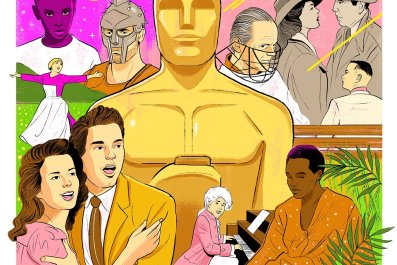

As the 2018 winter Olympics opened in Pyeongchang, South Korea, dozens of miles south of the heavily fortified border that has divided the Korean peninsula for more than half a century, 22 athletes from North joined the South Korean team under a blue and white "unification" flag. South Korean President Moon Jae-in shook hands with Kim Yo Jong, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un's younger sister, and Kim Yong Nam, the 90-year-old titular head of state in Pyongyang. Sitting awkwardly nearby was U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, who studiously avoided interacting with the North Korean guests.

And no wonder. The brief, polite spectacle between the Koreas masks an intensifying debate in Washington: What should America do as North Korea comes closer to being able to hit the U.S. with a nuclear warhead? The Trump administration's stated policy remains the same—that North Korea must stand down and get rid of the weapons it already has (a number that analysts say may now be as a high as two dozen.)

How, precisely, to achieve that result—or whether it is even achievable—are entirely different questions. One option is what's come to be known as the "bloody nose" strategy. It involves a "limited" strike against either a missile or nuclear site in the North and is intended to send an unmistakable message to Kim Jong Un: This administration will not acquiesce.

The strike's intention would not be to wipe out all of the North's nuclear sites, but rather persuade Pyongyang to rethink its strategy. The option is predicated on Kim's rationality; that once hit, he would not retaliate in a serious way because to do so would ensure the destruction of his regime, and the collapse of his country, in a war with the U.S. and its allies.

This option, the work of Trump's National Security Council under Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, was first raised as a possibility last year, and it has not gone away. The argument in favor of it is that living with a nuclear North is simply untenable from a U.S. security standpoint. It creates nightmarish proliferation concerns—everything from Japan and South Korea deciding to go nuclear themselves, to the sale of North Korean weapons of mass destruction to rogue regimes.

Related: What war with North Korea looks like

No one in the administration downplays the risks of a nuclear North—and they're all withering in their critique of the Obama administration's policy of "strategic neglect," which contributed to "this mess," says a White House official, who asked for anonymity because he wasn't authorized to speak on the record. But many Trump administration officials don't believe a limited, unprovoked strike makes any sense. Defense Secretary James Mattis and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joe Dunford, along with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson—all oppose the scenario. At a meeting of allied foreign ministers dealing with North Korea in mid January, Mattis emphasized "that this effort right now is firmly in the diplomatic realm. That is where we are working it."

The other foreign ministers needed to hear that, says a Japanese diplomat present at the meeting "because there seems to be a pretty consistent, serious undercurrent in this administration that war is an actual possibility, and that's spooking some people."

The jitters among allies spiked recently when the administration withdrew the nomination of Victor Cha, a former staffer on the NSC under George W. Bush. He had worked the North Korea issue for years, as ambassador to Seoul. Cha advocated a tougher policy toward Pyongyang than the one carried out during the Obama years, but he does not support the "bloody nose" strategy. Nervous outsiders saw the withdrawal of his nomination as a result of policy differences, but it turned out to be more complicated than that. One of Cha's family members apparently has business interests in South Korea that may have presented at least the appearance of a conflict of interest. "That was the 'red flag' that derailed him," said an administration source. Cha could not be reached for comment.

Yet to the consternation of many, the bloody nose strategy remains one the White House is considering. Critics are most alarmed by the assumption that "we know how Kim Jong Un would respond to a limited strike," says Sue Mi Terry, former North Korea analyst at the CIA and now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. "We don't necessarily know, and why would we test that?"

Within the administration, advocates for a tougher "contain and deter" strategy, as Terry calls it, are now putting together a series of options for the White House: they include a much more comprehensive package of sanctions, more aggressive interdiction of container ships carrying everything from amphetamines to missile parts that the North sells abroad for hard currency, as well as an aggressively ramped up system of missile defense in the United States, Japan and South Korea.

Yet this strategy may be ill-timed. Washington worries that the aftermath of the "unification" Olympics in South Korea will make Seoul reluctant for a tougher line against Pyongyang. At a lunch President Moon Jae-in, hosted on Saturday for the North Korean delegation, Kim Jong Un's sister, as expected, passed on invitation to the South Korean leader from her brother: come to Pyongyang after the Olympics and let's talk. The Trump administration was worried that Moon, who comes from the more dovish of the two main political parties in South Korea, would agree on the spot, given the feel good aftermath of the opening ceremony. For the moment Washington was relieved, because Moon handled the invitation deftly, saying he'd be happy to go when the "conditions are right." But that won't be the end of the matter, given that Moon will likely come under post Olympic domestic political pressure to make the trip.

Diplomacy, in other words, is hard enough when it comes to dealing with Pyongyang. But the nerve-wracking discussion about giving Kim a "bloody nose" makes Washington's task even more difficult.