This is a painful story for me to write.

For a quarter of a century, I was a major part of the conservative movement. But like many on the right, in the wake of Donald Trump's victory I had to ask some uncomfortable questions. The 2016 presidential campaign was a brutal, disillusioning slog, and there came a moment when I realized that conservatives had created an alternate reality bubble—one that I had helped shape.

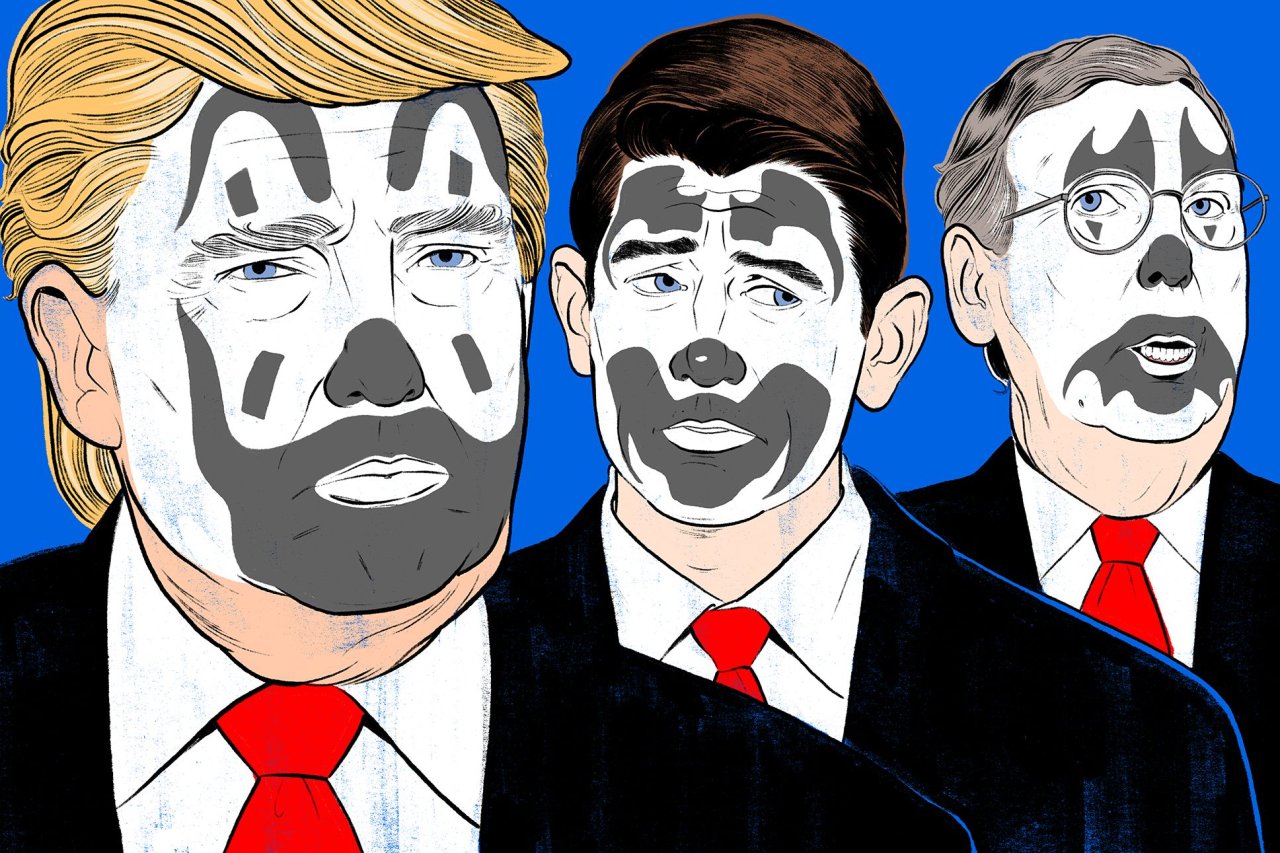

During the 2016 election, conservatives turned on the principles that had once animated them. Somehow a movement based on real ideas—such as economic freedom and limited government—had devolved into a tribe that valued neither principle nor truth; luminaries such as Edmund Burke and William F. Buckley Jr. had been replaced by media clowns such as Ann Coulter and Milo Yiannopoulos. Icons such as Ronald Reagan—with his optimism and geniality—had been supplanted by the dark, erratic narcissism of Donald Trump. Gradualism, expertise and prudence—the values that once were taken for granted among conservatives—were replaced by polls and ratings spikes, as the right allowed liberal overreach in the Obama era to blind them to the crackpots and bigots in their midst.

Some have argued that the election was a binary choice, that Hillary Clinton had to be defeated by any means. I share many of their concerns about Clinton, but the price was ruinous. The right's electoral victory has not wiped away its sins. It has magnified them, and the problems that were exposed during the 2016 campaign haven't disappeared. Success does not necessarily imply virtue or sanity. Kings can be both mad and bad, and the courtiers are usually loath to point out the obvious—just look at Caligula or Kim Jong Un.

Today, with Trump in office, the problems of the right are the problems of all Americans. And the worst part of it is that we—conservatives—did this to ourselves.

Donald Trump is the president we deserve.

Off the Wall

There was a time when we deserved better. And had it too.

On June 12, 1987, President Reagan was in West Berlin to deliver a powerful message to the evil empire, the USSR. His Soviet counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev, had branded himself as a benign peacemaker, and Reagan wanted him to prove it. More than two decades earlier, East German Communists had erected the Berlin Wall to keep defectors from fleeing the eastern part of the city, and the barrier remained, physically and symbolically dividing the two sides. With two panes of bulletproof glass separating him from a crowd of roughly 20,000, Reagan stood with East Berlin's Brandenburg Gate behind him and uttered the words that have come to define part of the greatness of his presidency. "If you seek peace," Reagan said, "come here, to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall."

The speech was vintage Reagan. His words championed freedom and unity, capitalism and strength. He saw America as "a shining city upon a hill," as he put it in a later speech, an ebullient description that captured the source of his popularity. And though he personified much of what conservatives loved about America—our positivity, grit and determination—Reaganism was always about the country, not the man. He was our president, not our "dear leader."

Almost three decades after Reagan's speech in Berlin, Trump delivered a very different message in Manhattan. On June 16, 2015, he made a dramatic entrance at Trump Tower, descending into the lobby on an escalator to the sounds of Neil Young's "Rockin' in the Free World." And with the cameras rolling, the reality-TV star announced he was running for president. The country was in real trouble, he said, in part, because Mexicans are sneaking across the border. "They're bringing drugs," he snarled. "They're bringing crime! They're rapists!" There was only one solution, Trump explained: "I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words."

With anger and bravado, Trump had declared war against Reaganism (the Gipper had been pro-immigration too)—and some people loved the brash new candidate for it.

This shift took many by surprise. In the 1980s, after Reagan became the face of the right, conservatives seemed like a united, monolithic force (especially to liberals who never really listened to what we had to say). The truth is, we have long been a jumble—a contentious collection of disparate, often querulous factions: libertarians, evangelicals, traditionalists, chamber of commerce types. As far back as the 1950s, there have been deep fissures in the movement. We called ourselves conservative, but supported the creative destruction of capitalism; we championed limited government, but also traditional values. We were the party of freedom, but also national security, law and order.

Over the past 50 years, conservative leaders had sought to knit together those ideological strands. It hasn't always been easy. In the 1960s, Buckley, the conservative author and founder of the National Review, went to war with both the far-right libertarian writer Ayn Rand and the extreme anti-Communist crackpots at the John Birch Society. Those divisions and others carried over into the Richard Nixon era in the 1970s. It wasn't until the early 1980s that Reagan managed to control these contradictions with a combination of charisma and competent governance.

Trump, however, exploited such divisions for his own gain. He tapped into something disturbing that we had ignored and perhaps nurtured—a shift from freedom to authoritarianism, from American "exceptionalism" to nativism and xenophobia. From his hard line on immigration and rebuttal of free trade to his strange fascination with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Trump represented a dramatic repudiation of the values that had once defined the movement.

If Reagan were alive, he would hardly recognize his party—or the walls it had erected.

Birther of a Nation

In between Reagan and Trump, there were signs of deep dysfunction in the conservative ranks, moments when the right seemed on the verge of losing it—from outbursts of anti-Semitism during Pat Buchanan's unlikely surge in 1992 to Sarah Palin's embarrassing ascendancy to the GOP ticket in 2008.

But the real turning point came with the election of Barack Obama and the rise of the Tea Party. While many of its discontents can be traced to the Bush years—Medicare Part D, changes to immigration policy and the big-bank bailouts—the Tea Party did not gain traction until after Obama's victory. The timing fueled suspicion that the movement had more to do with the new president's race—and party affiliation—than his policies, yet the early days of the Tea Party defied easy categorization. Despite the caricatures and repeated attempts by the left to portray them as dangerous or bigoted, Tea Party rallies were generally orderly events—and extraordinarily diverse. As the writer John Avlon put it in his book Wingnuts: Extremism in the Age of Obama, attendees at a typical rally included "libertarians, traditionalists, free-marketers, middle-class tax protesters, the more-patriotic-than-thou crowd, conservative shock jocks, frat boys, suit-and-tie Buckley-ites and more than a couple of requisite residents of Crazytown."

The Tea Party soon became the face of the conservative movement, firing up a base that had been defeated and demoralized. As Avlon noted, the movement marked an aggressive shift in tactics, as some conservatives decided to "mimic the confrontational street theater of the far left they had spent decades despising. Civility was the first calculated casualty." At rallies, signs comparing Obama to Hitler began popping up (as they had on the left with George W. Bush), while literature appeared skewering "Obama's Nazi health plan." Legitimate concerns over rationing health care morphed into overheated rhetoric about "death panels." All of this was dramatically accelerated by the rise of a perpetual outrage machine that included scam PACs and even the venerable Heritage Foundation, pushing the GOP into increasingly extreme and untenable positions, which ultimately led to a futile government shutdown.

Few on the right pushed back against these excesses. "In this environment," Avlon noted, "there are no enemies on the right and no such thing as too extreme—the more outrageous the statement, the more it will be applauded." Even after Representative Joe Wilson was censured for yelling "You lie!" at Obama during a speech on health care in 2009, many on the right hailed the South Carolina Republican as a hero.

In the lead-up to the 2012 presidential election, this shift toward vulgarity and bluster accelerated. But perhaps the defining moment occurred on March 23, 2011, when Trump made an appearance on The View. Few at the time thought he had a real interest in—or shot at—the presidency. But polls indicated he was popular, and he was flirting with the idea. Wearing his trademark dumpy blue suit and long red tie, the New York real estate mogul launched into what today feels like a typical stump speech. "We're not going to be a great country for long if we keep going the way we're going right now," he said. Trump was friendly and cordial, cracking jokes and holding Whoopi Goldberg's hand. But when the conversation turned to Obama, it grew heated. "Why doesn't he show his birth certificate?" Trump whined. "If you're going to be the president of the United States…you have to be born in this country."

The birther canard—that Obama was born in Kenya or somewhere abroad—didn't start with Trump. (And despite his false claims, it didn't start with Hillary Clinton either.) But perhaps more than any other figure, Trump proliferated birtherism, took the lie from the lunatic fringes of the internet and brought it to the mainstream. After his appearance on The View, he went further, implying to Laura Ingraham, the conservative commentator, that the president might secretly be a Muslim. After Obama produced his birth certificate in April 2011, Trump briefly acknowledged his legitimacy, then quickly seemed to recant, saying that "a lot of people do not think it was an authentic certificate." In doing so, he soaked up some much-desired publicity, which arguably helped him launch his 2016 campaign.

Not everyone on the right bought into birtherism. Some, such as talk show host Michael Medved, slammed the conspiracy theory. "Birtherism, he said, "makes us look weird. It makes us look crazy. It makes us look demented. It makes us look sick, troubled and not suitable for civilized company."

But many leading Republicans either stayed silent or refused to denounce such an outrageous lie. One reason for their reluctance: A Public Policy Poll in February 2011 found that birthers had become a majority among likely Republican primary voters—51 percent said they did not think Barack Obama was born in the United States. Birtherism was not a fringe idea in the GOP. The poll also suggested, as Steve Benen noted in Washington Monthly, that "candidates hoping to run sane campaigns will be at a disadvantage in the coming months." Republican voters who doubted Obama's legitimacy tended to gravitate to candidates like Palin, Newt Gingrich and Mike Huckabee (all of whom would play key roles in Trump's 2016 campaign).

In private, conservatives who knew better justified their return to the dark fringes on the grounds that it fired up the base and antagonized liberals. Or as Palin put it so memorably in 2016, "It's fun to see the splodey heads keep sploding." The result was a compulsion to defend anyone attacked by the left, no matter how reckless, extreme or bizarre. If liberals hated something, the argument went, then it must be wonderful and worthy of aggressive defense. So conservatives embraced the likes of Christine O'Donnell, a failed Senate candidate who ran a curious ad denying rumors she was secretly a witch. They defended Todd Akin, a former Missouri congressman who said female victims of "legitimate rape" rarely get pregnant. We treated these extremists and crackpots like your obnoxious uncle at Thanksgiving: We ignored them, feeling we could contain them or at least control their lunacy.

We were naive. By failing to push back against the racist birther-conspiracy theory—among other harmful, batty ideas—conservatives failed a moral and intellectual test with significant implications for the future.

We failed it badly.

Safe Spaces and Angry White Men

There is, of course, another side to the story of how the right lost its mind.

Decades of liberal contempt, including the almost reflexive dismissal of conservatives as ignorant racists, had created deep antipathy on the right. And during the Obama years in particular, many conservatives felt attacked. First there was the massive stimulus package, which threatened to balloon the national debt. Then the Democratic Congress rammed through Obamacare with the barest of partisan majorities. These moves came at a time when conservatives felt their free speech and religious liberty were under assault, when the Internal Revenue Service was targeting Tea Party groups, and on university campuses activists began enforcing their demands for ideological conformity, complete with lists of microaggressions, trigger warnings and safe spaces. Later, Democrats began dismantling the filibuster, while Obama, frustrated by gridlock in Congress, started issuing a dizzying array of executive orders on issues ranging from immigration to clean power.

The right distorted and exaggerated all of these issues. But Democrats seemed to act as if their success were preordained, not merely by history but by demographics, assuring themselves that as America became younger and more diverse, it would deliver one liberal win after another. Not content with winning historic victories on gay marriage, some progressives called their opponents bigots, deriding their religious faith as hatred and discrimination. The goal was not tolerance but to drive out dissent. Or so it seemed to many conservatives, especially evangelicals, who came to feel they were not simply losing the culture war; they were being dismissed by a country they no longer recognized.

During the 2016 campaign, for instance, commentators on the left expressed legitimate concern that Trump was encouraging violence at some of his rallies. At the same time, conservatives were inundated with stories, links and video clips of protesters chanting "What do we want? Dead cops! When do we want it? Now!" and "Pigs in a blanket, fry 'em like bacon." But on cable television, they watched their concerns about law and order denounced as racial "dog whistles."

As the Democrats became a party dominated by a highly educated, urban elite, its traditional blue-collar base felt increasingly disenfranchised. Many called them "angry white men" without really asking if they had legitimate reasons to be angry. The left, for instance, embraced the notion of "white privilege," even as white working-class America entered a period of acute decline, as blue-collar workers faced devastating job losses and a mounting opioid crisis.

The alienation of center-right voters was especially unfortunate because the excesses on the left pushed many small-government conservatives into an unnatural alliance with the authoritarian and nationalistic right.

Cementing that alliance: the newly emboldened right-wing media—a place where facts became malleable and loyalty mattered far more than truth.

The Fake News Revolution

Since the 1950s, conservatives have criticized the bias and double standards of the mainstream media. And much of the criticism has been deserved. Conservatives may exaggerate media bias, but they do not imagine it. The double standards made for daily fodder on my radio show for the past 23 years.

During much of that time, I was proud to be part of the conservative media. I frequently shared the latest column by Charles Krauthammer or set up topics by reading a Wall Street Journal editorial on the air. Other hosts provided a broad forum for conservatives to share their views. Sure, we had our problems, our excesses—particularly during the Bill Clinton years. But I genuinely believed we were helping people become savvier, more sophisticated analysts of current affairs.

During the Obama era, however, we crossed a line. The right's echo chamber didn't just remain silent about the crackpots in our ranks, it embraced them, exploiting their insanity for clicks and ratings. Take Matt Drudge. His site, the Drudge Report, consistently ranks as one of the top five media publishers in the country, often drawing more than a billion page views a month. Media critic John Ziegler describes him as the tacit "assignment editor" for conservative talk radio, right-leaning websites and a significant portion of Fox News.

But at some point in the past decade, Drudge began linking to Infowars, a website run by Alex Jones, a conspiracy theorist extraordinaire. On his site, Jones has suggested that the U.S. government was behind the September 11 attacks, the Oklahoma City bombing and the Boston Marathon explosions. He would be hilarious if people didn't take him so seriously. And in linking to his stories, Drudge broke down the wall separating the full-blown cranks from the mainstream conservative media, injecting a toxic worldview into the right's bloodstream.

Evidence of that toxicity came on the campaign trail on May 3, 2016. Months before the GOP convention, as Trump was competing against Ted Cruz for his party's nomination, the birther in chief used yet another conspiracy theory to his advantage. This one was about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the bogus theory that Cruz's father was involved in it. "His father was with Lee Harvey Oswald prior to Oswald's being—you know, shot," Trump said, citing a story in the National Enquirer, a fake news tabloid owned by his ally David Pecker. "That was reported, and nobody talks about it.… It's horrible."

Trump not only got away with this gambit; he doubled down, embracing Jones by appearing on his show. The Donald also enlisted the help of Breitbart bloviator Steve Bannon as his campaign strategist—a man who had turned his website into a platform for the hate-mongering "alt-right."

Never mind that these sites were pushing fake news and Pravda-style propaganda—that was the point. By then, conservative media—from Fox News to Rush Limbaugh—had convinced their audiences to ignore and discount anything that came from the mainstream press. The cumulative effect had destroyed much of the right's immunity to false information. The media's dramatic failure to get the election right made it easier for conservatives to ignore anything outside their bubble. So it should have come as no surprise when false stories—blasted out by Russian interests and others—became a major campaign issue. "The American Right," Matthew Sheffield wrote on the American Conservative website, "has become willfully disengaged from its fellow citizens thanks to a wonderful virtual-reality machine in which conservatives, both elite and grassroots, can believe anything they wish, no matter how at odds it is with reality."

The proliferation of hoaxes—and the number of gullible voters who believed them—should have inspired introspection among conservatives. It didn't. Those of us who were slow to join the bacchanal were denounced as sellouts, traitors or elitists. Under the withering fire of social media trolls, one GOP politician and commentator after another fell into line.

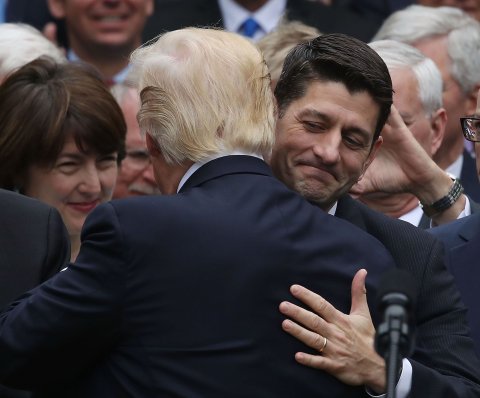

Those who didn't faced the wrath of their base. When Paul Ryan denounced Trump's statements about a Mexican-American judge presiding over a case about Trump University, he was hit with an avalanche of opprobrium from many of his fellow conservatives. They believed winning the election was more important than pushing back against racial animus. They were wrong.

By Trump's inauguration, the GOP had morphed from the party of the right to the party of the Donald. Conservatives who had previously agreed that Russia posed a global threat pivoted to embrace Putin as an exemplar of white Christian civilization; Tea Party activists who had railed against deficit spending accepted calls for a massive stimulus; the party of free markets endorsed protectionism and an economic policy that seemed driven by personal fear and favor; constitutionalists watched silently as the rule of law was undermined and norms of public integrity ignored. After Trump won the presidency, activists who had clamored to "burn it all down" suddenly pivoted to demand party loyalty and virtual lockstep support of policies, even when they conflicted with fundamental principles or contradicted what Trump had previously said.

A movement once driven by ideas during the Reagan era—back before the advent of Rush Limbaugh or Fox News—now found itself dominated by Kardashian-like hosts, intellectually dishonest shills, cynical careerists and alt-right bullies. Recent debates among conservatives, one commentator on Twitter quipped, "show[ed] the nuanced differences between a YouTube comments section and a chain email to your grandfather." This has paralleled a surge in the anti-intellectualism in American life, perhaps aided by compromises among the people whose judgment and ideas I once relied upon and trusted.

Thomas Aquinas warned of the dangers of the "man of one book." This now seems quaint. We live in an age where political leaders such as Trump no longer read books at all. They just watch television and tweet, rallying supporters with outrage and misspellings.

This is the covfefe we created.

Confessions of a Recovering Liberal

In the 1970s, I was a liberal, until I looked around and decided I no longer wanted a part of what that had come to mean. I hated the left's smugness, its stridency and dogma. I also felt many of the well-intentioned social programs seemed to hurt the very people they were designed to help. My decision came slowly, but it was liberating to break free from the cant of tribal politics and its tendentious talking points.

My circumstance today feels familiar. If the conservative movement is defined by the nativist, authoritarian, post-truth culture of Trump and Bannon, I want no part of it. So once again, I am an ideological orphan.

Despite the demands that conservatives obey the new regime, precisely the opposite is needed. Rather than conformity, conservatism needs dissidents, contrarians. It needs people who believe in things like liberty, free markets, limited government and personal responsibility—but who have no obligation to defend the indefensible or rely on alternative facts. It needs people who can affirm that Trump won the election fairly and freely but recognize the gravity of Russia's interference in the campaign. It needs those can support tougher border controls and still be appalled by the cruelty and incompetence of the president's immigration bans. It needs those who applaud Trump's support for Israel but are still thoroughly appalled by his slavish adulation of Putin and his flirtation with France's Marine Le Pen.

This position will be a lonely one; we may lose some friends. But conservatives have a long history of being out of step with the spirit of the age. It's worth remembering that conservative spokesmen like Buckley were actively opposed to Nixon during Watergate, well before he stepped down. Today, there are no "Nixon conservatives," short of maybe Roger Stone.

They are extinct. And good riddance.