The 10-story block of flats on King's Road, Barking, could be anywhere in suburban London. Modern social housing with staggered metal balconies overlook a quiet residential street. The playful shrieks of children on their lunch break filter through from a nearby school. Residents leave their homes to get groceries or to walk their children on tree-lined sidewalks.

But the Elizabeth Fry Flats—named after the 19th century British social reformer known as the "Angel of Prisons"—harbored a peddler of death in London's East End: Khuram Shazad Butt.

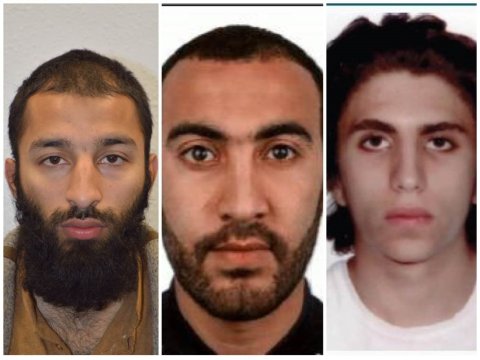

The 27-year-old British national of Pakistani descent—who also went by the name Abu Zaitun, or "Abz"—led a three-man jihadi cell on Saturday night that killed seven people and maimed dozens in a vehicle and knife attack initiated on London Bridge. Police shot dead all three men within eight minutes of the first emergency call outside the Wheatsheaf pub in nearby Borough Market.

Outside Butt's apartment building, a five-minute walk from Barking's bustling high street, three police vans remain stationed as authorities continue to investigate the motivations for the horrific attack claimed by the Islamic State militant group (ISIS), the third in as many months on British soil. Residents peer from their balconies, filming a club of gawping journalists stationed outside.

This is where Butt lived with his wife and two children, one a toddler and the other a newborn. British police named him and his accomplice Rachid Redouane, 30, of Moroccan and Libyan descent, on Monday evening. On Tuesday, they named the third attacker as 22-year-old Italian-Moroccan dual national Youssef Zaghba. Butt was on the radar of Britain's domestic security service, MI5, before Saturday's attack, but Redouane was not, according to police.

Details have not yet emerged about how the men planned their attack—besides their hiring of a rental van beforehand—but it's clear that the three shared a desire to kill and maim innocent people in the name of their warped version of Islam. And two of them came from Barking. Police arrested another man from Barking, a 27-year-old, on Tuesday in connection with the attack. Zaghba also resided in east London, although it remains unclear where.

The suburb of Barking, home to 76,000 people, has undergone one of the most rapid transformations in London's recent history and has become a flashpoint for two kinds of violent extremism: the white far-right, and the radical Islamists.

A neighbor of Butt, 32-year-old Raza Sheikh, expresses shock that the plot that shook the British capital last week may have been hatched on his street. "We are very upset. We can't describe the feeling when you have someone in your neighborhood that has done this. He could have committed this kind of act here," says the private security guard, a Muslim of Pakistani descent who lives just a few houses along from the attacker's apartment with his two brothers. "Personally I don't know this guy, but he was misguided. The disturbing thing is that they use the name of Islam. It is not Islam."

Barking is "a mixture of cultures," Sheikh says. "You can find any community here. English, Asian, Eastern European, African." Barking has now become a town that epitomizes British multiculturalism. Census data shows that 80 percent of Barking and Dagenham identified as white British in 2001; a decade later, this dropped to 49 percent in what the British press dubbed a "white flight."

Many Londoners have embraced multiculturalism's economic, cultural and societal benefits—and, on the surface, Barking appears to have a strong community spirit. But the departure of the traditionally white working-class 'East Enders' has left rifts between polarized, more conservative sections of society trying to hold on to their own visions—whether nationalist or Islamist.

The far-right British National Party (BNP) and radical Islamist preacher Anjem Choudary's now-banned Al-Muhajiroun—responsible for what security services say is the radicalization of hundreds of British Muslims, and of which Butt was a known supporter—have jostled for influence on the fringes of society here. Both have held marches through the town, and the core supporters of Choudary—who is serving five years in prison for supporting ISIS—used to live in nearby Ilford, where police raided a property on Tuesday morning. A British court in 2015 sentenced a Muhajiroun supporter, 18-year-old Kazi Islam, to eight years in prison for grooming a teenager with Asperger's Syndrome, whom he met at Barking and Dagenham college, into attempting to build a pipe bomb and hack a British soldier to death with a kitchen knife or meat cleaver.

But what Molenbeek is to Brussels, or L'Ariane to Nice—de facto Muslim ghettos—Barking is not to London. It is rather defined by the diversity and poverty of the area, which is immediately clear as soon as you step out of its subway station.

Gentrification has shot east in London, with the middle-class moving into what were once some of the poorest areas in the city, such as now hipster-filled Hackney and Dalston. But this has not yet touched Barking, despite it being just five miles from the gleaming skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, one of London's main financial districts. The town has the highest level of unemployment, second highest number of homelessness claims and second-lowest male life expectancy in the capital.

Along Barking's high street, shuttered stores daubed with graffiti sit alongside thrift stores, betting shops and barbers. Men drink cans of beer on the street. People collect their social security cheques from the job center, while the homeless ask for change and others sit their day away on benches. The lack of economic opportunity alone does not drive young people to extremism, but experts have long emphasized that those who feel the most hopeless in society are among the most vulnerable to radicalization.

"We are really tolerant of each other"

But on Barking's main street, there's more than just a lack of economic opportunity. The smell of fried chicken from the many bright fast-food spots collides with the whiff of Middle Eastern kebab joints. Turn a corner and you meet a halal butcher's, around the next are Lithuanian and Romanian supermarkets. Muslim women wearing niqabs, Islamic full-face veils, walk alongside women in West Ham United Football Club jackets.

"We should live in a cesspit. We are in the middle of it," says Ash Siddique, secretary of the gated Al-Madina Mosque, referring to nationalist and Islamist extremists. "But the reality is, we don't. We live in a borough where actually we are really tolerant of each other, we get on really well with each other."

Siddique's mosque—Barking's largest, with a daily footfall of a thousand people and 3,000 for Friday prayers—serves as a "beacon" for others on how to run their place of worship, he tells Newsweek in an interview at his office. It offers counseling services to disenfranchized Muslims and keeps a close eye on potential radicalization of its members, looking out for anti-British sentiment or violent intentions. Siddique and his team run karate classes, welcome the homeless in every month—and monitor worshippers to prevent radicalization (and suggest mentors who try to help individuals heading down the wrong path). Not everyone appreciates his moderate message of tolerance and peace: Several more radical Muslims, who he calls the "bad guys," have sometimes left his mosque and never returned.

But Siddique, who says a congregation of 1,000 Muslims at the mosque prayed immediately on Saturday night for those killed in the attack, acknowledges there is a problem that moderate sections of London's Muslim community are not recognizing: young Muslim men and women who feel they do not belong.

"I feel some Muslim communities have failed. We have stuck our head in the sand," he says. The community, he says, needs to acknowledge that there are young Muslims who suffer the same "ills" as other sections of society: drugs, sex outside of marriage and crime. "We judge those youngsters and push them to the boundaries. Who are they going to go to? You have a vulnerable individual whose life isn't going anywhere, who is then groomed by someone who knows what they need—an arm put round them. They are going to walk to the other end of the earth for [the recruiter]."

Other neighbors of Butt described him as a normal, sociable young man. He attended barbecues with neighbors, watched his beloved Arsenal Football Club and trained at the Ummah Fitness Center, a first-floor gym a short walk from the Al-Madina Mosque. But he also posed with the Islamist black-and-white Shahada flag in Regent's Park in 2015 with other Muhajiroun-linked Islamists. He is also reported to have spent time playing football with teenage boys, in Barking's parks, but also promoting radical versions of Islam, according to one neighbor and another who reported him to authorities. Whether he was directly involved in radicalizing other young Muslims remains unclear.

Read more: London attack survivor recounts near-miss as car rammed civilians on Westminster Bridge

Siddique also blames Britain's security services for the attack, since at least two people say they notified authorities of Butt's increasingly extremist views long before it happened: once in 2015 for attempting to indoctrinate children, another for accessing online propaganda. "People did their job. They told the authorities," he says. "Years later he kills innocents, and people ask the question 'what is the Muslim community doing about it?'"

Butt was also in the public eye, starring in a British documentary about radical Islamists in London, entitled "The Jihadis Next Door," which Siddique slams as an easy "propaganda tool" handed to them by the British media. He appeared with friend Abu Rumaysah in the film, a jihadi who traveled to Syria to become one of ISIS's main English-language propagandists.

Siddique guesses that Butt attended a more radical mosque in Barking that he would not even be allowed to enter, likely tucked away in a shopfront or a house. "The one he went to will be of a particular belief system," he says. "The answer will be that he was a misfit. Somebody has got hold of him and said your life is about this."

In fact, Butt was kicked out of two East End mosques for his views: the East London Mosque and Barking's Jabir bin Zayd Islamic Center, after he repeatedly interrupted its imam by shouting "Only God is in charge," according to Salaudeen Jailabdeen, who lived near Butt. As Butt became more extreme, the Muslim community who knew him seemingly tried their best to stop him. Even his adoption of the name Abu Zaitun was a clear sign of his more radical beliefs. Abu translates as "father of" in Arabic and is taken on by many jihadis as a "nom-de-guerre," including the world's most notorious—ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. "If you are using the name Abu in a place like Barking then you know there's a problem," says Siddique.

"Leave religion at the door"

Some in Barking have launched non-religious efforts to help disenfranchised young people turning to a path of crime or violent jihadism. At the TKO Boxing Gym, on an adjacent sideroad to the town's main thoroughfare, 59-year-old Johnny Eames is running free boxing classes for the community's children and teenagers out of a sports complex that also hosts a food bank.

Its green glass door is cracked, the donated gym equipment is rickety, and it hasn't received any funding from local authorities yet. That's typical of what Barking residents say is a wider neglect by both the British government and local authorities, but the gym still offers young people hope, says Eames, a promoter and trainer of former European boxing champions such as Billy-Joe Saunders and Kevin Mitchell, who works for free alongside four other voluntary staff.

"I've got Albanians, Afghanis, Chinese, Jamaicans, Africans, Irish travelers, Romani [people]. Probably the only true Englishman in here is myself," he laughs, sitting on the edge of the gym's smaller, red boxing ring. He says he tells his boxers to "leave religion at the door," whether Islam or Christianity, to keep the gym focused on boxing. Visibly angry about the London attack, he says jihadi recruiters should be "hung."

Eames, an ex-prisoner who lives in East Ham, another nearby working-class area of London's East End, only set up the gym two months ago. "I never realized how poverty stricken Barking is. It has opened my eyes," he says. "Our aim is to show the kids round here a different way. This place can help if the council help us." His fellow trainer, 41-year-old Irishman Stephen Mannus-Dunbar, interjects: "This is the perfect thing for Barking."

The underlying tensions in Barking represent a wider political battle taking place in Britain. Like much of the country, Barking voted to leave the European Union in last June's referendum. Despite having two opposition lawmakers from the center-left Labour Party, many locals view Barking and its neighbor Dagenham as areas of marked support for the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP), a Euroskeptic, anti-immigration movement.

UKIP is targeting the towns as key seats to win in Britain's general election on Thursday, exploiting insecurity in the area over jobs, immigration and housing given to migrants from inside and outside the EU.

This far-right support has spilled over into attacks on the Muslim community. Siddique says women at his mosque have had people spit on the backs of their robes as they walked down the street. In 2013, two white women repeatedly punched a Somali woman wearing a hijab, describing her as a "Muslim terrorist" after their children argued over swings in a local park. Hate crimes against Muslims nearly tripled in Barking between 2014 and 2015, from 8 to 21, according to London police figures. Since the Paris attacks in November 2015, Siddique says many members of the community tell him they do not want to report crimes to the police out of fear they would be ignored.

Mary Phillips, 46, a local housewife and mother of six, is less pessimistic about social cohesion in Barking. She says the issue of radical Islamists in Barking is limited to "idiots" and that if Barking has changed in any way, it's for the better. She says her six children "love" the area, and "that's all that matters" to her. Alan Harris, a 70-year-old retiree, says "it's changed a lot but I haven't felt any tensions here." For all of its fractures, Barking voted the far-right BNP's 12 councillors out of its local authority in the 2010 local elections after it elected them in 2006.

But there are signs that nationalism and underlying prejudices in the white British community will remain. John, a 27-year-old laborer who declines to give his last name, points to his apartment block that sits near Bobby Moore Way, named after England's 1966 World Cup-winning captain. "I'm the only one who speaks English up there. They're all on the dole and the kids are tearaways," he says, referring to families who receive social security payments.

Tommy, a 67-year-old retiree who declines to give his last name as he has a lunchtime drink at the local pub, The Barking Dog, laments the boarding-up of the town's pubs, which have dwindled from 15 to just four in recent years. "They had to close because of the community. It used to be a lovely town, but now there's too many foreigners," he says.

The pensioner apologizes if his answer sounds racist, and qualifies it by saying lots of members of Barking's minorities are "lovely people." But, as he takes a draw on his cigarette, looking out onto Barking's main street, he becomes emotional. He says he fears for the future of his children and his grandchildren. He worries about the extremist threat, about his town changing. For Tommy, is there anything left to love about the place he has lived in for more than thirty years? "Not anymore, no."

While Siddique speaks of unity between Barking's religious circles—its Christians, Muslims, Jews—the divisions between the white and conservative Muslim communities here may widen further in the aftermath of the latest attack in London. For a city with the first Muslim mayor of a Western capital, and one that has long celebrated its diversity, that could be the worst outcome of all.