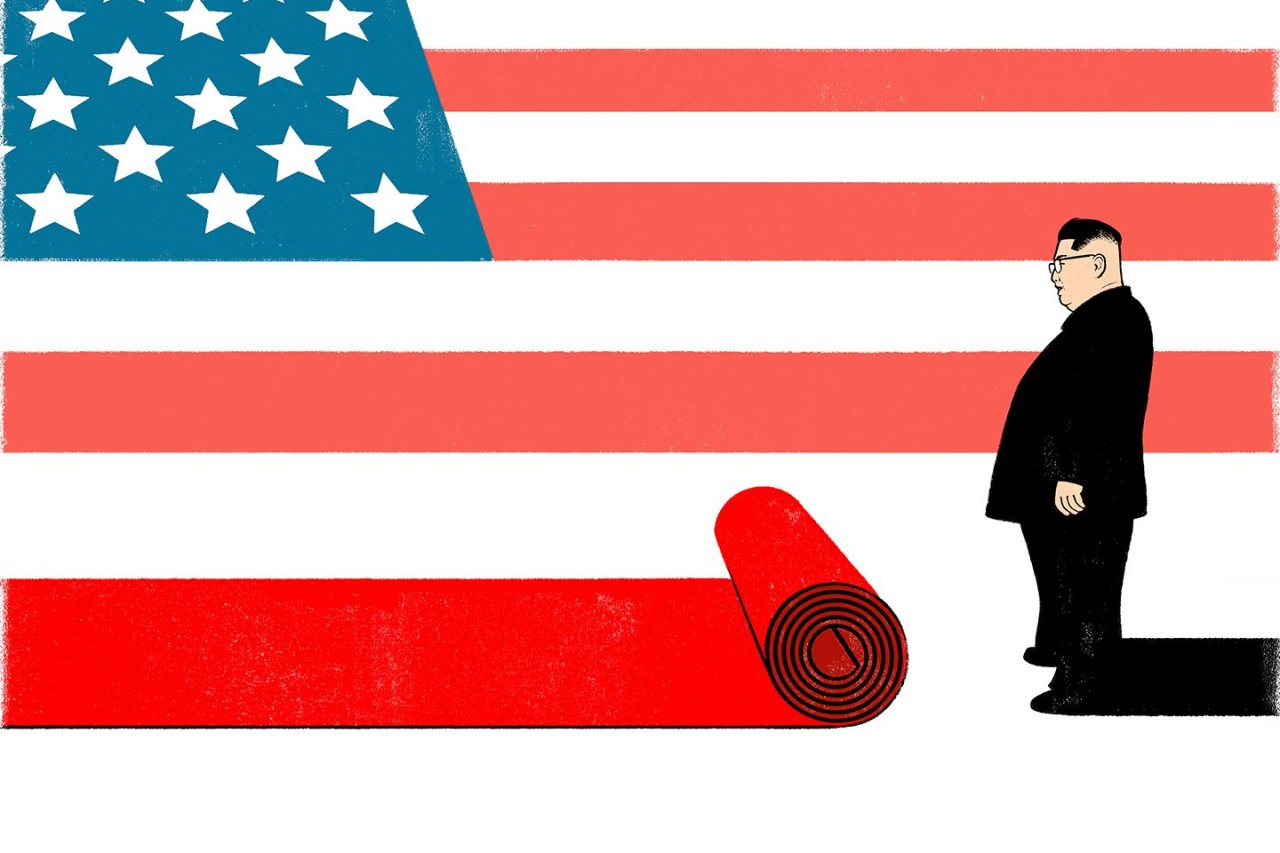

For more than six decades, U.S. presidents had a hard and fast rule when it came to North Korea: Don't meet with a dictator. The mere image of the leader of the free world standing with an authoritarian figure would bestow prestige and legitimacy on a rogue state—one that has flouted U.N. sanctions, assassinated political rivals and built a small nuclear arsenal.

Then, on June 12, Donald Trump burned the playbook. With full swagger, the president swept into steamy Singapore, where he sat down with Kim Jong Un in an unprecedented bid to get him to, as he put it, "de-nuke." Afterward, Trump dismissed the idea that his presence alone had given the dictator something precious. "If I have to say I'm sitting on a stage with Chairman Kim, and that's going to get us to save 30 million lives," Trump said, "I'm willing to sit on the stage. I'm willing to travel to Singapore very proudly."

As a candidate and now as president, there is nothing Trump likes more than being disruptive. North Korea, he reasoned, required such an approach. In his view, previous administrations had failed and then left him with a geopolitical mess. Indeed, outgoing President Barack Obama warned Trump that North Korea would be "the most urgent problem" he would face. "Thanks a lot for nothing, chief," is how one National Security Council (NSC) staffer, who was not authorized to speak publicly, characterizes the Trump team's reaction.

For nearly a year and a half, Trump blustered and threatened, and, for a moment, he even considered a pre-emptive first strike against the North. But he also got the U.N. to impose the toughest sanctions on the regime to date, and he got China, Pyongyang's economic lifeline, to restrict its own trade with its neighbor. As a result, Trump had apparently captured North Korea's attention in a way Obama never had.

At a meeting in March, Kim told South Korean officials he wanted to meet Trump. "There's no question that the economic pressure had a lot to do with it," says Cheong Seong-chang, senior fellow at the Sejong Institute, a Seoul think tank. The South Koreans relayed the message, and Trump, defying convention again, instantly accepted. The two sides agreed on a June summit date—hardly enough time, by traditional diplomatic standards, for aides to lay the groundwork for denuclearization talks.

Then came another unexpected round of name-calling, and Trump—to the horror of critics who said he never should have agreed to a meeting in the first place—called the whole thing off. When Rudy Giuliani, the former New York mayor who is now Trump's lawyer, said Kim came on his "hands and knees" begging the president to reconsider, he was roundly derided for speaking so bluntly in public. But even the president's national security staffers conceded Giuliani was right. "They wanted this more than we did," says another NSC official not authorized to speak on the record. The president recommitted.

And that is where things went awry. Trump saw the meeting as no big deal, a throwaway concession. In his view, he had Kim where he wanted him: on his heels economically, eager (if not desperate) to talk. The "deal" struck in Singapore would, at minimum, lay out a road map to complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization, or CVID, the shorthand that U.S. officials now routinely use. But, in reality, the master of the art of the deal might have gotten played. He gave something to Kim that the North Koreans have wanted for decades—an audience with the American president—and seemed to get little to nothing in return.

After their six-hour meeting, Trump emerged with a bland statement from Kim that simply said North Korea had committed to "work toward" the denuclearization of "the Korean Peninsula." The president assured the assembled press that he believed the North Korean leader would follow through, though he also conceded that maybe he would "stand before you in six months and say, 'Hey, I was wrong.' I don't know that I'll ever admit that, but I'll find some kind of excuse." Also benefiting from the summit was China, which had already begun to back off the sanctions it imposed on North Korea. Trump pledged to cancel military exercises with South Korea and mused about how he wanted to eventually withdraw all U.S. troops from the peninsula—something that Beijing would love, given its desire to dominate the neighborhood.

That's the post-summit irony: For all the fiery rhetoric and disruptive diplomacy of the past 18 months, Trump's administration is no better off than those of his predecessors. He's at the beginning of negotiations with an unreliable partner that analysts say probably never intended to part with its nuclear weapons in the first place.

Bill Clinton and George W. Bush traveled this road before giving up. Officials who have negotiated with North Korea in the past say it's not quite the diplomatic equivalent of hell, but it is something of a torture chamber. Christopher Hill, a career diplomat who led the so-called six-party talks in the Bush administration in 2005, says his North Korean counterpart, veteran diplomat Kim Gye Gwan, would often take breaks to "nap," then return to the meetings to say that Pyongyang's position had changed because he had "received new instructions." Hill got so frustrated at one point that he stormed out of the talks for three days. Only intervention from the Chinese restarted the negotiations.

John Bolton, now Trump's national security adviser, was under-secretary of state in 2002 when the same Kim Gye Gwan flatly denied a U.S. accusation that the North had a secret uranium enrichment program, only to have one of the diplomat's colleagues simultaneously confirm it.

That marked the end of the 1994 agreement painstakingly negotiated by the Clinton team, which was supposed to end the North's weapons program. Bolton, in a memoir of his time in the Bush administration, said the only thing that would lead to denuclearization in North Korea was an end to the Kim dynasty and "reunification" with the South. He also described negotiations with the North Koreans as "a miasma."

That is now where Trump finds himself. In Singapore, the president offered Kim security guarantees that ostensibly will keep Kim in power indefinitely, as long as he does "work toward" denuclearization. So regime change and reunification as the preferred route are out. As the direct talks unfold over the next few months—and they may include Kim visiting the White House around the time of the U.N. General Assembly meeting in September—the U.S., nearly everyone outside the administration believes, will have to rein in its expectations.

Privately, even doves in the government of South Korean President Moon Jae-in—who was the matchmaker in the Trump-Kim bromance underway—do not expect the North to give up its nuclear weapons program entirely. CVID is a nonstarter, but negotiations aimed at arms control are more realistic: getting the North to dismantle some aspects of its vast nuclear and missile production complex, and reducing the number of centrifuges spinning to enrich uranium.

This is the stuff of painstaking old-school negotiation. To the relief of everyone, Trump has successfully backed both sides away from the brink of war. We'll now learn whether his administration has the patience and the competence to follow through on the diplomatic opportunity facing it.