Like five of his modern predecessors, President Donald Trump inherited a growing economy when he moved into the White House last year—indeed, a record expansion from the depths of the Great Recession. But mere expansion was not "big league" enough for Trump. He promised to supercharge the economy, and, after Republicans passed a $1.5 trillion stimulus package, the task looked easy. His top economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, predicted "3 to 4 percent economic growth for as far as the eye can see." The president was no less gushing. "The Economy is raging, at an all time high," he tweeted, "and is set to get even better."

But here's the thing: It is not. And may not.

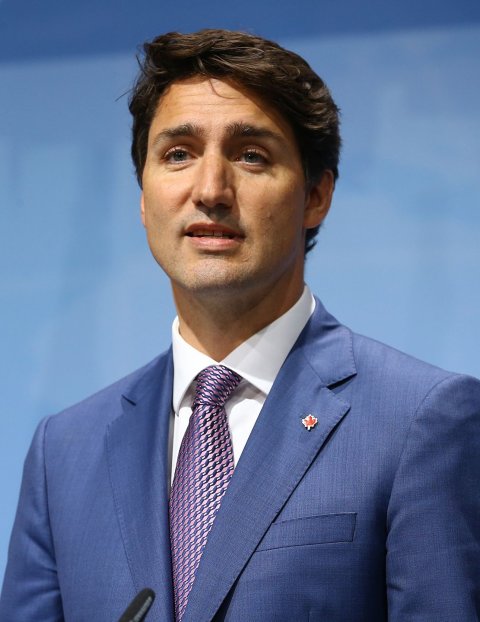

Although unemployment is low, inflation remains tame and gross domestic product (GDP) growth could, as Trump promised, exceed 3 percent for the second quarter, some economists have begun to dial back their rosy estimates. The reason: Trump himself. His "America First" agenda appears to be defeating his own goals. Policies such as corporate tax cuts that are designed to expand employment and investment rub against others that tend to do the opposite. (And that was before the president stoked an international trade war by imposing tariffs on foreign steel and aluminum and, earlier in June, insulted the prime minister of Canada, the country's second largest trading partner, calling him "very dishonest and weak.")

Take immigration. In the broadest terms, our economy needs population growth to fuel GDP. The math is simple. Consumer spending makes up nearly 70 percent of GDP: the more consumers, the more consumed. Yet the population is growing at less than 1 percent annually. If you choke off immigration, like imposing a "zero-tolerance" policy for people who enter the country illegally, growth becomes constrained, fewer households are formed, fewer goods are sold, and fewer jobs are created. The birth rate in the U.S. is at a record low, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meaning we aren't producing enough workers to replace the baby boomers who are now retiring. And in their retirement years, boomer spending decreases—until it ceases.

That's just the demand side. On the supply side, places such as Branson, Missouri, are struggling to find enough foreign workers for the busy summer tourist season because H2B visas (which permit employers to hire foreign workers, often seasonally) have been delayed or denied. What a delicious irony: A supposedly all-American resort town doesn't have enough immigrants to keep the music halls, restaurants and hotels fully operational. Seaside resorts from Maine to Miami have reported similar shortages.

Likewise, the housing industry can't build enough homes to meet demand. Trump's recent move to end Temporary Protection Status for nearly 60,000 Hondurans, for instance, directly affects construction in Texas and Florida. In Texas, 24 percent of Honduran TPS holders work in construction; in Florida, the figure is 29 percent, according to UnidosUS, a Latino civil rights and advocacy organization. That means new homes are more expensive because the inventory is low. Also boosting the price are rising mortgage rates, which have gone up as the Federal Reserve starts "normalizing" interest rates, and Trump's tariff on Canadian softwood, which has increased construction costs by $6,000 per home.

Meanwhile, U.S. immigration authorities have staged large-scale raids on the businesses of, among others, landscapers and meatpackers, rounding up hundreds of employees who lack proper work papers. While the visa restrictions and workplace raids fulfill Trump's promise to crack down on undocumented immigrants, the National Federation of Independent Businesses reports that more than one in three small businesses have job openings they can't fill, and nearly a quarter of them say it's their No. 1 problem. Ours too. The labor supply is projected to grow at just half a percent annually, according to the Congressional Budget Office; that's another foot on the GDP brake.

Nor has the $1.5 trillion tax cut done much to juice growth. Most of the cuts went to corporations and the wealthy—in the latter case, that's typical of tax cuts, since the wealthy pay the most taxes. But the corporations took their tax savings and bought back $178 billion of their stock from shareholders in the first quarter, as opposed to investing more of it in production or wages. Buybacks transfer wealth to shareholders, but remember that shareholders today are disproportionately upper-income households—more inclined to save than people earning the median $59,000 U.S. salary. "The notion that chopping off tax rates on the wealthy and companies will bring a riptide that lifts all Americans and fires up business investments has been utterly discredited," Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist for the Economic Outlook Group, tells Newsweek. "Yet, like a zombie, it keeps emerging from its grave."

In other words, the people who actually spend most of their earnings aren't getting a lot more to spend because wages haven't been growing much above inflation, despite the shrinking unemployment rate and the tax cuts. According to the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, workers need 3.5 to 4 percent wage increases annually to benefit from economic growth—a figure they haven't reached. Economist Lakshman Achuthan, chief operations officer of the Economic Cycle Research Institute, a consultancy, has noted that wage growth and spending growth are now easing—with consumers funding more of their spending with credit. "There is a stealth slowdown already happening," he told CNBC.

Trump's misguided obsession with the U.S. trade deficit further threatens growth. The prospect of a protracted trade war with Canada, China, Mexico and Europe is driving our global businesses nuts as the administration raises prices of steel and aluminum. They can't plan because cost estimates are all over the place. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is apoplectic. Meanwhile, free traders and protectionists within the GOP can barely disguise their contempt for each other. "What shall our friends make of such erratic behavior? How will they respond to such confusing actions?" asked Arizona Senator Jeff Flake, a traditional Republican free trader, in a tweet. Trump, of course, says that we can't lose a trade war. His rationale: With a $566 billion trade deficit, we're already losing.

But we can, in fact, lose, according to any economist not working for the White House. More than 1,100 economists, including 14 Nobel Prize winners, signed a letter to the president organized by the National Taxpayers Union; it warned that a trade war is a dangerous mistake. With a 25 percent tariff on steel and 10 percent on aluminum, for instance, consumers will pay $5.9 billion more as manufacturers pass along higher costs, according to a study by the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank. While the tariffs help metal workers specifically, they result in a net loss of jobs across the spectrum. In one analysis done by the Trade Partnership, a trade economics consultancy in Washington, D.C., the metal tariffs could cost the nation more than 400,000 jobs—more than 15 jobs lost for each metal job gained. As prices go up for finished goods that use steel and aluminum, such as autos, consumers will buy fewer of them. This leads to a cascade of bad outcomes, from declines in the service sector to job losses in manufacturing, that eventually lead to lower household spending on things like entertainment. It would clip 0.2 percent off of GDP in the short term, according to Trade Partnership.

Whatever trade inequities Trump seeks to redress—for instance, China dumping steel priced below cost on the U.S. market—business is more complex than winning and losing in a world of global supply chains and strategic partnerships. For instance, last November Goldman Sachs announced a $5 billion commitment with the China Investment Corp., that nation's investment company, to fund U.S. manufacturers that will sell goods to China. "These goods obviously being manufactured in the United States will create United States jobs," said Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein at the time. That kind of domestic investment is threatened when the administration promises tariffs on as much as $450 billion in goods from China, its largest trading partner. Faryar Shirzad, Goldman's global co-head of government affairs, notes that many U.S. exports can't simply be "put on a boat and sent across the water." The global part of global trade means companies like Boeing need assets and people in China as well as the U.S. You need to be partners to do that, not adversaries.

And we are creating adversaries at a time when we're going to need friends. Growth of the G-7 economies is clearly slowing. Predictably, Canada plans to impose $12.8 billion in tariffs, and Mexico $3 billion, on U.S. products. Those newly targeted goods range from pork—and 32 percent of U.S. pork exports go to Mexico, the U.S. Department of Agriculture says—to soybeans to steel, while the European Union is initially targeting $7.5 billion of goods, including motorcycles and bourbon. But instead of resolving his differences with world leaders at the June G-7 meeting in Canada, Trump escalated the trade war, making foreign cars his next big target.

Meanwhile, the combined tariffs imposed by U.S. allies will hurt American farmers and manufacturing companies such as Harley-Davidson—sectors that are a big part of the president's political base. Trump swept Rust Belt states like Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan in 2016, in part based on his promises to revive their industrial economies. Now, those places stand to bear the brunt of the pain from any retaliation.

Those risks don't seem to register with the president, who pronounced this "the best economy in the history of our country." Historians, economists—and perhaps his own supporters—may report otherwise.