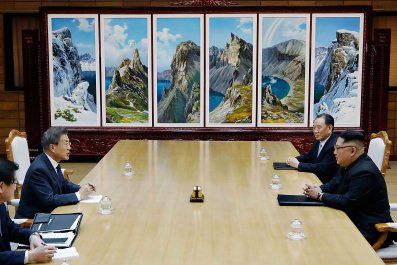

Long before President Donald Trump praised Kim Jong Un as the "very talented" and "strong head" of North Korea, his lovefest with Asia's authoritarian leaders was in full swing.

Last fall, the president invited to the White House Malaysia's then–prime minister, Najib Razak, known for jailing opponents, muzzling the media and allegedly running a kleptocracy. A few weeks later, he welcomed General Prayuth Chan-ocha, who toppled Thailand's democratically elected government in 2014. Soon after, Trump visited Manila, where he touted his "great relationship" with Rodrigo Duterte, ignoring questions about the Philippine leader's dismal human rights record.

Trump's open admiration of anti-democratic strongmen breaks with decades of diplomatic precedent and comes at a time when the administration is challenging traditional economic and military alliances; he has launched a trade war against allies in Western Europe, as well as Mexico and Canada, whose prime minister he recently dismissed as "dishonest" and "weak." Officials say the departure from political norms is part of the administration's policy of "principled realism," a clear-eyed assessment of U.S. interests guided by outcomes rather than ideology. As United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley once put it, the administration is "going to play with whoever we need to play with" to further American goals.

But critics say the policy ignores human rights and democratic ideals. They charge that, in Southeast Asia, it emboldens despots from Cambodia to Myanmar to feel they can oppress their people without fear of American intervention or sanctions. Many leaders in the region have even adopted Trump's own language to assert their authority; use of the term "fake news" is pervasive.

Michael G. Karnavas, an attorney based in The Hague who has appeared before the International Criminal Court, says Trump's embrace has given foreign governments the "green light" for atrocities. "Trump has emboldened these leaders to do and say as they wish," he tells Newsweek. "Human rights or the rule of law are not on his list."

For human rights advocates, among the most worrisome of these leaders is Duterte, sometimes called "the Trump of Asia." Elected in 2016, he launched an anti-drug campaign and enlisted police, the military and ordinary citizens to kill dealers, pushers, even users. Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 12,000 people have been slain in the drug war, including many who died in unlawful killings. The Obama administration condemned the assassinations, prompting Duterte to call President Barack Obama a "son of a whore."

By contrast, last November, when Trump met with the Philippine leader, he did not bring up human rights and, in fact, chuckled when Duterte dismissed the traveling press as "spies." (According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, at least 177 Philippine media workers have been killed since 1986, and Duterte himself has appeared to defend the assassinations, saying reporters are "not exempted from assassination if you're a son of a bitch.")

Duterte has also pushed to imprison one of his fiercest opponents, Senator Leila de Lima. She has been held for 15 months, awaiting trial on drug-trafficking charges. De Lima says Philippine law enforcement officials told her that the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration identified her as a drug lord, an accusation she fiercely contests. She tells Newsweek that she petitioned the U.S. Embassy for help. "I asked the ambassador if such a report indeed exists and for him to belie Duterte's claim if there is none," she writes from a Philippine prison. "I never got a formal reply to my letter. I think that generally describes the U.S. government's level of concern regarding my situation."

Analysts say U.S. ambassadors are silent because they have no clear direction from Washington. "It's hard for these ambassadors to take a stance, to speak out, and then your government doesn't support you," says Mohamed Nawab Osman, an assistant professor of international studies at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University.

In Cambodia, Prime Minister Hun Sen has steadily tightened his grip since he came to power 33 years ago. Last year, he shut down the Cambodia Daily newspaper, and an ally bought The Phnom Penh Post, leading Amnesty International to lament "the crumbling of Cambodia's media freedom." Hun Sen then abolished political opposition altogether: His Supreme Court declared the Cambodian National Rescue Party part of a foreign plot to topple the government, and his Cambodia's People's Party is now expected to sweep National Assembly elections on July 29.

While much of Hun Sen's repression predates Trump's own election, critics say the U.S. president has worsened matters with his own false allegations—that the feds have been spying on him, that special counsel Robert Mueller is pursuing a "witch hunt" against him and that the "disgusting" national media are out to get him. "How can the U.S. criticize the electoral process in Cambodia when Trump was claiming that the U.S. elections were rigged or that the FBI had spies in his camp?" asks Karnavas.

Hun Sen is clearly paying attention. Last year, when Trump blasted media outlets with "fake news awards," the Cambodian leader lauded the U.S. president. "I think President Donald Trump has correctly created an award," he said. In Thailand, Prayuth, now prime minister, insists an election will be held in February 2019, but that's the sixth election date he has

announced since ousting Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra in May 2014. In his October 2017 visit to the White House, Prayuth assured Trump an election date would be set this year but told media the president never asked and "it was me who initiated the discussion and assured him that Thailand will abide by its road map to return to democracy." Trump, he said, preferred to discuss investment and trade. Meanwhile, Prayuth has promised harsh enforcement of laws against "fake news and hate speech."

Perhaps Trump merely wants to focus on strengthening the 200-year friendship between the U.S. and Thailand, says Kan Yuenyong, executive director of Siam Intelligence Unit, a Bangkok think tank. "It's just getting back to rebuilding the old alliance," he tells Newsweek.

"I think Trump just wants to take a different approach from Obama."

Others argue that Trump is not deliberately abetting autocrats but instead unwittingly enabling them by neglecting the traditional American focus on democracy and human rights. "It is not a purposeful strategy or policy," says Bates Gill, a professor of Asia-Pacific security studies at Macquarie University in Sydney. "It's by dint of his inaction that bad situations have become worse."

When Malaysia's Najib visited the White House last year, his appearance came amid a Justice Department investigation into allegations that the leader, his relatives and cronies stole billions of dollars from a state investment fund. Trump, however, focused his remarks on trade, thanking the Malaysian leader for buying American equipment and committing one of his country's largest pension funds to investments in the administration's infrastructure effort. "Malaysia is a massive investor in the United States," Trump said during a photo opportunity, also praising the country for cutting business ties with North Korea. (The New York Times noted that the White House did move the picture-taking session from the Oval Office, "denying Mr. Najib the customary photo with the president before the fireplace, under George Washington's portrait.")

"With Trump, there's a certain cohesiveness in terms of ensuring the national interests of the U.S.," Osman says. "If there was nothing Najib could do to advance American interests, then Trump would have been more likely to talk about human rights."

Critics say Trump did not have the standing to hold Najib accountable. "If the U.S. president can lie with impunity, go after the press," Karnavas says, "why should heads of states where the rule of law is malleable not do the same?"

Eight months after the White House visit, Malaysians voted out Najib, apparently fed up with his autocracy and massive scandal. The former prime minister has denied all wrongdoing but is now being investigated by the new government of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. In the run-up to the election, Najib cried "fake news" to blunt criticism of his role in the embezzlement scandal, and his government adopted a law punishing purveyors of "fake news" with up to six years in jail.

A former U.S. diplomat based in Bangkok, who spoke on condition of anonymity, lamented the parallel: "They're all even sounding like Trump now."