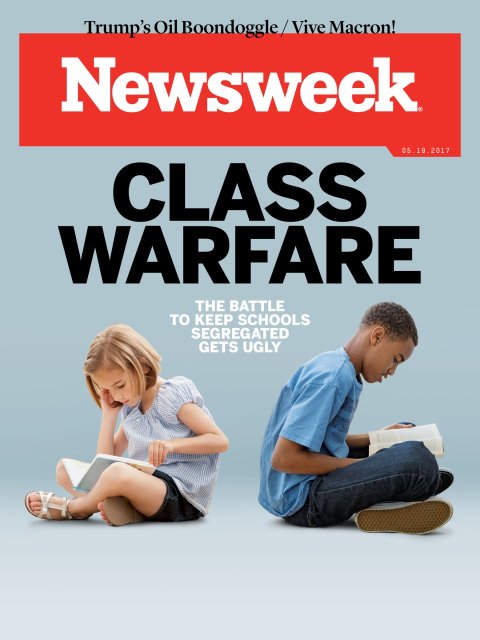

Clemon went to Miles College, right outside Birmingham, and became involved in the civil rights movement, working with Martin Luther King Jr. He jokingly recalled unfavorable coverage the movement received from Newsweek in the 1960s. When I mentioned that I hoped to do archival research at the Birmingham Public Library, Clemon chuckled. "I desegregated that," he said.

Clemon went to Columbia Law School in New York City, then returned to Birmingham to practice civil rights law. In 1971, he argued Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, in which a black parent sued the county school system, which she claimed was segregated by race. The federal judge agreed and ordered the schools to integrate. The schools of Jefferson County (the schools of Birmingham itself are a separate entity) remain under that decree to this day.

Clemon eventually became Alabama's first black federal judge, joining the U.S. District Court that ruled in the school desegregation case, in the Northern District of Alabama. He stayed on the bench for nearly three decades. In what must have been a surreal moment, the descendant of Southern slaves retired in early 2009 with a resignation letter to Barack Obama, the nation's first black president.

More recently, Clemon has found himself in another surreal situation. This past winter, he was in court to argue Stout v. Jefferson County once again, this time because a middle-class Birmingham suburb called Gardendale wants to leave the Jefferson County school system. Gardendale, which is mostly white, says race has nothing to do with its push for secession: It simply wants to control its schools.

Clemon is skeptical. "The intent is to create a local school system where they will have control over who comes in and that they will minimize the number of blacks who come in," he told me in his raspy, slightly mischievous baritone. Local control has become a popular rallying cry in municipalities across the nation—including liberal states like New York and California—that want to form their own school districts. They all have their reasons, and the reasons all sound reasonable, but Clemon believes he knows what motivates Gardendale and at least some of its counterparts around the country, which is schools that share a single feature that mild suburbanites, with their secret yearnings, will not name. But Clemon, who faced off against Bull Connor and his water cannons and his dogs, will: "No blacks."

The Mason-Dixon Line in South Boston

The most remarkable thing about school integration in the United States is how rare it is, and has always been. The Supreme Court struck down separate but equal schooling with 1954's Brown v. Board of Education ruling, but it fell to federal judges of the 1960s and early '70s to enforce that decision with orders like Stout v. Jefferson.

Such court orders were frequently unpopular; when the opponents of integration lost in the courts, they took to the streets. The resistance reached its apex in 1974, when the blue-collar Irish of South Boston resisted the yellow school buses that had come to symbolize integration; they were as feared and loathed by the populace as the tanks of an invading army. Yet the buses came and went, in Boston and elsewhere. By 1988, widely acknowledged to be the high point of school integration in the U.S., nearly half of all black children attended a majority-white school. An achievement gap that once appeared to be intractable suddenly seemed like something that could be closed in a generation or two.

Since then, however, the gains of Brown v. Board have been almost entirely reversed. Last year, a report by the Government Accountability Office found "a large increase in schools that are the most isolated by poverty and race." Between 2000 and 2014, the number of schools the report deemed H/PBH—that is, "high poverty and comprised of mostly Black or Hispanic students"—more than doubled, from 7,009 to 15,089.

An even more astonishing statistic appeared in a Century Foundation report, published three months earlier, about schools that used socioeconomic status, or class, instead of race as a means to integrate schools. (There are fewer legal and social barriers to socioeconomic integration, but the result is effectively the same.) The Century Foundation concluded that only about "8 percent of all public school students currently attend school districts or charter schools that use socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment." The report's tone was hopeful, because while the number of districts around country that consciously practiced class integration was a paltry 91 out of more than 13,000, that's more than double what it was in 2007.

Conscious attempts at integration are rare today because the same court that struck down separate-but-equal promptly struck down the best remedy for it. In 1974, 20 years after Brown v. Board , the Supreme Court ruled in Milliken v. Bradley that integration could not take place across district lines, so that Detroit, where the case was brought, was prevented from integrating by exchanging its kids with white and wealthy Bloomfield Hills. In 1986, in 1991 and again in 1992, an increasingly conservative Supreme Court said it wanted desegregation orders lifted once certain conditions were met. The Supreme Court's most severe blow since Milliken came in 2007, in the Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 case, in which it prohibited the use of "explicit racial classifications" in school admissions. Wrote Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., "The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race." By conflating integration with discrimination, Roberts effectively reversed Brown v. Board.

The breaking away of school districts is a related phenomenon, one that has frustrated the work of integration by appealing to smaller local concerns over grander public ones. More and more, parents see a school in the context of what it can achieve for their child: Education for all has lost out to Princeton for mine.

Resegregation is not restricted to the South. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a wealthy suburb that feeds into Northgate High School is trying to separate from the Mount Diablo Unified School District. Northgate's median income is $126,000, about $50,000 higher than that of the Mount Diablo district. Were Northgate to break away, it would be 65 percent white and only 8 percent Latino.

Proponents of separation in Northgate use exactly the same coded language as those in Gardendale. It is the language being used by secession-seeking districts like East Baton Rouge, in Louisiana, and Malibu, in California, which wants to leave the Santa Monica system. The latter fight is especially bizarre because it is taking place in one of the most privileged enclaves of Los Angeles. "Parents say they are eager to detach themselves from overly bureaucratic school administrations," NBC News reported in late 2014 of Malibu's efforts, which continue to this day, thousands of miles from the hills of Alabama but virtually identical in its social contours. "Others worry that their association with schools that serve at-risk students hurts property values."

The Best Places to Live

Gardendale is not one of the "over the mountain" Birmingham suburbs. It is in north Jefferson County, less hilly and less wealthy than southern suburbs like Mountain Brook. In the 19th century, the settlement was called Jugtown because there was a jug factory there. There were coal mines nearby too, and the city has retained the vestiges of its blue-collar past. People live comfortably there, but not easily. Gardendale's median household income is $56,967, whereas Mountain Brook's is $126,534. Gardendale is 83 percent white. Mountain Brook is 96.5 percent.

There had long been a small group of powerful men in Gardendale—many of them parishioners at the Gardendale First Baptist Church, the town's most prominent civic institution—who decided it was going to become more like Mountain Brook by attracting the well-to-do young families that were, by then, moving farther south, to the exurbs of Shelby County. They wanted Gardendale to do what six other towns in Jefferson County had done: split from the county school system. The centerpiece of the new, independent Gardendale Board of Education would be a $55 million high school Jefferson County had just built in the middle of town for its own system.

By 2013, there finally seemed to be sufficient public will to break away from Jefferson County. That year, Gardendale decided to hold a vote on a new property tax to fund its four schools, which would serve as a referendum on secession. Right before the tax vote, an advertisement appeared in The North Jefferson News. It pictured a white girl. Above her was a question: "Which path will Gardendale choose?" The ad listed "Places that chose NOT to form and support their own school system," including Center Point, Pleasant Grove and Hueytown, all of which are majority black. It also lists districts that seceded from Jefferson County and "are listed as some of the best places to live in the country": Homewood, Hoover, Vestavia and Trussville. All those school systems are very good. They are also very white.

The property tax passed. The following spring, Gardendale formed its own board of education. For the position of superintendent, the city hired Patrick Martin, a young administrator who'd run a school district in central Illinois.

The Gardendale school system prepared to open in the fall of 2014. The city's leaders seemed either unaware or uninterested in the inconvenient fact that Gardendale was bound by Stout v. Jefferson County, which forced Jefferson County to integrate its facilities, students and teachers. Yet other Alabama municipalities had successfully navigated Stout , most recently in 2005, when Trussville pulled its schools out of the county system. Gardendale was justified in thinking that it too could leave the Jefferson County school system.

Jefferson County, however, proved less willing to divorce. There was that $55 million school, and there was the Stout desegregation order, which the county argued would be hurt by Gardendale pulling away so many white students. Gardendale, for its part, has tried to avoid arguments about race, which it must know it cannot win. It claims instead a basic American right, which is the right to be left alone.

Poorer and Blacker

Gardendale High School looms over Gardendale the way the Eiffel Tower looms over Paris. Two enormous wings meet at a colonnaded atrium that looks out at the town's modest center. The red brick and white cornices are both Federal touches, but the building's size and youth are less suggestive of history, with all its varieties of darkness and decay, than of a present-day suburban optimism and health. This continues inside. The hallways are clean, and the children who pass through them seem happy. The array of playing fields, all neatly groomed, seems to stretch into Mississippi.

I drove around Gardendale with Stan Hogeland, who entered politics after 35 years of employment in the town's parks and recreation department. Today, he is the mayor, but much of our tour involved the handsome playgrounds and manicured parks he helped create and manage. "I'm actually prouder to have retired as parks and rec director than I am to be mayor," Hogeland says.

This surely had to do with the nasty secession fight he inherited. In the spring of 2014, as the separation seemed to be moving forward, Jefferson County asked Gardendale for $33.1 million to compensate for the loss of that new high school. Gardendale appealed to Thomas Bice, then the state superintendent of education, who said in February 2015 that Gardendale owed only $8 million. The following month, Jefferson County filed a motion to U.S. District Judge Madeline Haikala, who oversees the Stout integration order.

The county argued that every secession left its district poorer and blacker. "In Jefferson County, splinter districts have historically been predominantly Caucasian and comparatively affluent," wrote the lead Jefferson County attorney. "They are widely perceived as offering a superior public education experience and are magnets for families who can afford to pay the 'tuition' represented by comparatively high property values."

Gardendale's argument was simple: us too. "This Court has exercised jurisdiction over newly formed separate school systems such as Hoover, Leeds and Trussville. Granting intervention for the Gardendale Board would be consistent with previous decisions of the Court." Its case was based firmly on precedent.

Hogeland believes Gardendale needs its own schools—with the new high school as the linchpin—to thrive. As part of the county system, the secessionists say, Gardendale will remain mired in mediocrity, and they cite the example of a "black gentleman" who was an executive at Regents Bank. He was relocating his family to Homewood, which now has the best schools in Alabama.

"People will not move here," Hogeland told me with grim certainty, "to be a part of the Jefferson County school system."

'Empty the Clip'

"I don't see racism in this community," says Jeff Dennis, who owns a jewelry store in a downtown strip mall. "I really don't." He recognizes that if Gardendale breaks away, it would lose some minority students, but this is, in his mind, an unfortunate but unintended consequence. "I don't think anybody has come down and said, This is going to be a predominantly white school."

But Clemon, the former judge now working on Jefferson County's behalf, insists that making Gardendale predominantly white is precisely the point. One of the earliest supporters of this secession was Scott Beason, a former state legislator and radio host. Once, while wearing a wire for state investigators, Beason referred to African-Americans as "aborigines." A staunch nativist, Beason has promised to "empty the clip" on undocumented immigrants. (Beason did not respond to a request for comment; the Gardendale Board of Education declined, through Martin, to speak on the record. Gardendale's lawyers did not answer queries either.)

Another early proponent was Christopher Lucas, a local attorney who now sits on the city's board of education. As he and others were organizing the secession movement on Facebook, Lucas explained in an October 2012 posting what appears to have been a chief concern: "Would Gardendale be required to bring in minorities from outside of the municipal boundaries to achieve some sort of quota? No. The school system is for residents of Gardendale."

Although Gardendale High is under an integration order, it is only about 22.6 percent black, while the county is 43 percent black. Still, students can transfer within the county, and Gardendale is one of the few that afford minority students the opportunity to attend a majority-white high school. There are 26 of these "racial desegregation transfer" students at Gardendale High, accounting for 10 percent of its black population. About another 150 black students from across the county now take classes in Gardendale High's impressive vocational facilities.

The most profoundly whitening feature of the new system would be the exclusion of North Smithfield from Gardendale's schools. A small, unincorporated community 10 miles south of town, North Smithfield sends about 130 black students to Gardendale schools. When it first proposed secession, Gardendale excluded North Smithfield while including two other unincorporated areas, Mount Olive and Brookside, which are overwhelmingly white.

As the fight with Jefferson County intensified through late 2015 and into 2016, the newly formed Gardendale Board of Education decided to allow North Smithfield students to attend Gardendale schools. But the decision was made without consulting North Smithfield residents. North Smithfield students would attend Gardendale schools indefinitely, but North Smithfield would have no seats on Gardendale's board of education.

During the trial, a mother from North Smithfield testified it was plain to her that Gardendale would accept North Smithfield students only to satisfy the Stout order. The black students would be a token, discarded once no longer necessary. "They don't want black children there," she said.

Fiefdoms Funded by Public Dollars

Regardless of what happens in Gardendale, Birmingham and its suburbs are an example of what happens when communities diminish the scope of public education, creating their own fiefdoms, funded by public dollars but effectively functioning as private institutions that guard against intruders.

To cross from Jefferson County into Birmingham is to plunge into an educational ravine. Last year, a nonprofit called EdBuild released a report called "Fault Lines," about the most segregating municipal borders in America. Those borders are frequently created by suburbs that want to use their property taxes to fund their own schools, without having to share with poorer inner-city neighbors. In many ways, the explicit tethering of taxation to education is a major motivational factor for school secession movements, allowing citizens to act like dissatisfied customers and take their tax dollars elsewhere.

EdBuild called Jefferson County, with its 13 school districts, "a case study in gerrymandering" and branded the borders around Birmingham as the second-most segregating in the nation, after Detroit's. The Birmingham City system is 95 percent black and, according to one ranking, isn't even one of the 100 best school districts in Alabama, which has only 173 districts. Mountain Brook and Vestavia Hills, by contrast, are almost entirely white and the pride of the state. The borders that separate those two suburbs from Birmingham are, according to EdBuild, "among the nation's worst." Homewood and Hoover aren't much better.

Try to see this from the point of view of a Gardendale parent. If racial equality is so important, then why are those wealthy over-the-mountain suburbs exempt from it? Is integration only the job of working-class whites? Shouldn't the suburbs that have the most—Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills—be the ones required to share before those that have less? Thinking this way, a white parent in Gardendale is likely to reach a conclusion very similar to one reached by a black parent: The system is overwhelmingly, crushingly unfair.

Last winter, when community members were afforded the unusual privilege to comment before the court, one of those who spoke was Ralph "Skip" Lindsey III, who lives in Gardendale and has two children in the public schools. This is how he explained his support of Gardendale's secession: "I won't be satisfied unless I hear that all of the other schools that have come out of the county and out of every county system in the state are unwound…. You've got to unwind Trussville, you've got to unwind Hoover, you've got to unwind Leeds. You've got to do it all, or you can't do one."

A $55 Million School for Free

Craig Pouncey has the quiet solidity of late middle age, though there is a slightly elfin quality to his features, some last remnant of youth. His voice has the twang of the Deep South, but he grew up in Los Angeles. His family eventually moved back to Alabama, and he has lived there ever since, on the farm started in the 1940s by his grandparents. He has taught middle school and served as the chief of staff to Bice, the state school superintendent. Today, Pouncey is the superintendent of the Jefferson County school system, a position he has held since 2014. He gets back to the farm, outside of Montgomery, as often as he can.

He says the issue is fairness. The county built a new school to serve as a regional hub. Now, Gardendale wants to claim that school as its own. "I don't think [race] was a real driving force," he says. "The real driving force was the perception that they could get a $55 million high school for free."

Most schools in Jefferson County do not have facilities worth $55 million, or even $5 million. After lunch, Pouncey and I visited Fultondale High School, about 3 miles east of Gardendale High. At the entrance to the school, the principal peeled back a large gray doormat to reveal the letter N laid into the travertine. The symbol is a vestige of New Castle High School, an all-black school when it opened in 1965. The whole building is a vestige of that time, a structure of red brick and tan paneling that looks like a decommissioned bus station. Pouncey had hoped to combine Fultondale and Gardendale at the new Gardendale High School, but the secession movement has placed that plan in jeopardy.

During the trial, a lawyer for Gardendale, Stephen Rowe, questioned Pouncey about this proposal: "Have you considered that, if this plan is carried out, that now the Fultondale class president won't be a class president—they'll have to go to Gardendale, where they're a minority in a bigger school?"

Much of the hearing had a faintly surreal quality, like the exchange above, especially when Gardendale was forced to justify its desire for local control. Jefferson County was on stronger footing, since most statistical findings bolster its argument. The court heard testimony from Michigan State University scholar John Yun, who noted that black children who attended Gardendale Elementary showed "a very large jump" in both math and reading scores. If those students continued on to Gardendale High, they could presumably choose from the school's 12 Advanced Placement courses. Fultondale offers only three AP courses.

Yun argued that if Gardendale were to leave, Jefferson County would become poorer and blacker. It would have fewer resources, and its schools would be more crowded.

The hearing's most dramatic moment was when Haikala asked Martin, the Gardendale superintendent, if he'd ever read the Brown v. Board ruling of 1954. The question clearly caught Martin by surprise. He admitted that he had not read the Supreme Court decision "in its entirety," although he correctly identified the school district in question as being in Topeka, Kansas.

"I can't remember if it was Thurgood Marshall, or who, that argued that case," Martin said.

"I told you it's not meant to be a test," Haikala responded. The point was not to make Martin seem ignorant of the South's racial history, even though he also admitted, during his cross-examination, that he'd never hired an African-American, nor had he ever worked with African-American children.

Haikala asked about Brown v. Board to underscore the significance of the case before her, which was not about a single high school, nor a single town. It was about a thing we said we would do because we were a nation of free and equal persons. She wanted to know if we still aspired to that ideal, in Alabama, in Illinois, in California.

Impervious to Facts

There is another Jefferson County, in another Southern state, that has done things very differently than Jefferson County, Alabama. The one in Kentucky includes the city of Louisville and its proximal suburbs, and a school district that educates 100,000 children.

It does so in a rare big-city system that considers racial integration a crucial goal. And it has done so even after the U.S. Supreme Court's 2007 decision in the Parents Involved case, which forbade Jefferson County from using race as the determining factor for school assignments. The system's administrators came up with a formula that used socioeconomic status instead. While some students travel long distances on buses, the result is that the schools have remained racially balanced.

Donna Hargens, the system's superintendent, told me the push for diversity has to be combined with choice, so that parents don't feel as if they're being railroaded into integration. Magnet schools are "absolutely essential," she says, presumably because they signal a commitment to excellence; Hartford, Connecticut, also relies on magnet schools in its much-praised integration plan, which pulls in students from the wealthy white suburbs that surround the impoverished urban core. As a sign of enthusiasm for integration, Hargens cited the finding that 42 percent of parents do not choose the closest school for their children.

An equivalent system in Birmingham would combine the city system with Jefferson County, while dissolving long-standing islands of privilege like Mountain Brook and Vestavia Hills. But there is no political will for that, nor the political capital. The will is flowing the other way, in the direction of self-assertion. A less kind word for the trend is selfishness.

Last year, investigative reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote for The New York Times Magazine about choosing a public school in Brooklyn for her daughter, Najya. Hannah-Jones, who'd reported on school segregation for ProPublica, was relatively new to New York City. The city, which has never been under court order, has "the most segregated schools in the country," a study by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, found in 2014. That partly has to do with housing segregation, as well as the yawning disparity of resources to which that disparity inevitably leads.

Nor is there any more will to integrate in Manhattan than there is in Gardendale. Bill de Blasio, New York's progressive mayor, entered City Hall promising to redress the inequality, which he argued had been foisted on New Yorkers by his predecessor, billionaire Michael Bloomberg. But his schools chancellor, Carmen Fariña, said in February 2016, "I want to see diversity in schools organically. I don't want to see mandates." That means City Hall is too afraid of affluent white voters to wean them off their local schools.

Hannah-Jones had a choice between the highly desired P.S. 8, which is mostly white, and P.S. 307, which educates mostly children of color. White parents generally shun P.S. 307, but that was where Hannah-Jones sent Najya, because she felt it was her duty.

When I called Hannah-Jones, I wanted very much to know how Najya was doing at P.S. 307, whose test scores are notably lower than those at P.S. 8. "My daughter is doing wonderfully," she says. She notes that while she remains "very pessimistic" about the prospects for integration, the reaction to her article has given her "a tiny bit of hope."

Economist Tyler Cowen, who is a conservative, writes about P.S. 8 and P.S. 307 in his new book, The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream, calling white parents' visceral fear of a mostly black school "discouraging." He deems the fleeting integration in Brooklyn "a kind of temporary experiment in white lives, to be reversed once the next generation comes along." Hannah-Jones agrees. "You're gonna have to force and cajole people" into integration, she says, which is why the court orders of the 1960s and '70s proved effective. "We're not going to do this voluntarily." Integration has been shown to help both black and white children, but fears of racial mixing override fact. "There is still a deep-seated racial prejudice that white Americans feel towards black children," Hannah-Jones tells me. It pains me to agree with her.

Even Louisville's success is imperiled. A bill sponsored by a Republican state representative would effectively end cross-county busing, keeping kids in their neighborhood schools. But neighborhoods are segregated in Louisville, as they are pretty much everywhere in America. Without busing, there can be no integration.

Earlier this spring, the anti-integration bill passed in one of the state's legislative chambers but did not come to a vote in the other before the session's close. For now, the schools in Louisville remain integrated.

A Sturdy Barrier

Gardendale learned its fate in the middle of April, in a surprising ruling by Haikala. During the hearing that took place over the winter, she seemed consistently skeptical about Gardendale's claims that it can improve its schools only through local control.

She remained skeptical in the decision handed down last month, pointing out that many in Gardendale "prefer a predominantly white city." At the same time, Haikala acceded to Gardendale's wishes by allowing for a separation that would begin at the elementary level and take place over three years. She will supposedly monitor the process to make sure Gardendale commits to desegregation efforts. Among other provisions, she wants the Gardendale Board of Education to appoint a black member. Should the secession process continue apace, she will have Gardendale compensate Jefferson County for the $55 million high school.

"The Court is giving the Gardendale Board of Education an opportunity to demonstrate good faith," Haikala wrote, despite having demonstrated her own suspicion of Gardendale's motives from the bench.

"It's hard to square that the decision directly acknowledges race played a factor, but it still allows the district to move forward with its plans," says Monique Lin-Luse, an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund who represented some of the Jefferson County families that opposed the split.

Clemon, who argued the original Stout case, said he was "disappointed" by Haikala's findings. "Hope never dies, and the struggle continues," he told AL.com, echoing Ted Kennedy's famous dream-shall-never-die speech at the 1980 Democratic National Convention.

Shortly after returning from Alabama, I reached out to an old friend. About 10 years ago, Steve and I drove across the country together: He had just graduated from an Ivy League college and was on his way to a top-ranked law school on the West Coast. Steve, who is Jewish, grew up in Mountain Brook. We stopped there on our first night on the road. It seemed like a nice place. In the morning, we ate eggs and headed for Mississippi.

Today, Steve lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and works in finance. (He asked me not to use his real name because he doesn't think his employer would want him commenting for this story.) He is conflicted about Mountain Brook. The education was excellent, but it was still an Alabama education. In middle school, he was called a "nigger lover" by other students for refusing to participate in the taunting of black classmates. His family was liberal, from elsewhere. While his classmates spent the weekends hunting, Steve and his family would go to museums. "It's a great lifestyle if your family has been in Mountain Brook forever," he told me.

Today, Steve and his wife live in a part of Oakland called Rockridge. Although Oakland has traditionally had problems with crime, the city is so segregated that—as in Chicago or Brooklyn—you can easily occupy a comfortable reality in which gunfire will never intrude. A house in Rockridge sells for $1.3 million, double the median home price in Mountain Brook.

Schools, though, are a problem. Rockridge feeds into the Oakland Unified School District, which many white parents fear, particularly those with kids in the upper grades. I asked Steve what he will do when he has a child old enough to enroll in school. Will he and his wife stay in Oakland, or will they move "through the tunnel," to the vastly superior districts of Orinda or Walnut Creek?

Steve had to think about this. "I want them to be part of a diverse community," he said of the children he plans to have, then paused. What Steve said next we have all said, or thought, all of us who believe that sending a child to Stanford or Brown is proof of parenting done right. It is a small word, but a sturdy barrier between our ideals and our realities, the lives we should live and the lives we do.

"But…"