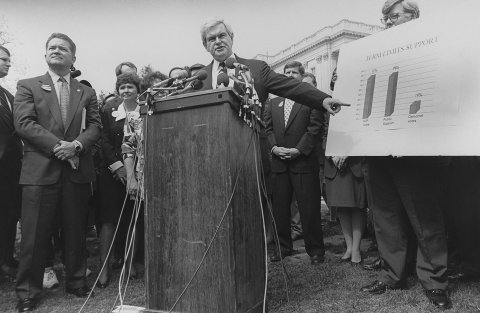

"The New Deal has been halted," The New York Times decreed on November 10, 1938, two days after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt suffered a crippling defeat in a midterm congressional election. "TAXPAYERS REVOLT," the accompanying headline said.

Roosevelt had campaigned vigorously for candidates who supported his progressive policies, which vastly expanded federal powers to lower unemployment and beat back the Great Depression. His message to voters: Obstructionists and "outspoken reactionaries" in Congress—in particular those from his own party—had to be expunged for the good of the Republic.

Voters' message to Roosevelt was no more ambiguous than his to them. "This is a democracy and it is healthy to have a strong opposition," a small-town minister from Indiana lectured the president in a letter. "No man is always right. You need criticism for your own good." Democrats lost 72 seats in the House of Representatives and seven in the Senate, and though they kept control of both chambers, anti–New Deal legislators were ascendant, their conservative factions invigorated by victory. Roosevelt would remain president for seven more years, but most of that period would be occupied by World War II. As the Times predicted, the era of freewheeling liberalism was over.

Presidents dread midterm elections, which come two years into their term. A sitting president can expect to lose, on average, 33 seats in the House and two in the Senate. Some have lost much more: Frustrated with the corrupt administration of Ulysses S. Grant, voters in 1874 handed 96 House seats to Democrats. Twenty years later, voters displeased with Grover Cleveland's handling of the Panic of 1893 rewarded Republicans with 116 House seats. The scope of that differential has not been surpassed since.

Barack Obama's first midterm, in 2010, was also a dark night for the Democratic soul. Although Democrats managed to keep the Senate, Republicans powered by the Tea Party movement won 63 House seats, in what Obama acknowledged was a "shellacking."

Some believe that an Obama- or even Grant-sized loss awaits President Donald Trump when he faces his own midterm test on November 6, 2018. His average approval rating for the first year in office, 38.4 percent, is the lowest in American history. Whether maligning the FBI for investigating his presidential campaign or threatening North Korea's Kim Jong Un on Twitter, defending a senior aide accused of hitting his wives or berating immigration from "shithole" countries, Trump has shattered every expectation of how a president should behave. Some people are thrilled, convinced that only a singular figure like Trump could rescue the moribund institutions of the federal government, in large part by breaking them. But judging by his popularity, or lack thereof, many more are mortified.

Democrats are accordingly preparing to make the midterm election such a devastating referendum that Trump's presidency never recovers. They believe they can not only win the House but even retake the Senate, where conditions are more challenging but not insurmountable. Were they to fully seize control of Capitol Hill, Democrats could perhaps fulfill a dream liberals have yearned to realize since the wintry morning of January 20, 2017: the impeachment of Trump and his subsequent removal from office.

"The left is going to show up," warned Senator Ted Cruz, Republican of Texas, in a recent speech. He is facing a resilient challenger in Beto O'Rourke, an energetic Democrat who has been raising more money than Cruz. "They will crawl over broken glass in November to vote."

Whether the GOP can win in '18 remains a matter of vigorous debate, as does the just-as-important question of what message Republicans hope to win on. Trump, however, doesn't seem especially worried about the glass-crawlers. "I have a feeling that we're going to do incredibly well in '18," Trump said during a recent rally in Cincinnati.

His supporters in the Republican Party's base aren't especially concerned, either. On February 21, the Conservative Political Action Conference, or CPAC, will convene outside Washington to celebrate Trump and his accomplishments. Conservatives know that Trump will fulfill their wishes only if bolstered by a compliant Congress. If even one of the chambers turns blue, the right's aspirations will be entirely nullified. The theme of this year's CPAC, "A Time for Action," suggests that conservatives realize the urgency of mounting a defense of their congressional majorities.

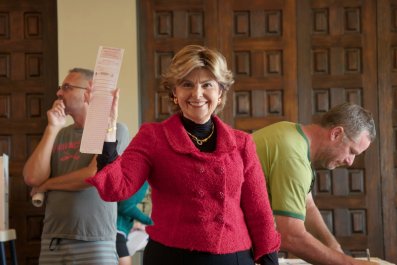

But no levee can stop a tsunami. Just a few miles north of CPAC's convention halls, in the political consultancies of Washington, D.C., establishment Republicans fear they're approaching an autumn of deep political discontent. Democrats are reportedly planning a coordinated assault on as many as 101 Republican-controlled seats in the House, where they need only 24 to take control. If Democrats are not yet organized, they are certainly energized, less by specific policies than by their general loathing of Trump. More than 400 women are likely running for congressional seats, in opposition to what they see as Trump's grotesquely midcentury machismo. Some may not run; others may not win. In aggregate, they represent a furious assault on Capitol Hill, the first mounted by Democrats against a Republican president since 2006.

"The 2018 midterm election is going to be a forest fire of such a magnitude for the Republican Party," says John Weaver, a veteran Republican consultant who worked on the presidential campaigns of Senator John McCain of Arizona. "My only hope is that through fire comes the rejuvenation of life."

'Great Republican Hair'

Trump adores the role of the outcast and underdog, a figure shunned by the elites but embraced by the people, a hurler of truths amidst the purveyors of platitudes. That was the pose he struck as a presidential candidate with few endorsements and legions of detractors. It was also a persona critical to his courtship of the Republican base, an effort that began with his appearance at CPAC in 2011.

The centerpiece of the convention is its straw poll, in which conservatives select their ideal presidential candidate. In 2010, their choice was Representative Ron Paul, Republican of Texas. The following year, Trump decided it was his duty to inform conservatives what a poor choice that was. The 75-year-old libertarian, Trump said in his first conference address, "just has zero chance of getting elected." While he didn't announce a run for the presidency, the erstwhile Democrat made a pitch remarkably similar to the one he'd issue from the lobby of Trump Tower four years later. "If I run, and if I win, this country will be respected again," he said, concluding his speech on a promissory note: "Our country will be great again."

Paul easily won the 2011 CPAC straw poll. Trump was a write-in candidate and earned piddling support. The Week deemed him one of the conference's "losers."

Like a persistent suitor determined to make his case, Trump kept returning to CPAC: in 2013 ("We have to take back our jobs from China"), 2014 ("With immigration, you better be smart, and you better be tough") and 2015 ("Our roads are crumbling; everything's crumbling"). He didn't go in 2016, canceling his appearance after reports of a planned walkout. Some cheered the news, which confirmed to them that Trump was, in the words of one attendee, not "a true conservative."

Last year, CPAC took place just a month after Trump's inauguration, with the president and his allies eager to tamp down reports of dysfunction and discord. Everyone was getting along in the White House, and the White House was getting along with Capitol Hill. The right was united, the left in wounded disarray. "President Trump brought together the party and the conservative movement," said chief of staff Reince Priebus. Sitting next to him was chief political strategist Steve Bannon, who agreed: "We understand that you can come together to win."

Bannon and Priebus were ousted last summer; neither is scheduled to speak at CPAC 2018, which begins on February 21. An estimated 10,000 conservatives will gather in National Harbor, Maryland. Some will come in MAGA hats, others in Brooks Brothers suits. Trump will be there, as will an appropriately eclectic array of luminaries, from British nationalist Nigel Farage to Fox News host Jeanine Pirro.

Overseeing the event will be Matt Schlapp, who became the head of the American Conservative Union in 2014. I met Schlapp in the organization's headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia. A cheerful 50-year-old, he resembles a suburban dad who likes to end his evenings with Fox News and a Bud Light. In fact, he is one of the most well-connected men in Washington. His wife, Mercedes, is a high-ranking communications official in the White House. And he prefers martinis.

Schlapp is not worried about Trump, and he is not worried about what Trump might do to Republican prospects in November. He evinces something approaching pity for those who think that "great Republican hair," as he puts it, is all it takes to sell a candidate to the party's conservative base. During the Republican presidential primary, some of Trump's 16 competitors weren't especially eager to make their way to National Harbor in 2015, Schlapp recalls. "Some of those campaigns were just sweating bullets at the idea of even stepping on that stage," he says. "If you say you're a conservative but are uncomfortable talking to conservatives, that's weird." Trump displayed no such hesitation. He couldn't afford to.

Yet neither Schlapp nor anyone else I spoke to could articulate what Trumpism was, let alone how Trumpism meshed with conservatism. "There is no such thing as 'Trumpism,'" the conservative writer Roger Kimball declared last year. Instead, there are things that Trump has done and conservatives have celebrated: giving lifetime federal bench appointments to conservative jurists; passing a $1.5 trillion tax cut; the systematic rollback of the federal regulatory infrastructure. All this, Schlapp says, has made the Republican base "ecstatic." So has, no doubt, what supporters see as the masterful trolling of liberals and the news media.

But the ecstasy of the base is the agony of the mainstream. Republicans closer to the political middle believe they have handed their party to someone who is only a conservative of convenience, one whom party leaders frequently have to scold—on the treatment of women, race relations, nuclear gamesmanship—as if he were a wayward understudy. Some even welcome a Democratic wave, should it remind the GOP what it stands for. "It's better for us to lose power for a generation than to continue this fraud," says Bruce Bartlett, an adviser to Ronald Reagan who has become a member of the Never Trump brigade.

Schlapp dismisses the Never Trumpers as false prophets of political doom who have intellectualized their own irrelevance. "They just have gotten everything wrong," he says. Trump's victory is "an indictment of everything they've done—and they don't like that. It's uncomfortable." For all the laments about Trump's lack of genuine conservative convictions, the GOP has indeed become the party of Trump. In January, a Pew Research Center found that 81 percent of "conservative Republicans" support a barrier along the border with Mexico; as of last spring, only 36 percent of Republicans stood for free trade.

Trump is an inimitable act, a set of flagrant contradictions that somehow hold together. Schlapp wants to reassure potential candidates that they don't have to go the full Trump. They probably shouldn't even try, lest they end up like Virginia gubernatorial candidate Ed Gillespie, a swamp creature supreme who was suddenly running ads about "dangerous illegal immigrants" and mourning the Lost Cause of the Confederacy.

"Take the parts you like," Schlapp counsels. For example, run on the tax cuts, but maybe not on the Access Hollywood tape.

Back when Trump's approval ratings were languishing in the 30s, there was little for Republicans to like, and even less to take. Now, the president has climbed back to the safer zone of the 40s. The generic ballot—which simply asks voters if they prefer Democrats or Republicans— saw a 13-point Democratic lead shrink in half (it has since risen to 6.9). Brian Walsh, a Republican consultant who runs a pro-Trump super PAC, says a generic battle that continued to favor Democrats by only 5 points would portend only a "bumpy night" for Republicans, whereas anything like a 12-point advantage on the generic would be "devastating." Because partisan redistricting conducted in 2011 heavily favored Republicans, explains veteran University of Virginia pollster Larry Sabato, "Democrats must win a clear majority of the popular vote by 5 to 6 percent nationally to have a good chance to take the House." (Pennsylvania has just redrawn its congressional district map to undo the effects of Republican gerrymandering; that will likely lead to Democratic gains in the House and, even more importantly, could signal a broader push away from district maps that favor the GOP.)

In 2016, Trump's chances of becoming president looked devastating too. But by beating Clinton, he seemed to prove that he could transcend history, demography, even destiny. And if he did it then, why can't he do it again?

It is this promise of victory that unites the right behind Trump. It may be what defines Trumpism, the nearly religious notion that he will somehow always elude defeat, especially when defeat seems certain, whether it is in the November midterms or a CPAC straw poll, which he has still never won.

An Artful Combover

Whit Ayres is one of the establishment Republicans that Schlapp believes are fated to "misunderestimate" Trump, to borrow George W. Bush's famous malapropism. A tall, courtly Southerner—on a business card, his name in full: Q. Whitfield Ayres—he carries himself with the bearing of a country judge. His consultancy, North Star Research, is based in a stately federalist row house in Alexandria. Hanging on a crowded foyer wall are photographs of some of the Republican senators on whose campaigns Ayres has worked: Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Marco Rubio of Florida, Bob Corker of Tennessee. Today, they happen to be among the GOP's loudest Trump dissenters on Capitol Hill.

Ayres did not think Trump was going to be president. On September 23, 2016, with Hillary Clinton ahead by 6 points in national polls and Trump seemingly engaged in protracted self-immolation, he voiced his frustrations on a CNN podcast. "We need to adapt to the new America, not by changing our principles," Ayres said, "but by applying those principles to a new kind of voter."

In 2013, the Republican Party published an "autopsy report" on the 2012 presidential election. The report warned that Mitt Romney's loss to Obama was the symptom of a deeper illness within the GOP. "Young voters are increasingly rolling their eyes at what the Party represents, and many minorities wrongly think that Republicans do not like them or want them in the country," the authors wrote. "We sound increasingly out of touch."

Five years later, the autopsy remains a divisive issue on the right—either a prophetic truth or the gloomy product of dispossessed malcontents. Trump's supporters say he has rendered the report irrelevant. "The autopsy talked about a lot of things," Schlapp argues, "but it never talked about the left-behind Americans." To him, Republicans have spent too much time running away from their own base, desperate to court constituencies that were never truly persuadable. The result was inevitable, embarrassing: Newt Gingrich cutting a television advertisement about global warming with Nancy Pelosi, Romney promising to open his "binders full of women." As far as Schlapp is concerned, Trump reminded Republicans who they really were. Having tired of great Republican hair, they found salvation in an artful combover.

When I told Ayres about Schlapp's argument, his lips wavered with something between dismay and disgust. "He's whistling past the graveyard," Ayres says. For him, data are destiny, and the destiny of a Republican Party that refuses to evolve is doom. In 1980, when Reagan first won, 87.6 percent of the electorate was white. By 2016, whites had fallen to 71 percent of the electorate. Millennials, meanwhile, now rival Baby Boomers in the voting rolls. Only 22 percent of these young voters are Republicans.

In a sunlit conference room, Ayres clicked through a PowerPoint presentation showing data from recent special elections and opinion polls. This had the distinct feel of an oncologist examining an inauspicious scan, unsure of how to frame the results with anything approaching optimism.

The most revealing slide was in a deck prepared by Republican analyst Adrian Gray. It looks like an alligator's widening mouth. The upper "jaw" is an orange line that shows how people felt about the economy. The line rises, indicating people believe the economy is in excellent shape. There is also some indication that the GOP tax cuts late last year are becoming more popular, or at least not quite as unpopular as cholera.

But there is another line, a dark green lower jaw, which sags. This is the president's approval rating, and the most troubling thing about it is how out of sync its gentle downward slope is with the growing economic optimism. Trump began his presidency with a 45 percent approval rating, according to Gallup. Only recently has it climbed back to that plateau, even as the nation approaches full employment, the economy grows at an impressive 2.6 percent pace, and the Dow Jones saw 72 record closes in 2017. (More recently, there has been a sharp downward correction to the stock market, though economists do not believe this portends a broader slowdown.) And while the president's approval rating has sometimes risen, it has not done so in a consistent manner.

"Virtually every president's job approval has been driven by the state of the economy," Ayres points out, but Trump "has severed the traditional link between presidential job approval and economic well-being." That lends some credence to the president's argument that he doesn't get sufficient credit for the economy, though he may be the one who prevents that credit from being tendered. Trump "keeps distracting people from all the good news with his various tweets and conflicts and battles," Ayres says. "President Trump's job approval is being driven by his conduct and behavior in office."

Economic renewal was the greater part of Trump's appeal. Those who voted for him have repeatedly indicated that they don't care about his behavior toward women, his troubling abrogation of norms, the ethical lapses of his Cabinet members. Now, however, they appear to have taken the economy largely for granted. "We really are about to learn if 'It's the economy, stupid' is still a rule or just a guideline," says Rick Wilson, one of the Republican establishment's louder Trump critics.

Ayres believes he knows the answer, and it isn't the one the White House wants to hear. He points to the numbers behind Democratic Lieutenant Governor Ralph Northam's defeat of Gillespie, the Republican candidate, in the 2017 Virginia governor's race. That election was decided in the suburbs of northern Virginia, whose upper-middle-class residents have stood to gain significantly from Trump's economic approach. Unlike the laid-off steelworkers in Pennsylvania, they benefit when the Dow climbs. If they work for a transnational corporation, they could see profit from Trump's deregulatory push, as well as from his tax reform package.

Yet the state of the economy proved immaterial on election night. In Fairfax County, outside of Washington, D.C., 255,200 Democrats cast their ballot for Northam, nearly doubling their turnout from the 2009 Virginia governor's race, which Republican Bob McDonnell won. In Loudoun County, Democratic tallies nearly tripled from the 2009 number to 69,788 in 2017. For many of these voters, a ballot for Northam was a ballot against Trump. According to exit polls, 34 percent of Virginians voted explicitly in opposition to Trump, not because they cared especially about the gubernatorial contest. Nearly the entirety of this resistance vote (97 percent) went to Northam.

Bannon likes to say that a nation is more than an economy. Voters who oppose Trump are coming to the same conclusion. Their retirement funds may be doing just fine, but their moral objections are too pressing to ignore. "I'm not convinced that voters are going to be so enamored of the economy that they are going overlook and forgive everything else that has turned them off for the last two years," says Michael Steele, the former chairman of the Republican National Committee.

Steele believes that the conservative embrace of Trump amounts to an arranged marriage fated to end in a contentious divorce. Like many Republicans who came of age after Barry Goldwater's cataclysmic defeat in the 1964 presidential race, he is troubled by what he sees as the party's return to the intransigent extremism that marked the Arizona senator's appeal.

"Ronald Reagan," he laments, "couldn't win a Republican primary today."

Tangled Up in Blue

Conservatives are still trying to figure out Trump. Liberals did so many months ago. For the Democratic base, Trump is a cancer to be excised from the American body politic. Anger at the president has united various progressive factions like single-payer medical insurance or a $15-per-hour minimum wage never could. This does not augur well for Republicans. "Voters who are angry tend to vote in midterms," observes Stuart Rothenberg of the electoral analysis newsletter Inside Elections.

Websites devoted to counting down the time to the 2020 presidential election have become surprisingly popular (as of this writing: 992 days, 9 hours, 10 minutes and 29 seconds). Until then, the easiest way for Democrats to punish Trump will be at the 2018 midterms, which take place in 264 days, 21 hours, 9 minutes and 13 seconds.

This anger should trouble Republicans. "There's almost nothing you can do to stop a wave," says pollster Sabato. "It's just beyond your control."

Republicans intend to spend the next several months trying to slow, if not entirely halt, this predicted Democratic onslaught. Such efforts will only intensify as the spring primaries approach. In January, the conservative billionaires Charles and David Koch invited top donors to their political groups, Americans for Prosperity and Freedom Partners, to Indian Wells, California, for a summit at which the midterms were a primary topic of discussion. The Kochs plan to spend as much $400 million on the midterms, $20 million of it to make the case for the tax plan Trump passed last year.

Despite that investment, fears of a rout persist. One evening at the Indian Wells conclave, Gail Werner-Robertson, a conservative activist from Nebraska, urged fellow conservatives not to cede November to Democrats. "This midterm is going to be hard," Werner-Robertson said, addressing Charles Koch directly. "We need everybody to help. We can't lose the progress that you all have fought so hard for. So I would tell everybody to get ready to fight. Get ready to double down."

As Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign so aptly reminded, wealthy donors can't turn lackluster candidate into gold. And the Republicans are very much facing a candidate problem. While the Democrats are eager to take the fight to Trump, many GOP incumbents are electing not to fight at all. Thirty-eight Republicans have decided to retire from the House. Several are doing so because they face allegations of sexual misconduct; others are prevented by term limits from keeping their committee chairmanships.

A good number, though, appear to have concluded that they simply aren't nimble enough to dance without tumbling between a furious Democratic electorate and an unpredictable president who could scuttle an election in rural Iowa with a single tweet. "They fear for their elections—or the job has just become so shitty," says former Reagan adviser Bartlett.

If a storm begins with rough surf, Democrats have reason to feel encouraged. Long derided for their lack of attention to down-ballot races, Democrats have now won 36 state legislature special elections since Trump's inauguration, many in districts that he won. Republicans have won only four.

Those results are one reason why Corey Lewandowski is concerned. Having served as Trump's first campaign manager until his firing in the summer of 2016, Lewandowski retains enormous influence with the president, despite having no official White House role. Temperamentally combative and restless, he exudes the urgency of someone who does not think there is much time left.

In late December, Lewandowski went to the White House for a meeting on political strategy. It ended with him shouting angrily on the South Portico. He does not regret the incident. "Look, my message to the president, his team, was that it has to be prepared for where things have the potential to go in November," Lewandowski tells me. A downward thrust of his index finger indicated things were going nowhere good.

"I'm just a realist, right?"

Lewandowski's target during the December brouhaha was Bill Stepien, the White House political director. "The White House is not currently structured to allow Bill to be successful," he says. "He doesn't have a 20-year relationship with the president, OK? He doesn't have enough clout."

With no small measure of nostalgia, Lewandowski referenced some of the best political minds in recent West Wing memory: Ed Rollins and, later, Ed Rogers for Reagan; Karl Rove for George W. Bush; David Axelrod and Rahm Emanuel for Obama. "These guys were killers, I mean absolute killers. And they were political animals, right? Circling each other, bitings each other's faces off every day.

"This is a very different White House."

(Officials I spoke to at the Republican National Committee and the National Republican Senate Committee disagree with Lewandowski's assessment. "Bill Stepien and I have spoken almost daily for at least the last 6 months," says Chris Hansen, the NRSC's executive director.)

In contrast to his fabled predecessors, Stepien does not look like he might bite off an ear, let alone an entire face. Young and cheerful, he retains a touch of brashness from his native New Jersey, but would otherwise make a fine foil for the darkly intense Lewandowski in a Hollywood buddy flick.

"There are reasons to be cautiously optimistic" in November, Stepien says. He and his team of 12 met with 116 candidates last year, in a process he compared to dating; they have begun to make endorsement recommendations to Trump.

"Candidates matter," he tells me over and over again, almost like a mantra.

The reference was obviously to Roy Moore, the former chief justice of Alabama who won the GOP primary in a 2017 special election for the Senate, only to lose in the general to Doug Jones. Many Republicans regard the race as aberrant because of Bannon's intense desire to unseat Republican incumbent Luther Strange. Since he has been excommunicated from Trump's counsel for his comments to Fire and Fury author Michael Wolff, there is widespread belief (and relief) that Bannon won't similarly meddle in the November races. But someone familiar with Bannon's thinking told me he plans a "big league" involvement in the midterms. Whatever that means, it is difficult to imagine the self-proclaimed streetfighter going gently into the November night.

Candidates matter, as Stepien says, and Republicans have struggled to recruit good ones in senatorial contests. Democrats will be defending 26 seats in that chamber, 10 of them in states carried by Trump. But a Republican offensive on the Senate has been surprisingly slow to build.

In Missouri, Republican frontrunner Josh Hawley is in trouble for blaming sex trafficking on "the terrible aftereffects" of the Sexual Revolution; he is also being outraised by resilient Democratic incumbent Claire McCaskill. In Ohio, state treasurer Josh Mandel abruptly ended his bid to unseat Senator Sherrod Brown, citing his wife's health. That leaves Republicans there without a top-tier candidate in that state. Nor do they have one in Montana to run again Jon Tester. Bannon had tried to recruit Erik Prince, founder of private security firm Blackwater. Prince said no. Nobody significant has said yes.

Republicans in Pennsylvania have settled on Representative Lou Barletta to challenge Bob Casey, the Democratic incumbent. Barletta had boarded the Trump train before many others, and Trump endorsed the Republican challenger earlier this month. But just days before that endorsement, a report had Barletta on seemingly friendly terms with Holocaust deniers.

Tennessee, which Trump won by 26, was supposed to be safe after Senator Bob Corker, a traditional Republican, announced his retirement last year. But now his anointed successor, Representative Marsha Blackburn — a conservative favored by Bannon — has fallen behind her Democratic competitor, former governor Phil Bredesen, by two points, according to one recent poll. That has led some Republicans to plead with Corker to reverse his decision and run for the Senate again.

Similar recruitment efforts persuaded Representative Kevin Cramer, Republican of North Dakota, to enter the race against Senator Heidi Heitkamp in that state. Republicans are also hoping that, in Missouri, Representative Ann Wagner decides to challenge McCaskill. This somewhat belated scrambling, writes Scott Wong of The Hill, "highlights an increasing nervousness among Republicans that their Senate majority — once seen as nearly invincible — may be at risk." And if the Senate goes blue, along with the House, the Trump presidency will find itself fatally besieged, either forced to make deals with Democrats or resign itself to two years of inaction.

Resisting the Resistance

Virtually everyone I spoke to agreed that there is one factor that could save Republicans in the midterm elections: Democrats.

"Democrats are always holistically bad at elections outside safe seats, and tend to latch onto issues that only their base loves," says Wilson, the Republican consultant with strong anti-Trump views. For many Democrats today, the main issue motivating them to vote is the possibility of impeaching Trump. California billionaire Tom Steyer has stoked that wish, ostensibly collecting money (and some 4.7 million email addresses) for an impeachment push, even as many members of Congress have urged him to quit what they see as his quixotic, self-serving campaign.

While some Democrats merely want to win, others want to vanquish Trump. "If you're a liberal with any interest in serving in Congress, you may never have a better chance than now," Alex Seitz-Wald of NBC News recently wrote. The resistance is energized, but that energy may be difficult for the Democratic establishment to harness. A surge of liberal candidates could make for expensive, contentious primaries that pull the Democratic Party to the left, making it more difficult to attract voters in moderate-leaning "swing" districts. Those are the very districts Democrats need to win.

Nor is it clear how anger at Trump will translate into an electoral strategy. Writing for the progressive blog Daily Kos, Democratic activist Nate Lerner recently warned that the party lacks a message around which candidates could unite. "While it may seem obvious to state that Democrats need a defining vision and message," he wrote, "all evidence thus far suggests one is not coming anytime soon. Too many key rising Democratic stars are focused on their own presidential aspirations, rather than the rebuilding of the party."

It doesn't help that Democrats will have trouble breaching what NPR's Mara Liasson calls "the mighty fortress of redistricting," the recent Pennsylvania decision notwithstanding. The 2010 midterms saw huge Republican gains in both state houses and governors' mansions. They used these to redraw congressional districts in ways that over-represented Republicans and under-represented Democrats. In a state thus gerrymandered, Democrats can win the overall popular vote but still lose House seats, simply because their votes count less.

It doesn't help that Democratic fundraising has been anemic. The Republican National Committee raised $132.5 million in 2017, versus the Democratic National Committee's $65.9 million. And the party is riven by conflicts between Obama centrists and Sanders progressives. "They have never recovered from their primary," Stepien says. "They have no party leader." DNC Chairman Thomas Perez has vowed a "50-state strategy" to retake legislative majorities across the nation. Some think the plan is "empty rhetoric," as one Democrat said to the Washington Examiner, because it is predicated on grants to states, not direct DNC involvement in races.

Stepien similarly thinks little of that effort. "I love that the Democrats are pursuing a 50-state strategy. I hope they do that," he says, adding that such a strategy would be inefficient. "There are some states that are not worthwhile investments for a political party to make."

A major test of Democratic strength will come next month, in the form of a special House election in Pennsylvania's 18th District, in the suburbs of Pittsburgh. The seat was vacated by Rep. Tim Murphy, who left Congress last year after news reports that the staunch anti-abortion crusader, who is married and has a child, had forced a woman with whom he was conducting a romantic relationship to terminate a pregnancy. The Democratic candidate is Conor Lamb, a 33-year-old Ivy Leaguer who served in the Marines. His opponent is Rick Saccone, who likes to say that he was "Trump before Trump was Trump." The 60-year-old supports Christian political causes and is against gun control.

"If the Republicans lose that seat," Lewandowski says, "I would be gravely concerned." About three weeks after we spoke, in mid February, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette deemed the race "far closer than expected," with a new poll showing Saccone up by only three points. Trump won PA-18 by 20.

'One-Man Rule'

As Roosevelt discovered, a president almost always loses in the midterms because voters want to remind him of their power to check his own. That is especially true when his party controls both chambers of Congress. "I am not willing, in the search for efficient management, to establish one-man rule in this country," Senator Edward Burke said ahead of the 1938 midterms. "If some waste and inefficiency are necessarily connected with a democratic form of government, we can well afford to pay the price."

At the Cincinnati rally earlier this month, Trump said he would not be "complacent" in his approach to the midterms. It is not clear what he meant, though it could have been a reference to his previously stated desire to campaign for candidates as many as five days a week.

His efforts might not help Republicans' chances. "Trump is going to be seen as a liability" in any district that isn't heavily Republican, says libertarian strategist Liz Mair. She points, for an example, to Southern California's suburban Orange County, a onetime bastion of conservatism that voted for Hillary Clinton. "I don't think I'd want the president there," Mair says. That makes for a cruel paradox for Republicans: Although the president is a skilled campaigner, he is unlikely to help in the swing districts where help might most be needed.

And there still remains the business of governing, however less glamorous it may be compared to the thrill of campaigning. Most candidates do not want the race to be about Trump because they can't imitate him. Sometimes, they can't explain him either. The president can help by giving them something else to campaign on.

The "policy" part of the equation in the White House today belongs to Marc Short, its director of legislative affairs. A veteran Republican operative on the Hill, he wants to corral Republicans behind Trump's message, so that they in turn have more than just last year's tax changes to run on.

The president's biggest priorities are immigration, the centerpiece of which is a border wall with Mexico for which Trump hopes to win $25 billion from Congress, and an infrastructure plan that could cost $1.5 trillion, with much of that cost absorbed by state and municipal governments. But Trump will need the support of Democrats in both cases. If he doesn't get it, he could face a second year without any significant legislative accomplishments.

Short acknowledges that Democrats are unlikely to help Trump, even on issues they nominally agree on, like infrastructure spending. "They are entrenched in their opposition to this president," he says. "They want to be more of a resist movement to stop anything that this president can do."

This was the posture of Republicans when they tried to make Obama a one-term president. They decided that no policy compromise was worth ceding a political victory. Democrats are now making the same calculation, waging that voters will reward combativeness more than compromise.

Meanwhile, each day brings a new poll and, with it, new suggestions about what the American people want and what politicians should expect. History is pretty clear about what we should expect. Then again, in politics as in all else, we want to believe ourselves superior to statistical trends. So we look for assurance in outliers, take comfort from the counterintuitive prognostications of pundits.

In the fall of 2009, exactly a year before Republicans stormed the House, Democrats lost gubernatorial special elections in New Jersey and Virginia. Some took these as the portent of a midterm rout. In The New York Times, Democratic strategist Ruy Teixeira assured that no such cataclysm was coming. "If any repudiation is going on, perhaps it is of the conservative wing of the Republican Party," he wrote, just as the Tea Party movement was gathering strength across the land.

And then there was the title of Teixeira's op-ed, perhaps its most memorable feature, so perfectly did it capture the hubris of a political movement that believes its ascent may yet go unchecked.

"Relax, Democrats," the headline said.