The first letter Nawal el-Sayed El Saadawi ever wrote was to God. In it, the 7-year-old El Saadawi asked why—if God was just and fair—he had not made her mother and father equal. Since she had first learned to write, she had always included her mother's name, Zaynab, next to her own. But her father said it was his name, Sayed, that she must use, along with that of his father, Saadawi.

Saadawi never got an answer to her letter, and when her mother died—at just 45, having raised nine children—her name died with her. Unlike Saadawi's father, who could expect 72 virgins upon arriving in heaven, her mother was due no rewards, according to Islam, the faith of her parents. "A woman is without worth," she wrote in the first part of her autobiography, A Daughter of Isis, "on earth or in the heavens."

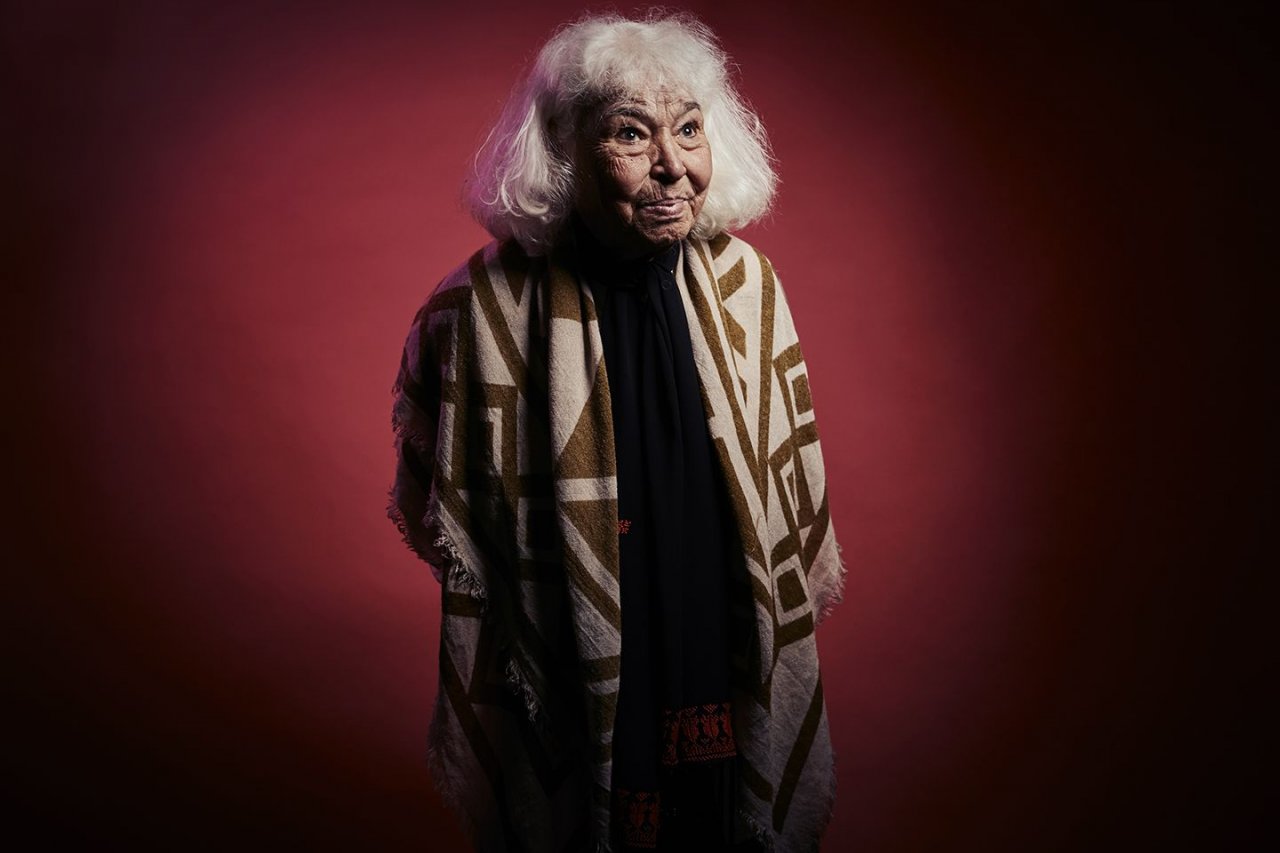

Saadawi, now 86, was not convinced by God then, and she isn't now: "The first letter in my life, I told God: If you are not fair, I am not ready to believe in you," she said during a trip to London to promote the reissue of her two-volume autobiography.

It is views like this that have ensured that Saadawi's life has been—in the words of her friend Margaret Atwood, the author of A Handmaid's Tale—"one long death threat."

Born in 1931 in the village of Kafr Tahla, Egypt, north of Cairo, Saadawi trained as a medical doctor before beginning her career as a writer in her 20s. She was fired from her job as director-general of Egypt's public health authority for her opposition to the practice of female genital mutilation.

Her 1977 book, The Hidden Face of Eve, included a harrowing account of her own circumcision at the age of 6 as her mother and aunts watched. It also outlined her opposition to the forced marriages of children.

One of her earlier books, a 1975 novel called Woman at Point Zero, told the story of a young woman, Firdaus, who becomes a prostitute in Cairo after fleeing an abusive marriage. After murdering her pimp and refusing to atone for her crime, she is sentenced to death. In the book, Saadawi painted a picture of Firdaus—who was a real person—as a feminist heroine who refuses to be cowed and, ultimately, dies free. "With each of the men I ever knew," Firdaus said in the final section of the novel, "I was always overcome by a strong desire to lift my arm high up over my head and bring my hand smashing down on his face."

And that included the most powerful among them. In 1981, Saadawi was arrested and jailed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, the military leader who had replaced Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970 and signed a controversial peace deal with Israel.

Her cellmates feared that Sadat would give them all the death penalty, but Saadawi was convinced she would outlive the president, which she did. In October 1981, a month after she was arrested, Sadat was assassinated at a military parade by officers opposed to his peace accord. But the Egyptian government was not the only institution angered by her work.

In 1991, Saadawi's name began appearing on "death lists" circulated by Islamist groups. The threats were not idle: In 1992, Egyptian writer Farag Foda was murdered by El-Gama'a El-Islamiya, the extremist group that carried out hundreds of killings during the 1990s. Saadawi's name was next on the list, and in 1993 she reluctantly left for the U.S., where she would spend the next 16 years in exile, returning to Cairo in 2009.

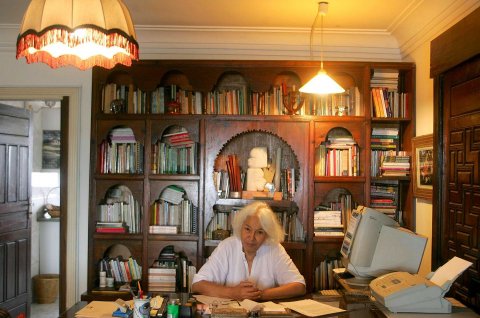

Offered a position at Duke University in North Carolina, Saadawi began her course on creativity and dissidence by telling her students she could teach them neither. "I said that I cannot undo what education did to you," she said, "how it makes people unaware why they are oppressed, of the causes in history, in the past, in the present."

Nevertheless, she strived to do so, starting with religion. Saadawi observed that from the time of Egypt's pharaohs—who ruled over Earth and the afterlife—religious and political power have been inseparable; there is no such thing as a secular state anywhere in the world. "[In Egypt] I was linking…religion to capitalism, to women's rights," she said. "So they had to stop me. I had to go to prison. They had to censor my work."

Above all, Saadawi said, religion is "silly. To believe that Christ came out of the grave and went to the sky, or he was crucified?" Saadawi laughed. "I spent 10 years of my life studying Judaism, Christianity, Islam, comparing the Old Testament to the New Testament to the Koran. I even went to India. I studied the Gita and Hinduism. The more you study religion, the more you see it is ridiculous."

During her time in the U.S., Saadawi saw Bill Clinton elected, followed by George W. Bush and then finally Barack Obama. When Hillary Clinton ran against Donald Trump in 2016, she was often asked about the prospect of the U.S. getting its first female leader, but—then as now—the question reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of her feminism.

"People ask: 'Would you like to have a woman ruler?'" Saadawi said. "It depends, because I do not divide people because of their genital organs. I don't say you are a man or you are a woman. There are men who are feminists and against oppression of women…and there are women like Clinton and [British Prime Minister] Theresa May and Condoleezza Rice who are more patriarchal than the men."

In 2011, Saadawi took part in the revolution that unseated Hosni Mubarak, leading to the elections won by the Muslim Brotherhood. Like many Egyptian leftists, she welcomed the downfall of the Brotherhood's leader, Mohammed Morsi, in July 2013, and objected to the use of the word coup to describe the military overthrow of his government. "I don't say 'coup.' The West says it was a military coup that removed the Muslim Brothers; this is not true," she said. "It was a revolution of the people."

Semantics aside, the four years since Egypt's General Abdel Fattah el-Sissi took power have seen a massive crackdown on human rights in Egypt, with thousands of activists—including liberals involved in the 2011 revolution, writers and Muslim Brotherhood members—now in jail. In 2018, Sissi won 97 percent of the vote after any real presidential contenders were banned from running or in prison.

Given that, does Saadawi still support the government in Cairo? "I support no government," she said. "I think no government really works for the people, in Egypt or in America. I don't believe in individual rulers, in kings, in [Margaret] Thatcher, or Mubarak, or Sissi, or Sadat, no. People cannot be ruled by one person. You need a revolution of millions."

Saadawi points out that while she is still forbidden from discussing female genital mutilation in the Egyptian press—though it's illegal, rates of female circumcision are as high as 87.2 percent in some areas of Egypt, according to the World Health Organization—she is a regular columnist for Al-Ahram, a state-owned newspaper. "That is a government paper, but I write in it. So there is progress. Under Sadat and Mubarak, I was censored."

And elsewhere in the world, other changes suggest reasons to be optimistic, she said, not least the #MeToo movement in the U.S., which began with allegations against movie producer Harvey Weinstein last October. (He was finally arrested and charged with rape by New York's district attorney in May.)

Watching events unfold from Egypt, Saadawi couldn't help but feel vindicated. "Those women, half my age, discovered what I discovered 40 years ago," she said. "I was linking patriarchy to class, to capitalism, to religion, to racism. When this #MeToo happened, I said, 'My God, how are they so late?'"

For years, Saadawi watched as Arab countries were portrayed as sexually repressed and backward, in contrast to the progressive West. "They thought that it is only women in Arab societies or in Muslim societies that are harassed," she said, "and that women in the U.S. and Britain are free. I was saying, 'No, we are all in the same boat.' I was saying that in the mid-'50s. They laughed at me."

As she spoke, Saadawi sketched on a piece of paper, writing down important words, underlining them, drawing diagrams that illustrate her arguments. When asked about the future, she turned the sheet over and drew a zigzag line. She was diagramming history: ups and downs, highs and lows, but always moving forward.

"We are here," she said, making a mark halfway down a decline. "That's why you have Donald Trump and May. We are in the period of fierce capitalism combined with fierce religious fundamentalism, together, and racism—you see how the Palestinians are being killed? It is a difficult period, but it will come to an end, because that is how history goes, in a zigzag line."