Christopher Plummer is talking about playing Iago, and I am becoming distracted by a monkey.

Forgive me: There is a magnificent painting in Plummer's living room, an 18th-century portrait of a mischievous monkey raiding a fruit platter, and it's on a wall just over his shoulder. The 88-year-old actor must be used to the distraction of his guests, because my wandering gaze produces a benevolent chuckle.

In fact, Plummer's house—a sprawling, century-old former barn hidden in the rolling woods of southwestern Connecticut—resembles a shrine to the animal kingdom, with monkeys, birds and other creatures painted on walls, embroidered on cushions and set within frames. Dogs, however, win: There's a painting of a pooch, and photos of Plummer's own now-deceased dogs. He's crazy for them. "I really like them better than people," Plummer confesses. "Also, I love to be loved. I need to be loved. And dogs can give you that in two seconds."

Humans might not give it up quite so fast, but there's plenty of adoration going around thanks to a late-career renaissance that makes Plummer's Sound of Music stardom seem like a distant prelude from another century (which it was, come to think of it).

Dogs, it turns out, are also abundant in his latest film, the dysfunctional-family comedy Boundaries, co-starring Vera Farmiga. She plays a struggling single mom who can't stop rescuing strays dogs off the streets; he is her pot-dealing father who was never around when she needed him. When dad is kicked out of his nursing home, the pair is forced to road-trip cross-country with her troubled son. This trigenerational plot is a bit reminiscent of Sidney Lumet's 1989 movie Family Business (in which Sean Connery plays the lawbreaking grandfather of Matthew Broderick), which is a neat coincidence since Plummer made his film debut in another Lumet movie, 1958's Stage Struck, and starred alongside Connery in the 1975 gem The Man Who Would Be King.

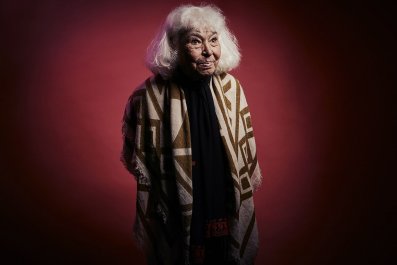

It seems no coincidence that Plummer often plays charismatic, quick-witted, larger-than-life (and devilishly handsome) characters: This is simply the energy he radiates. When he comes out of his house to greet me, he looks unfailingly dapper in gray slacks and a plaid blazer. The actor has lived here with his third wife, the British actress Elaine Taylor, since the early 1980s. (He has a daughter, the actress Amanda Plummer, from his first marriage to the late Tammy Grimes.) In his 2008 memoir, he says he moved to Connecticut when Hollywood became too lush, too tiresome: "Everything in life there seems to use the same plastic surgeon."

Plummer's character in Boundaries is based on writer-director Shana Feste's own father, a drug-dealing cardsharp. "He had a real taste for breaking the law," Feste says. "My college was paid for in envelopes of cash." When a casting director suggested Plummer for the part, she thought, No way: "Christopher is a master of Shakespeare and so refined, and my father was, you know, in and out of prison and covered in tattoos and smoked weed all my life."

But Plummer was intrigued by the screenplay—"I thought, I'd love to play this dreadful old man who never can find a bed to lie down on"—and brings an irresistibly naughty elegance to the part. "Some of the most talented actors in the world you can look away from on screen," says Feste, "and you can't look away from Christopher—even when he's doing absolutely nothing."

Plummer found inspiration in his own debauched past, back when he was a 1950s Broadway actor with a taste for booze and women. "There used to be a rule," he tells me, "that you weren't a man till you could go through a matinee of Hamlet pissed and hungover. Which we did!"

At the time, the Toronto-born actor was a master of the classics—Henry V, Hamlet, Cyrano de Bergerac, Macbeth—and his bar buddy was Jason Robards. "I understand you were a bit of a drinker," I say in polite understatement. "Everybody was in the early '50s," Plummer retorts. "Don't shake your gory locks at me! That whole group—God, they were never without a vodka. It was great fun."

Plummer is supposed to talk about Boundaries. Trouble is, he can barely remember it. "I've forgotten the plot," he says. "I've forgotten what the hell my character does." It was two years ago that he filmed it and a lot has happened since then.

In early November he received an unusual call: Ridley Scott needed a speedy replacement for a disgraced Kevin Spacey, who had played real-life billionaire J. Paul Getty in his already-shot historical thriller All the Money in the World. Scott flew in from London to convince Plummer, who had reportedly been his original choice for the part; the actor's talent for capturing historic figures is undisputed, and he was the right age for the role. But the studio pushed for a hotter name—a 57-year-old Spacey, who required layers of prosthetics to look old enough. Nevertheless, Plummer was wary; it seemed an impossible task given that the film was scheduled for released in December. "I thought, Jesus. This sounds…Christ. And then I thought, Wait a minute. This is kind of exciting."

Plummer has a way with unsavory men, and a theory about playing them. "I believe that when you get a sleazy character—like Iago, who was the arch evil of all the characters in literature—you've got to make him as charming as you possibly can," says the actor, who played Iago opposite James Earl Jones's Moor in the 1982 Broadway production of Othello, for which he received a Tony nomination (he's been nominated seven times and won twice). "Same with that unattractive creature Getty."

Long story short, Plummer was in front of the camera shortly after his talk with Scott, for just over a week of frantic, last-minute reshoots that cost $10 million and rescued the film from almost certain doom. All the Money in the World was released in time for Christmas, amid the media circus of Spacey's removal. "It saved the movie," Plummer says of Scott's decision to lose Spacey. "We would have had to shut down." In January, he learned he had received the highest accolades for his performance. "Nine days' work and I get an Oscar nomination! A Golden Globe [nomination]! I mean, what?"

So this was a surprise? "Oh Jesus, yes. I thought, Thank God I remembered my lines!"

Plummer had known Spacey over the years, but "Oooh"—an audible shudder—"I didn't know anything about that," he says, alluding cautiously to the allegations that Spacey sexually exploited or assaulted numerous underage men.

Plummer is, to put it bluntly, the rare famous male whose career has benefited from the "Weinstein effect." He is also enthusiastically supportive of the public reckoning around sexual misconduct that followed. "I think it's great—of course I do," he says. "The people who have [perpetrated harassment] are just disgusting. I'm not a prude by any manner of means, but they must be so insecure. Why would a good-looking man like Charlie Rose, for example—why would he have to go through all that to be a successful lover, for Christ's sake? There's something awfully wrong. I think it's fantastic that the girls are now feeling free to come forward."

Having worked in entertainment longer than Spacey has been alive, Plummer recognizes how he has benefited from the old system of exclusion, particularly on the stage. "I played all the great parts in the theatre," he says. "Now the women are coming, and they're going to play all the male parts—in Shakespeare, for example." He chuckles. "I'm glad I played them all already, before the women came to town!"

Plummer expresses annoyance just once during our morning together. "God, this whole fucking interview is going to be about The Sound of Music!" he groans. (Then he chuckles just lightly enough to reassure me I won't be banished into the woods of Connecticut.)

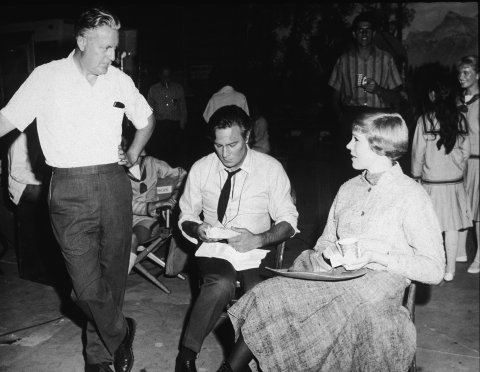

I had perhaps gone on about it too long. Plummer played Captain Von Trapp, starring alongside Julie Andrews in the beloved 1965 musical. The role remains his most famous, though it's far from his best work. It's also one he regards with a fluctuating level of irritation. He has been known to refer to it as "The Sound of Mucus," or "S&M."

"It's just.... It lingers," Plummer explians. "Once you were given that Von Trapp image, then all the scripts came with the same kind of uptight son-of-a-bitches, and they were so dull and boring. I couldn't wait to be a character actor! So boring, being a leading actor, God."

He and co-star Andrews (with whom he maintains a close friendship) had no clue the film would become as monolithic as it did, and he admits he misbehaved on set in Austria. "I was so arrogant. I was young. I just loathed [the part]. I don't know how [director] Bob Wise stood me. He always said that I gave him the idea of not being too sentimental."

Still, the film opened the door to lots more film roles. He was 35 at the time, a renowned Broadway master initially uncomfortable acting in front of cameras. Music (or Mucus, if you prefer) made him an icon. Ten years later, he received the most memorable directorial advice of his career, from the filmmaker John Huston, who directed The Man Who Would Be King. Plummer played the author Rudyard Kipling, the film's narrator. At one point, he discovers the severed head of Sean Connery's character. "I'm talking to the head," says Plummer. "And I have a line. It was full of emotion. I couldn't say it right." Huston, whom he imitates now with a gravely croak, commanded, "'Chris! Just take… the music… out of your voice!'"

It was a breakthrough moment, teaching Plummer to avoid mawkish overemoting, and he's been underplaying the hell out of every role since. Given his plummy voice, regal looks and timeless demeanor, that meant a couple of decades of playing a lot of famous dead guys: Kipling; Franklin D. Roosevelt; Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington. Plummer's filmography became a survey course in enacting history.

And then, just before his 70th birthday, the renaissance began. It was the year he contributed a dazzling performance as newsman Mike Wallace in Michael Mann's sprawling whistleblower drama The Insider. Roles in A Beautiful Mind and Spike Lee's Inside Man, among other films, followed. He received his first Oscar nomination in 2010 for playing Leo Tolstoy in The Last Station, livening up literary squabbles alongside Helen Mirren as his wife.

To any floundering artist who feels like a failure at 30, consider this confirmation: Youth is overrated. Or perhaps youth is eternal, if you can summon the vitality and wherewithal and unknown devilry to remain creatively vibrant at 88. "I don't feel old, to start with," Plummer says. "You're sort of branded old suddenly."

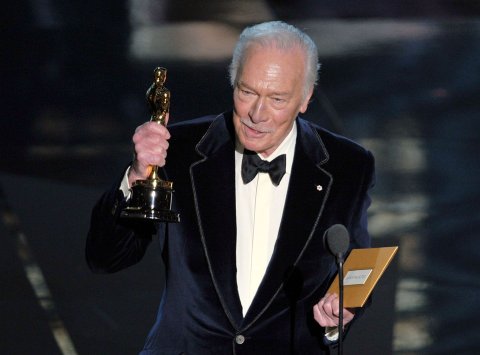

It was disorienting, for instance, when, at 82, he became the oldest actor ever to win the Academy Award for best supporting actor. "I thought, Oh God. I better behave!"

That prize was for Beginners (2011), an inventive romance co-starring Ewan McGregor. Plummer plays his older gay father, who decides to come out—and find a boyfriend—after his wife's death. Plummer's performance here is the photonegative of his ornery J. Paul Getty, so full of tenderness and zeal and—yes—unextinguished sexuality. And though he had never before had occasion to portray a queer romance onscreen, "I felt extremely natural in it," he says. "There was no angst or nerves or anything."

From there, the roles kept coming—the wealthy patriarch in Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Ebenezer Scrooge in The Man Who Invented Christmas, the dope-smuggling grandpa in Boundaries. I ask how he settles on the parts he chooses; surely he can't say yes to everything? "Well, I can try," he retorts. "When you're a great age—and they all keep reminding me how old I am—it's the healthy thing to do. You've got to keep working. And I love it!"

There are no plans to slow down or retire. "No, no!" the actor says. "Can you imagine what it's like to retire? Some friends of mine [have retired] and they're just absolutely ruined as people. They just... die. They fall apart. Go away. Awful." His plan is to continue working as long as the business keeps him young. "I'm going to drop dead on the stage, I hope."

Filmmakers who work with Plummer are dazzled by his energy. The crew on Boundaries kept making preparations because of Plummer's advanced age, Feste says, but "by day three we realized that was completely unnecessary. Christopher was memorizing 12 pages of dialogue a day. And he was a jokester on set." (He also entertained the cast, playing classical piano and, according to Feste, identifying any composer's music by ear.)

Practicing piano and playing tennis (there's a court within view) keeps him youthful, he says. But so does working. Plummer has a performance coming up with the Toronto Symphony, called Christopher Plummer's Symphonic Shakespeare (he recites, they play). And he's in talks to play another "famous, real man," though he's mum about specifics.

Every new decade seems to bring a Plummer resurgence. "It's a new career. It's terrific!" he laughs. "Maybe [in my] 90s I'll turn into a woman and play all the great parts again!"