If you want an ominous warning about the impact of the Trump era on Silicon Valley, look at a former American behemoth of innovation: Detroit.

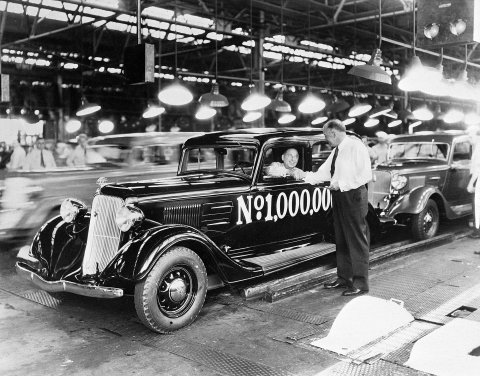

By 1908, when Henry Ford started building the Model T in a factory there, the automobile was the most important new technology in the world. The industry coalesced in and around that city as inventors and investors rushed to the region. Out of a torrent of startups—Cadillac Automobile Co., Dodge Brothers, Durant Motors, Mercury Cyclecar Co.—a few global monoliths emerged and consolidated. For the next four decades, Ford, General Motors, Chrysler and the city's car-making ecosystem dominated every aspect of the global auto industry—and, for that matter, the U.S. economy. Charles Wilson, who was the president of GM before becoming President Dwight D. Eisenhower's secretary of defense, coined the phrase "What's good for General Motors is good for the country."

The end of the 1960s turned out to be Detroit's apex. In the early 1970s, dubious U.S. economic and foreign policy led to disaster when the Middle East OPEC nations initiated an oil embargo. Gas became scarce and expensive, and Detroit was caught focusing on the wrong products—ostentatious gas-guzzlers—at the wrong time, giving Japanese makers of small cars an opening in the U.S. market. Pulitzer Prize–winning auto historian Joseph White wrote about two fateful mistakes that made things worse. First, "Detroit underestimated the competition," he said. The likes of Toyota and Honda had become much more adept than industry executives realized. Second, the U.S. companies "handled failure better than success." Detroit's decades of triumph set up the hubris, waste and bad practices that came to haunt it.

From there, it was a short trip to loss of market leadership, layoffs, plant closings and a city that fell into a desperate decline.

Think that could never happen to Silicon Valley? Like 1970s Detroit, Silicon Valley seems to be handling success rather badly. Look at the twisted mess at Uber and the culture wars tearing at Google's guts. Insanely high valuations of private companies are starting to look like a perilous pyramid scheme Bernie Madoff might admire. High costs and ever-worsening congestion are making the San Francisco Bay Area nearly unlivable for all but the superrich. At the same time, much of U.S. tech is underestimating the competition, particularly from China and the European Union.

Making it all worse, the Trump administration seems to be doing everything it can to help shove Silicon Valley off its pedestal. Trump's policies on trade, immigration and investment are giving competing nations openings to steal important chunks of Silicon Valley's global leadership, lure away talent and divert capital to other rising tech centers—even France. (You know, the country President George W. Bush once said doesn't even "have a word for entrepreneur .")

Related: Is the Silicon Valley Bubble about to Pop?

The Silicon Valley tech industry isn't going to suddenly crumble and vanish. Detroit's auto industry didn't disappear either. But there's a clear demarcation point in the early 1970s, when Detroit's worldwide hegemony ended. The CEOs, founders and wizards of Silicon Valley would be misguided to think they're immune from any similar stumble off their pedestal.

The Un-American Dream

I first met Stepan Pachikov in Moscow in 1991. He had founded ParaGraph, one of the first private software companies in the collapsing Soviet Union. ParaGraph had developed a way for computers to recognize handwritten words—not easy in those days. Apple ended up licensing the software for its ill-fated Newton, a handheld PDA. Before 1991, a citizen of the USSR could barely dream of working in Silicon Valley. "The major obstacle between me and the world was the Soviet Union," Pachikov once told me. When the Soviets could no longer keep their people from leaving, Pachikov bolted for the most dynamic technology center on the planet, moving his company and his family to the Bay Area. In 1997, he sold ParaGraph to Silicon Graphics for $50 million.

A few years after, Pachikov built on his knowledge of character-recognition software and founded a company you've probably heard of: Evernote. Based in Redwood City, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley, Evernote makes a productivity app and has around 400 employees. It has raised 10 rounds of funding from 15 investors, including top-tier venture company Sequoia Capital. The story is Silicon Valley at its best: lure great innovators; make capital available; let the startup draw from a local milieu of the best engineers, coders and MBAs; and watch as the enterprise moves the world ahead a few steps.

Fast-forward a couple of decades. Included in the family that Pachikov moved to the U.S. was a son, Alex, now 37. Alex Pachikov recently started Sunflower Labs, a company that marries artificial intelligence and drones to create a new kind of home security system. But to him, the tech scene looks different from the one his father embraced—it's now spread across the globe. "My R&D office is in Zürich," he says. "My industrial design, graphic design and PR are in San Francisco. One of my investors-advisers is in Tokyo. Our manufacturing will be in China and Taiwan. Getting all the time zones right is a challenge."

The arc of the Pachikovs suggests that Silicon Valley, once the center of the tech universe, is now just one star in a constellation. Alex Pachikov's company-creation story is becoming more common. Tech investor Andres Barreto said he has six companies incubating inside Y Combinator in Silicon Valley, "but their engineering teams are all in Latin America or they are starting to build teams in Latin America." The transition is reflected in tech job listings in Silicon Valley, down 5.9 percent the first half of the year, according to jobs site Indeed. The trend shows up in the number and kinds of companies started. The region's seed and angel investors completed about 900 deals in the second quarter of 2017, down from 1,100 the same quarter a year before, according to a PitchBook report, while company creation is climbing globally.

Famed tech analyst Mary Meeker noted that 60 percent of the most highly valued U.S. tech companies were founded by first- or second-generation Americans. Those companies employ 1.5 million people and include Apple, Alphabet, Amazon and Facebook—four of the most valuable companies in America. Imagine the long-term impact if more would-be immigrants to the U.S. launch their startups from wherever they are now—if the likes of Stepan Pachikov don't make the journey. The implications are enormous for the U.S. economy, and it could affect America's position in the world. The U.S. projects its culture and values through its tech exports. Billions of people globally are on Facebook, use iPhones and rely on Google—all made in America. The next generation of technology, coming from nations other than America, might look and feel different.

The Un-Unicorn

If Silicon Valley's dominance wanes, it will be in part because of what it's doing to itself, and what is being done to it by Donald Trump.

Remember all the fuss last year about the explosion of tech " unicorns "—those privately held billion-dollar companies? The financial trap behind that trend is threatening Silicon Valley's company-building model.

Because of U.S. regulations and shifting attitudes in the tech industry, successful startups are staying private. Initial public offerings used to be a common way for emerging companies to finance growth, but in 2016, according to a new paper by investment startup Urgent International, just 18 U.S. companies completed IPOs that raised less than $50 million, compared with 557 companies in 1996. In other words, within 20 years, an important path to expansion for small, fast-growing Silicon Valley startups has been blocked. Instead, companies rely on rounds of private financing, which inflate or muddle valuations, leading to unicorns that shouldn't be unicorns. Urgent has a plan to exploit Silicon Valley's IPO problem: It is proposing a way to take U.S. companies public on other stock exchanges around the world. "It's a huge opportunity for us as a fund amid a travesty for U.S. tech companies," Urgent's Jeff Stewart tells me.

The financial mess in Silicon Valley is writ large in the turmoil at Uber. Founder Travis Kalanick, who was ousted as CEO but remains Uber's chairman, refused to consider taking Uber public. He also raised huge round after huge round of private financing, so Uber is now valued at $70 billion—more than Ford or GM. Yet, at some point, the company will run out of "greater fool" investors who will put up funding at even higher valuations, limiting Uber's ability to raise money. New CEO Dara Khosrowshahi says Uber may go public around 2020, but public markets might value Uber lower than the private valuations, which would mean big losses for Uber's private investors.

This tension over an IPO was at the heart of why one of Uber's main investors, venture company Benchmark Capital, sued Kalanick in a struggle to control the company, making for a mind-jarring scenario: one of the most successful tech VCs suing one of the most successful company founders—an epic Silicon Valley equivalent of Brutus turning on Caesar. In fact, Uber investor and Kalanick supporter Shervin Pishevar unleashed in August a Shakespearean tirade aimed at Benchmark: "Let our just cause give pause to those who would ever dream of ever emulating the shameful shenanigans of these sanctimonious hypocrites," he fumed. You don't often see that in business circles.

At the same time, issues of sexism and discrimination are sullying Silicon Valley's self-image as a land of opportunity for all. At Google, low-level engineer James Damore wrote an anti-diversity manifesto that went viral and challenged the leadership of CEO Sundar Pichai. A book by Ellen Pao, who famously sued venture capital giant Kleiner Perkins for sexual discrimination, just came out, squirting more lighter fluid on that issue's hot coals.

In another ring of the Silicon Valley circus, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has been slamming Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, mocking his knowledge of AI as "limited" after Zuckerberg accused Musk of making "irresponsible" comments about AI being dangerous to humanity. This would be as entertaining as watching Bugs Bunny debate duck season vs. rabbit season with Daffy Duck, except it reflects a growing and sometimes hostile divide in tech over whether AI needs to be tamed or let loose.

Most damaging of all may be the policies of the Trump administration, which has been implementing or proposing one policy after another that puts the industry at a competitive disadvantage.

Earlier this year, the president initiated a review of H-1B visas for foreign workers, which tech companies rely on to bring in talent. More recently, the Trump administration delayed —and may kill—the International Entrepreneur Rule, which would make it easier for foreign company founders to bring their startups to the U.S. "At a time when countries around the world are doing all they can to attract and retain talented individuals to come to their shores to build and grow innovative companies, the Trump administration is signaling its intent to do the exact opposite," said Bobby Franklin, president and CEO of the National Venture Capital Association.

And in early September, Trump said he will end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which has allowed undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children to stay. Now, they may be deported. Some are valuable employees of tech companies. Microsoft pledged to pay the legal expenses of any employees who face deportation as DACA ends. Microsoft President Brad Smith called Trump's decision "a big step back for our entire country," and the industry worries that it will further discourage talented foreigners from coming to the U.S.

Other countries have started pursuing international talent like sharks circling surfers at dusk. "I myself hope that many of these engineers will come to China to work for us," said Robin Li, CEO of Chinese tech giant Baidu. Canada's minister of innovation, Navdeep Bains, launched a recruitment program, saying, "We want to be open to people." French President Emmanuel Macron announced that tech talent can "find in France a second homeland."

Even more detrimental to U.S. tech are two other Trump decisions: pulling out of the Paris climate accord and dumping the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement on trade with Asia.

Clean energy technology and innovations that solve climate change will be among the greatest business opportunities of the next two decades. Trump signaled that the U.S. won't welcome new energy innovations, which, again, clears the way for overseas competitors and makes it less likely American companies will develop energy solutions for their home market. A Trump America will just keep mining coal nobody else wants.

As political pundits point out, abandoning the TPP decreases the leverage for U.S. companies in the exploding tech markets in Asia and instead hands those opportunities to China's ever more powerful tech industry. The U.S. has nurtured monoliths like Apple, Google, Facebook and Netflix. But China's big three tech companies—Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent—are chasing down Silicon Valley much the way Toyota, Honda and Nissan reached out from Japan in the 1970s and sucker-punched Detroit. Alibaba and Tencent are already more than twice as valuable as Intel or IBM.

The Un-Intelligent Approach

For decades, the home market has been one of the great advantages to starting a tech company in the U.S. Nowhere else on earth could you find a single market with so many people with means hooked to the internet.

China now has nearly 750 million internet users, more than double the size of the entire U.S. population. India, with 1.3 billion people, boasts the fastest-growing internet population, now at about 300 million, and it still has less than one-third of its people connected. So Silicon Valley's advantage of a big home market for launching products is over.

How about its advantage in scientific research and technical wizardry? That's looking shaky as well.

The Chinese government is investing in a national AI plan, spending billions of dollars on research and startups. A report last October from the Obama administration found that China overtook the U.S. as the world's most prolific producer of research papers in deep learning publications sometime in 2013. (Deep learning is a type of machine learning.) And the gap continues to widen. China's vice minister of industry and information technology, Liu Lihua, reported that China has applied for 15,745 AI patents. A report by American consulting company PwC predicts that by 2030 AI-related growth will increase global gross domestic product by $16 trillion, and nearly half of that growth will accrue to China.

The key to creating the best AI is being able to feed it massive amounts of data from the ongoing behavior of users. The AI learns from the data and gets better. In that realm, whoever has the most and best data usually wins. Now that China has two or three times more users just in its home market, it will have the most data by a big margin.

China's tech companies attracted a record-high $56 billion in disclosed investments last year, according to Tech in Asia. Beijing-based Didi Chuxing, China's Uber-like company, has raised about $10 billion and bought Uber's Chinese operations last year after Uber realized it could not compete in that country.

At least the burgeoning Chinese startup scene may have woken up Silicon Valley. In September, a major San Francisco tech conference, TechCrunch Disrupt, will give over its main stage to interviews with top tech companies from China, including bike-sharing company Ofo, education startup VIPKid and investment company ZhenFund.

And if you want a fun fact with spooky historical echoes, consider that Chinese companies will be making 49 of the 103 all-electric cars expected to be on the market in 2020.

While China will throw up the most likely challengers to Silicon Valley, dozens of other countries are right behind it. For years, other nations have tried to emulate Silicon Valley, even adopting some version of its name, like Silicon Roundabout in London. Now, countries are increasingly playing to their cultural and market strengths while pointing to the dysfunctional political climate in the U.S. and the high cost of running a company in Silicon Valley. "I want France to attract new entrepreneurs, new researchers and be the nation for innovation and startups," France's Macron told CNBC. He has taken bold positions that stand in contrast to the U.S., like laying out a plan to ban fossil fuel cars by 2040.

Finland now hosts the highest-profile startup conference outside the U.S., called Slush. It attracts 20,000 people to Helsinki in December, when nobody should want to be in Helsinki. Canada has a growing AI community and committed $100 million this year to develop AI companies, and Canada is home to D-Wave, the best-known startup working on the difficult but potentially world-changing technology of quantum computing. Israel spits out 1,000 startups a year and ranks second in the world in innovation, behind Silicon Valley, according to the World Economic Forum.

The fact that technology companies get created all over the globe is not new. But the momentum has shifted. Silicon Valley and its sister U.S. regions—Seattle, Boston and Austin, Texas—used to win all the time and march their software and services out to every corner of the planet. Today, that kind of total victory is not so certain.

It's possible the momentum shift is temporary. Maybe the developing cultural backlash in Silicon Valley will root out discrimination, and Trump's immigration stance will get reversed, and the world's talent will again dream of working in an open office in Atherton, California. Maybe a financial downturn will reset tech's business practices and make America sane again. Maybe all that will happen before it's too late, and Silicon Valley will prove resilient.

"My reading is optimistic," says Enrico Moretti, author of The New Geography of Jobs and a University of California, Berkeley, professor. "Current administration policies, however incompetent, aren't likely to make a big dent on the concentration of technology jobs and firms in Silicon Valley, at least for the next five to 10 years." Yet, Moretti notes, it's likely that Silicon Valley will find itself in a new era of sharing the tech industry with others.

No one in the late 1960s would've thought Detroit was going to have to face a harsher future. In 1965, GM, Ford and Chrysler sold 90 percent of the cars on America's roads, according to Ward's Automotive. That's now down to about 40 percent. So in years to come, don't be surprised if you're in Kansas City or Phoenix or Baltimore and you get a ride in a Didi while using apps from Tencent. You might even, if things get really crazy, depend on software from some company in France that was started by someone the French might call an entrepreneur .