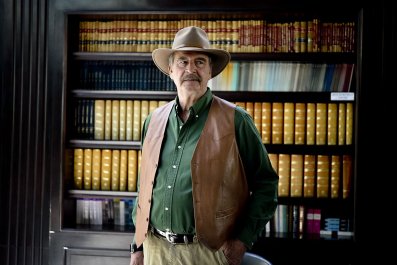

An overly tanned right-wing populist with a fervent base seemingly dodges scandal after scandal, until several women he's abused, insulted or exploited finally lead to his downfall. That scenario may sound like Donald Trump's presidency, albeit with a liberal fantasy ending. But I'm actually talking about Silvio Berlusconi, the flamboyant former Italian prime minister.

The two leaders have a lot in common. Both are wealthy demagogues with long records of bankruptcy and shady business dealings. Both are celebrities—Berlusconi once ran a TV empire, Trump had a hit reality-TV franchise. Both entered politics, claiming that only they could fix a broken political system—one from which they handsomely benefited. Both are savvy salesmen who appealed to disgruntled voters by projecting themselves—paradoxically—as cartoonish authoritarians and victimized everymen. Both became embroiled in sex scandals. Trump allegedly cheated on his pregnant wife with porn star Stormy Daniels (real name Stephanie Clifford), then tried to buy her silence just before the 2016 election. Berlusconi was accused of having sex with a young prostitute at a "bunga bunga" party. Both men also saw those controversies spiral into probes about cover-ups and the abuse of power.

Most Americans—like most Italians—don't really care about their leaders' sex lives. But they do care if their leaders are corrupt. They do care if they bribe people, using fixers who also sell their access to the head of state. So Trump—and his critics—may want to study Berlusconi's demise—and how he sullied the country's democracy on his way down.

The fall of the Italian media mogul began one night in October 2010 when Berlusconi—then in his 70s—allegedly gave a 17-year-old belly dancer named Karima El Mahroug 7,000 euros and some jewelry to have sex with him. The encounter may have remained secret, but months later, El Mahroug, known as "Ruby the Heart Stealer," was arrested on charges of stealing—not hearts but thousands of euros from her roommate.

Her first call from jail was to Berlusconi. Soon, the Italian prime minister pressured the head of police in Milan to release her, claiming that the girl—a Moroccan citizen—was the niece of Egypt's President Hosni Mubarak. Her arrest, he explained, could spark a diplomatic crisis.

Law enforcement leaked the story, and the ensuing media storm included lurid tales of orgies at Berlusconi's residence in Rome, where prostitutes were hired to dress like nuns and policewomen and role-play with the prime minister. Ever the demagogue, Berlusconi responded to the scandal by declaring, "It's better to be fond of beautiful girls than to be gay."

What also came out in the scandal: The libidinous leader used a proxy—businessman Gianpaolo Tarantini—to pay other women (prostitutes, porn stars and showgirls) to sleep with him and, later, to allegedly keep quiet about their randy romps and lie to the magistrates.

Ruby's story ought to have come as no surprise to the Italian public: A year earlier, Berlusconi's wife of 19 years, Veronica Lario, had filed for divorce, publicly accusing her husband of "consorting with minors." She wrote an open letter to Italy's main newspaper, La Republica, calling the prime minister "a sick man." Members of Berlusconi's political party and his media surrogates responded by leaking seductive photos of her and spreading rumors she was sleeping with her bodyguards, among other things.

Then there was Angela Merkel. Berlusconi never slept with her, but she certainly helped lead to his downfall. The German chancellor couldn't stand his naked corruption and misogyny. (It didn't help that he also referred to her as an "unfuckable bitch.") In normal times, the Merkel-Berlusconi beef would have been little more than a verbal spat. But it occurred in 2011, when Italy was in the throes of a financial crisis. The country needed a European Union bailout. The result: She demanded his ouster as part of the price for Italy's economic survival. And Berlusconi was forced from power and banned from public office for more than half a decade.

In 2013, he was sentenced to four years in prison on charges of financial fraud and tax evasion, though he ultimately had to do only community service. (He remains under investigation for witness tampering related to El Mahroug and others.)

Does Trump await a similar fate? It's unclear, but there are eerie parallels between his women troubles and those of his Italian counterpart. Take Stormy Daniels. Trump's personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, paid the adult film star $130,000 through a limited liability company just before the 2016 election to keep quiet about her alleged affair with the GOP candidate. He apparently considered it necessary so the story wouldn't leak and affect the New York real estate mogul's chances of winning.

But as was the case with Berlusconi, the scandal soon widened beyond just sex. Daniels's lawyer, Michael Avenatti, eventually revealed, among other things, how Cohen used his access to the president to make millions from corporations such as AT&T and Novartis and investment company Columbus Nova, which is tied to Russian billionaire Viktor Vekselberg—whom the U.S. recently sanctioned.

It's still unclear if the president knew what his lawyer was doing, but here again there is a Berlusconi parallel: As Tarantini helped find women for the Italian prime minister, he was allegedly courting wealthy businessmen, promising access in exchange for considerable sums of money.

So far, Trump's response to these scandals has also mirrored Berlusconi's. Both share a profound sense of victimhood. And both have fervently attacked the press and those who could potentially bring them down (in Trump's case, law enforcement; in Berlusconi's, the Italian judiciary).

The outcome of this strategy, at least for Berlusconi, was a partial victory. By the time the Italian prime minister was forced out, he had successfully discredited and delegitimized the courts, calling them a "cancer of democracy." (Only 39 percent of Italians still believe in an independent judiciary, according to Institute Eurispes, a European think tank.) Today, his toxic legacy lives on, and many among his base—about 25 percent of the country—still believe he is innocent. Which is why, after years away from public office, he may soon run again.