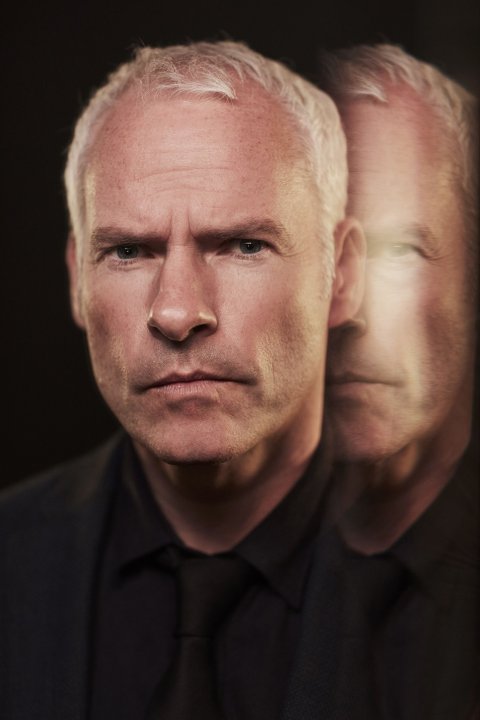

In 1994, a 24-year-old unemployed Londoner named Martin McDonagh sat down and wrote seven plays in just a year. Six were set in the stark terrain of Connemara and its nearby islands, the rural area of western Ireland where his parents were born. The seventh play takes place in a future dictatorship, where secret police interrogate a playwright after a mad man begins committing the gruesome acts of child torture described in his work.

That last one, The Pillowman, is named for McDonagh's idea of a fairy-tale character—a man made of pillows who mercifully convinces the tortured children to take their own lives. The Irish plays are populated with similarly cheery sorts, among them a sadistic soldier who unleashes murderous hell after he finds his beloved cat dead (The Lieutenant of Inishmore ); a boy with creeping tuberculosis who vainly dreams of movie stardom—when he's not being beaten half to death by the locals (The Cripple of Inishmaan); and a lonely woman who kills her spiteful, belittling mother with a fire poker (The Beauty Queen of Leenane).

Most of these plays are, improbably, comedies. McDonagh, you see, has a rare talent for wringing belly laughs from unrelenting misery.

Three years after writing those seven plays, four were simultaneously running on London stages—a feat supposedly matched only by Shakespeare—and many would eventually move to Broadway, winning a bushel of awards along the way.

In the late '90s, in a lull between transatlantic productions and drunkenly swearing at Sean Connery at an awards ceremony (well documented in the British tabloids), McDonagh found himself on a school bus with a crew of activists driving from the American South to Nicaragua, picking up food and medicine from Christian churches along the way. "It was very left-wing," says McDonagh, who describes his participation as "just going along to carry stuff."

Outside of a town in Missouri, whose name McDonagh can't remember, the bus drove by a set of billboards that accused local police of failing to capture a killer. "The billboards stayed in my mind forever, really," says McDonagh. "Who would feel that much pain and anger to take such a step?"

His new film, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, serves as an answer. Frances McDormand stars as Mildred, the working mother of a teenage daughter who was brutally raped, murdered and set on fire. She accuses the police chief (played by Woody Harrelson) and his cops of being derelict in their duties. "Once I decided that it was a woman, and a mother," says McDonagh, "the character of Mildred just popped out."

This isn't McDonagh's first film. In 2008 and 2012, he wrote and directed the cult caper comedies In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths. The latter stars, among others, Sam Rockwell, who also appears in Three Billboards. He's an old McDonagh hand at this point; in 2010, he starred alongside Christopher Walken in the playwright's A Behanding in Spokane on Broadway. In this latest collaboration, Rockwell plays a racist cop, locally famous for torturing a black prisoner.

McDonagh wrote the character for Rockwell, and Mildred for McDormand. "I knew it had to be Frances," says McDonagh. "I could never think of anyone else who'd be as good, and luckily, it never came to that." The actress, in her work with filmmakers Ethan and Joel Coen (McDormand is married to Joel), has proved a deft hand at gallows humor. Mildred's decision to buy the titular billboards sets off a Rube Goldberg machine of violence, retaliation and regret—with McDonagh's usual helpings of black comedy.

Three Billboards is a return to the female-centered complexity of some of those early Irish plays, and the film is the stronger for it. That Mildred has a son, an ex-husband, a job and a potential love interest—in other words, a real life—heightens the tension and deepens the emotion. "As a young man, I used to write good parts for women, and I wanted to get back to that," says McDonagh. "Not just in a simple kind of feminist way, although that was part of it. Writing someone as strong as Mildred takes the story to so many surprising places."

The town of Ebbing, Missouri, is fictional. "It had to be set in one of the Southern states, but, to be honest, I liked the three syllables of 'Missouri' and the flow of the line," says McDonagh, who has never been overly concerned with questions of authenticity. Nevertheless, he generally nails local vernacular and affect. His most recent play, Hangmen, is about England's last executioners in the northern English town of Oldham. The director of the play's critically acclaimed West End run happened to grow up in Oldham, and he praised McDonagh for the script's verisimilitude—accomplished without one visit to a town just a few hours from the writer's home in London.

With Three Billboards, McDonagh stumbled into some luck. "I didn't know what the Missouri accent was when I began writing," he says, "and once I checked around, I found there are four or six Missouri accents. You can get away with murder, literally."

Rockwell, on the other hand, did his due diligence, capturing local lingo by riding along with cops in Springfield. For all that work, he can remember only one word in the script that got Missouriized: "Instead of saying 'county jail,' we said 'clank.'"

One character manages to work "betwixt" into a sentence—random enough to seem like a local predilection. But McDonagh says it was cribbed from a favorite film, the classic 1955 noir thriller The Night of the Hunter, starring Robert Mitchum. "I can't tell you whether or not anyone has ever said that in Missouri."

The film's unflinching references to institutional racism and police brutality, however, ring painfully true to American viewers. "I hope we paint as evenhanded a picture as is possible," says McDonagh, "but it would have been very wishy-washy of me to back down from how I see certain aspects of police relations in the U.S."

McDonagh finished the script eight years ago, before Ferguson, Missouri, became synonymous with police racism. "I did wonder whether the film should still be set in the state, since it might look like a specific reference," he says. "But I thought, you know, fuck it. At this point, there aren't many places you can set it and avoid that."

The American characters in Seven Psychopaths also expressed a pointed dislike of the police. Does he see American cops as worse than those in his country? "I think it's a transatlantic dislike for cops," says McDonagh with a laugh. "Hitchcock always had a profound hatred for the police, funnily enough."

Rockwell made friends with the cops he rode along with, and he gave them a chance to read the script. "They really liked it," he says. "They know racism exists, but the cops I met were really, really good guys."

For McDonagh, the film is, first and foremost, about Mildred. "My allegiances were always with her," he says. "I guess a lot of my work is about the outsider—anarchism might be too strong a word for some of these people, but a distrust of police has always been a part of anarchism."

"You know, I've never gotten into any trouble with [cops]," McDonagh adds. "But, then, I'm not a young black man in the Southern states of America, or anywhere else."

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is out November 10.