Updated | In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Paris beckoned African-American intellectuals hoping to escape the racism and conformity of American life. Chief among them: Richard Wright, the acclaimed author of Native Son and Black Boy, who arrived in 1947. He was soon joined by Chester Himes, an ex-convict who mastered hard-boiled detective fiction; James Baldwin, the precocious essayist; and Richard Gibson, an editor at the Agence France-Presse.

These men became friends, colleagues and, soon, bitter rivals. Their relationship appeared to unravel over France's war to keep its colony in Algeria. Gibson pressured Wright to publicly criticize the French government, angering the acclaimed author. Wright dramatized their falling-out in a roman à clef he called Island of Hallucination, which was never published, even after his death in 1960. In 2005, Gibson published a memoir in a scholarly journal recounting the political machinations his former friend had dramatized, telling The Guardian he had obtained a copy of the manuscript and had no objections to its publication. "I turn up as Bill Hart, the 'superspy,'" Gibson said of the story.

Wright's book now seems prescient. In a strange twist, on April 26, when the National Archives released thousands of documents pertaining to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, they included three fat CIA files on Gibson. According to these documents, he had served U.S. intelligence from 1965 until at least 1977. This was well after Wright wrote his book, and it's not clear if Gibson had engaged in espionage before that period. But his files revealed his CIA code name, QRPHONE-1; his salary (as much as $900 a month); and his various missions, as well as his attitude ("energetic") and performance ("a self-starter").

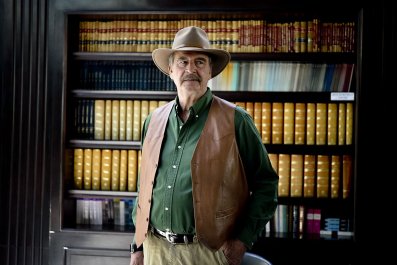

The most curious part of the story: Gibson is still alive. He's 87 and living abroad. (Gibson "will not be able to your questions," said a family friend who answered the phone at his residence.)

The CIA is usually vigilant about defending the confidentiality of its sources and methods. In announcing the release of the JFK files last year, President Donald Trump declared the records would be opened in their entirety, "except for the names and addresses of living persons." Save for Gibson's, apparently. (The CIA declined to comment for this story.)

Born in 1931, Gibson grew up in Philadelphia and attended Kenyon College in Ohio. A stint in the Army gave him a taste for European life, and he moved to Rome and then to Paris. He wrote a novel, a detective story called A Mirror for Magistrates, and fell in and out with Wright and other expatriate intellectuals.

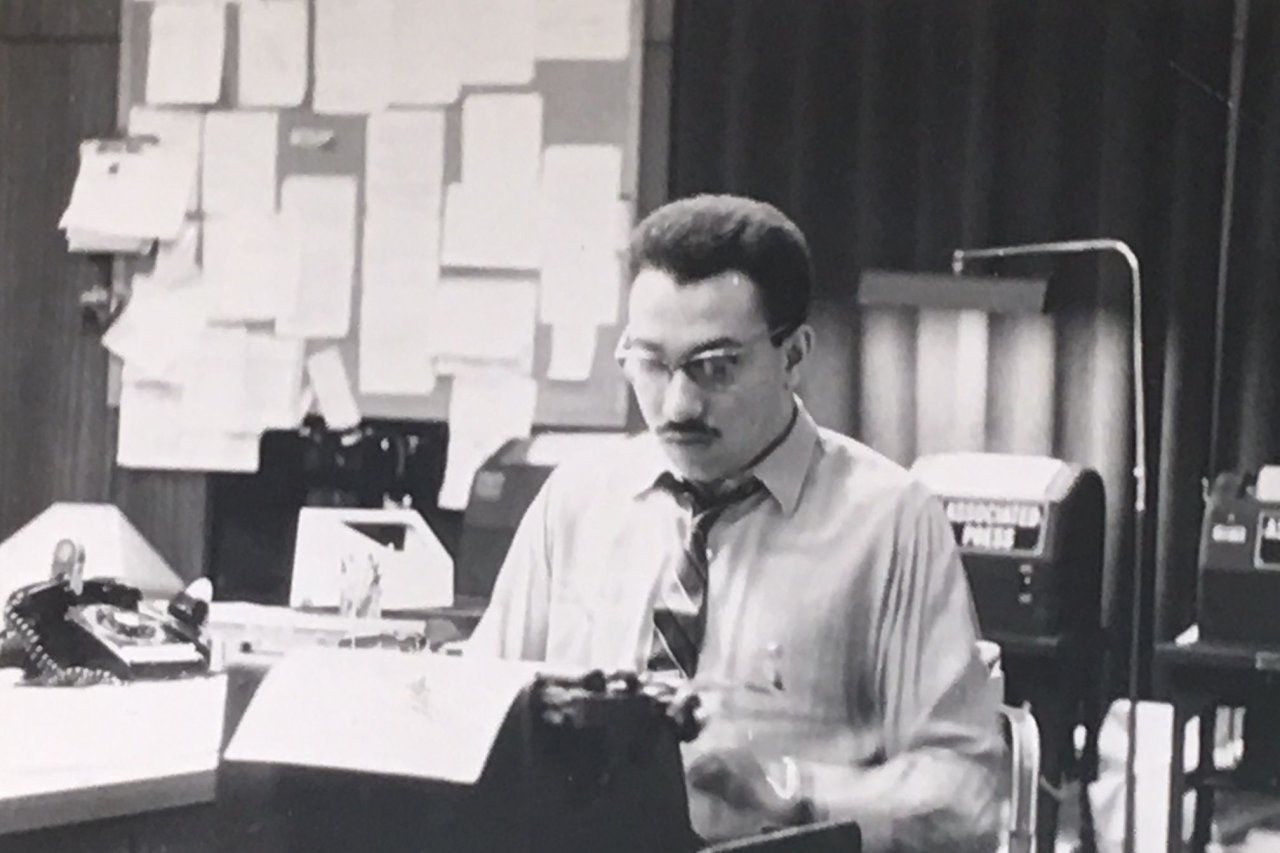

In 1957, Gibson left Paris and went to work for CBS Radio News, according to his newspaper reports. With a colleague, he covered the Cuban revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. In 1960, Gibson, who then sympathized with leftist movements, co-founded the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), which defended Castro's government from negative coverage in the North American press.

When he left CBS, Gibson took over running the FPCC, and it grew rapidly on college campuses. He resisted subpoenas from Senate investigators seeking to discredit the group and urged civil rights leaders to support the Cuban cause.

Yet in July 1962, Gibson quit the FPCC and wrote an anonymous letter on the group's stationery to the CIA. If the agency would arrange a secure meeting spot, he wrote, he could be of assistance.

The CIA figured out who wrote the letter and made contact with the young intellectual. He had moved on to Switzerland to become the English-language editor of a new magazine called La Révolution Africaine. In a January 1963 memo, CIA Deputy Director Richard Helms informed the FBI that Gibson had told an agency source about the ideological direction of the magazine—further left—and how it planned to relocate 15 staff members from Paris to Algiers.

When Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, the CIA asked Gibson about accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, who had corresponded with the FPCC. Gibson told them what little he knew and indicated he wanted to "maintain contact" with the U.S. government.

In the summer of 1964, Gibson had another falling-out, this time with the publisher of La Révolution Africaine, who accused him of being an agent of the FBI and CIA. Whenever the charge was repeated years later, Gibson shrugged it off. "If I'm CIA, where's my pension?" he told The Guardian in 2006.

By then, Gibson was no longer working for the agency. But his file shows that a Langley officer contacted him in January 1965 and arranged for a debriefing and "test assignment" that summer: "After recruitment and agreement to...[polygraph] examination, [s]ubject was introduced to his…case officer." He soon began working for the intelligence service as a spy.

Four years later, according to his file, the agency increased Gibson's tax-free salary of $600 a month to $900 a month (the equivalent of more than $6,000 in 2018 dollars). His mission: to report on "his extensive contacts among leftist, radical, and communist movements in Europe and Africa."

Gibson, his wife and their two kids settled in Belgium, where he lived the life of a cosmopolitan intellectual. He traveled widely and wrote a book about African liberation movements fighting white-minority rule. He also monitored the revolutionary poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who trusted him as an ideological comrade. In his letters to the CIA's spy, Baraka signed off with the valediction "In struggle." (Baraka's son, Ras, is the mayor of Newark, New Jersey.)

While the newly released CIA files don't include operational details, Gibson seems to have been a prolific spy. One CIA memo asserts that in 1977 his file contained more than 400 documents.

His quip to The Guardian notwithstanding, Gibson even had a CIA pension of sorts. In September 1969, his case officer noted that "QRPHONE/1 has begun to invest a portion of his monthly salary in a reputable mutual fund of his choice. This modest investment program will enhance financial security in the event of termination and/or a rainy day."

Gibson was still an "active agent" in 1977 when Congress reopened the JFK investigation and started asking questions about the agency's penetration of the FPCC in 1963. The House Select Committee on Assassinations asked to see Gibson's CIA file. The agency showed investigators only a small portion of it, but the entirety of the still-classified material became part of the CIA's archive of JFK records.

That designation would eventually change. In October 1992, Congress passed a law mandating the release of all JFK files within 25 years. Gibson's secret was safe for the time being. In 1985, he successfully sued a South African author who asserted he was a CIA agent. The book was withdrawn, and the publisher issued a statement declaring that "Mr. Gibson has never worked for the United States Central Intelligence Agency," a claim that no longer seems tenable.

In 2013, Gibson sold his collected papers to George Washington University in Washington, D.C. To celebrate the acquisition, the university held a daylong symposium, "Richard Gibson: Literary Contrarian & Cold Warrior," dedicated to "furthering our understanding of the intellectual and literary history of the Cold War."

With the release of Gibson's CIA files, scholars can now discern the hidden hand of the American clandestine service in writing that history. When it came to the character who inspired Bill Hart, "the superspy," Richard Wright's fiction was perhaps ahead of its time.

This story has been updated with additional context to reflect the version that appears in the June 1 print edition of Newsweek.