James Mattis has spent the past few months traveling the globe with Grant, Ron Chernow's biography of Ulysses S. Grant. His heavily dog-eared copy details the mutual respect and affection shared between Grant, the top U.S. military leader during the Civil War, and his boss, President Abraham Lincoln.

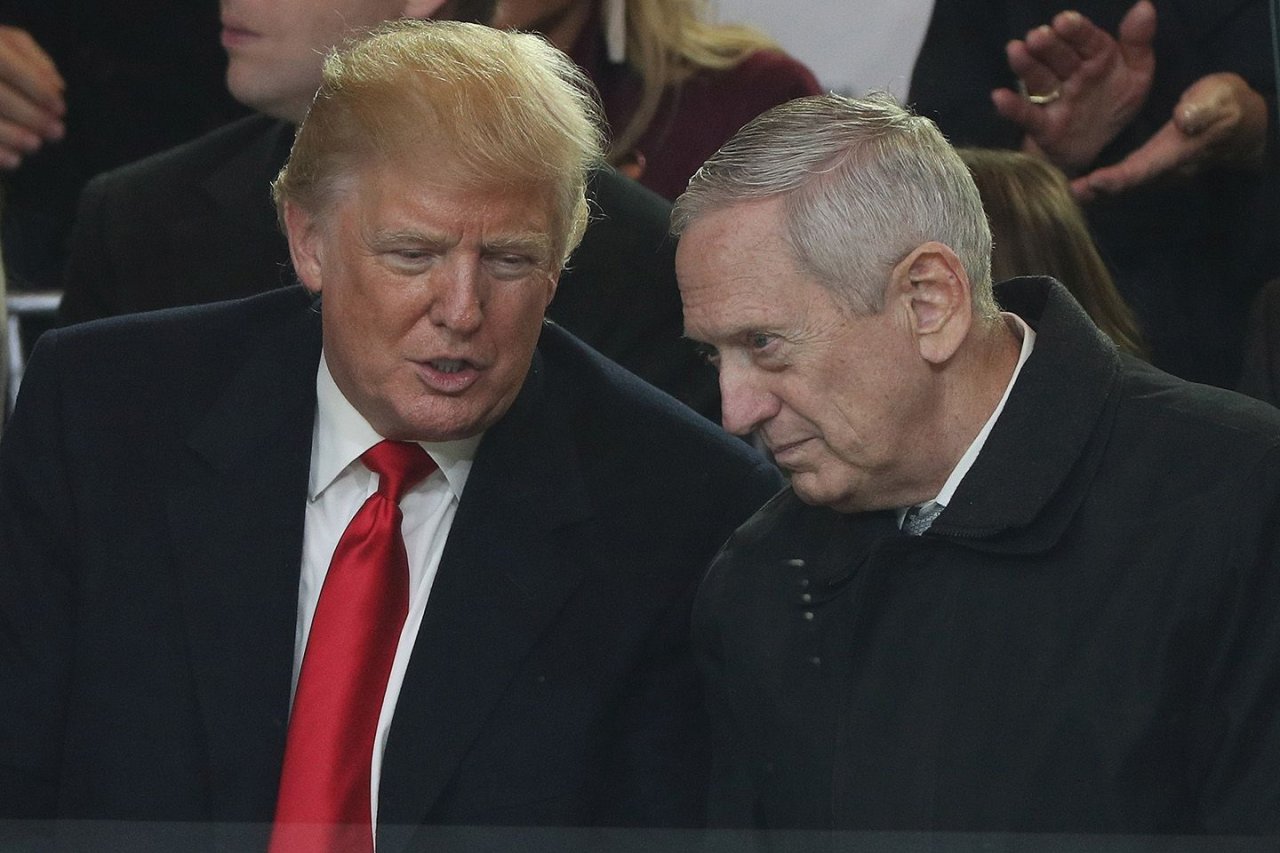

While Grant publicly supported Lincoln, Mattis, the secretary of defense, has been noticeably quiet about his president, Donald Trump. At a bizarre Cabinet meeting in June 2017, in which nearly every other official offered effusive praise for Trump, Mattis didn't.

Instead, he's been traveling the world while trying to hold back a rush to war on the Korean Peninsula, born of a rhetorical spat between his boss and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. His plane is a Cold War–era Boeing E4-B designed to help run a nuclear war from the air, a prospect he's hoping to avoid.

Mattis is facing a surge of support from within the White House for a pre-emptive war against Pyongyang. He's also considering deploying more cyberweapons to slow Kim's nuclear program, while pushing more aggressively for any kind of diplomatic solution. A war could cost up to 3 million lives. It is a conflict Mattis seems eager to avoid—and there's a weariness about him that's evident in the bags under his eyes.

Over the past year, the retired Marine Corps general has served as a reassuring presence for allies put off by Trump's talk of isolationism, Moscow's aggressive moves in Ukraine and Crimea and Beijing's penchant for building runways and bases on every available strip of land in the South China Sea.

While Trump and Kim trade insults and threats, Mattis talks about North Korea in calculating terms, always insisting that the tit-for-tat barbs are outside of his purview. When Trump threatened "fire and fury" against North Korea in August, Mattis said that "the rhetoric is up to the president." He refrains from responding to Pyongyang's direct threats and won't handicap the odds of conflict. "I have modest expectations of my ability to predict Kim Jong Un's behavior," Mattis tells Newsweek.

He cuts off questions about potential war plans, pushing the need for diplomacy. "They [war plans] exist so that the diplomats speak from a position of authority that they have to be listened to," he says. "Because an attack on the Republic of Korea will be severely rebuffed if it's attempted."

Mattis is also careful to avoid the appearance that he and Trump may disagree. It's perhaps why he's one of the only senior figures on the president's national security staff who hasn't had a major public dustup with his boss—and thus plays an outsized role in shaping U.S. foreign policy. "As crazy as Trump may be," says former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, "deep down he has trust in Mattis's judgment, and in a very significant way that relationship may be what's saving us right now from doing something stupid."

This year, the Trump administration tried to cut funding for the State Department by 30 percent. It simultaneously sought to increase Pentagon spending, a sign of how it values military action versus diplomacy.

And to an extent, Mattis has been forced to fill both roles, often meeting with foreign ministers and heads of state to represent American interests. He tries to appear perfectly in sync with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, noting that the two frequently coordinate their moves, despite the lingering rumors that the man supposed to be America's top diplomat may soon be leaving Trump's Cabinet. The two have reportedly teamed up on many contentious issues within the White House, from maintaining the Iran deal to pushing back against calls for a pre-emptive strike against North Korea.

Nearly every meeting Mattis takes includes discussion of how to manage Kim. North Korea isn't the first American enemy to acquire nuclear weapons over U.S. objections. Nor is it the only nuclear power that worries Washington. Pakistan's intelligence service has ties to so-called terrorist groups, and the country has poorly secured nuclear weapons stockpiles. But unlike North Korea, Pakistan talks with the U.S. "We've always had some relationship with Pakistan," Chuck Hagel, one of Mattis's predecessors, tells Newsweek. "It's been essentially transactional, but we've had a pretty stable relationship with Pakistan. You can go through the other nuclear powers as well."

What makes the current situation different to Mattis is that North Korea and South Korea, and by extension, the U.S., are still at war and have been since the 1950s. "There's been no peace treaty, there's only an armistice," Mattis says.

Kim's state is also largely closed off from the outside world. There no diplomatic relationship with the U.S., and American intelligence on Pyongyang's nuclear program—and the country's intentions—remains spotty.

The lack of intel is part of what is driving talks of a pre-emptive strike against North Korea—a risky move that experts say could cause all-out war. The idea behind such a limited campaign is that it would demonstrate the U.S. is serious, without threatening Kim's power. But no one knows how the North Korean leader would respond. Even if he eschewed nukes and a more conventional war broke out, the civilian casualties would be enormous.

"A limited attack tries to ignore the fundamental principle that the consequences of that kind of attack are totally unpredictable," says Panetta, who ran the CIA before he took the top job at the Pentagon. "[It] could result in not only the loss of millions of lives but the possibility of a nuclear confrontation."

Mattis is aware of this conundrum, having compared potential casualties in a conflict to those of the last Korean War, which claimed millions of lives. But his job requires him to draw up a potential plan and brief the president about the consequences.

There are, of course, limits to what any secretary of defense can do. "The secretary of defense does not make policy," says Hagel. "That only comes from the president, the White House."

And that makes the relationship between Trump and Mattis critical. "You have a very inexperienced White House, quite frankly," says Hagel. "You've got a president who campaigned on a pretty simple platform in 2016—elect me president of the United States, I know nothing about the job."

Mattis, meanwhile, will have to adapt to the changing nature of warfare. He has four decades in the military, although most of that came before the advent of cyberweapons, which North Korea has used in recent years to sidestep direct conflict. The most infamous example: the attack on Sony after that company produced a movie mocking Kim. The U.S. has reportedly used cyberweapons to disrupt the development of North Korea's nuclear weapons, and that could be a strategy Mattis uses again in the near future. "We have a hell of a lot better chance of controlling escalation with cyber," says Panetta, "than we do with a bomb."

But if the defense secretary can't get Kim to give up his nuclear weapons, his only option, other than war, may be a return to the strategy the U.S. used for decades against the Soviet Union: containment and deterrence. Kim, according to Hagel and Panetta, is a rational leader, not a madman; he's someone who could be induced to change his behavior. And a war, they say, might be avoidable, if the U.S. can apply the right pressure on Pyongyang. If he agrees, Mattis may be forced to dust off those strategies as he leads the world's oldest nuclear power against the ambitions of the world's newest.

As if to demonstrate this point, his doomsday plane, the decades-old aircraft built during the height of the Cold War, broke down on January 26 after a meeting with South Korea's defense chief, Song Young-moo. Mattis was forced to ride home on a stripped-down military cargo plane with a modified airstream trailer strapped to its floor. Inside the trailer for the overnight flight back to Washington, he kept Chernow's book by his side.