When the world first learned of a historic summit between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, the news didn't come from a presidential tweet or a state-run media announcement. It came from a bespectacled South Korean official standing in the darkened driveway of the White House on a cool March evening.

In an impromptu appearance, Chung Eui-yong, South Korea's national security adviser, told the assembled press corps he had just come from a meeting with Trump. That week, Chung had flown to Washington from Pyongyang, where Kim had asked him to hand-deliver a personal letter to Trump. Kim, he told the media, had invited the American president to meet face-to-face to discuss an end to North Korea's nuclear program. And Trump had agreed.

Reporters were stunned. At the time, many people feared war. Trump had threatened to rain down "fire and fury" on North Korea, and Kim responded with his own threats to incinerate Washington with one of his long-range nuclear missiles. Now, Chung was announcing the first-ever meeting of a sitting U.S. president and a North Korean leader. "Along with President Trump," he said, "we are optimistic about continuing a diplomatic process to test the possibility of a peaceful resolution."

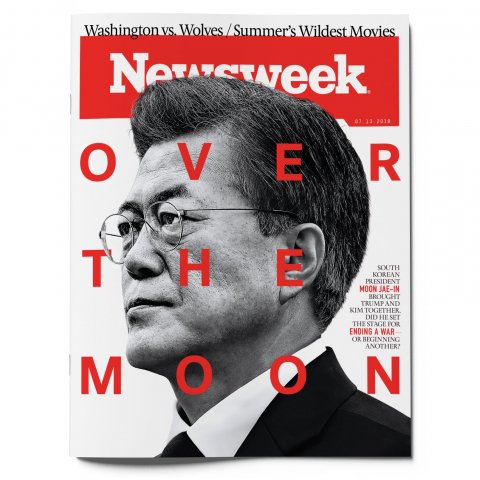

It's not clear why Trump gave Chung the job of publicizing the summit. But it was fitting that a South Korean official got to make the announcement. More than any other player in this diplomatic drama, South Korean President Moon Jae-in was most responsible for the historic meeting. Acting as mediators between Trump and Kim, he and his top aides had spent months encouraging, cajoling and flattering the two leaders into accepting the conditions that made their denuclearization talks possible.

For Moon, the Singapore summit was a diplomatic and political triumph. A joint statement reaffirmed the North's commitment to "work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula" and gave U.S. guarantees of security to North Korea. Trump and Kim also pledged to begin high-level negotiations to resolve their differences. In the wake of the meeting, polls showed Moon enjoying his highest approval ratings since his election in May 2017.

But Trump soon produced a couple of surprises of his own that could have devastating implications for the South Korean leader and his country. Most notably, he suspended joint military exercises with South Korea and reiterated his desire to lower Washington's defense costs by withdrawing all 28,500 U.S. troops from the Korean Peninsula. Intended as reciprocal goodwill gestures toward Pyongyang, the U.S. president's moves blindsided Moon and weakened South Korea's security, some analysts say. Meanwhile, some U.S. officials have raised doubts about Kim's sincerity; NBC News recently reported that North Korea had increased production of enriched uranium for nuclear weapons in recent months, even as it pursued diplomacy. Critics in both Washington and Seoul are now nervous that Moon has set the stage for a diplomatic process that puts South Korea's fate in the hands of an unpredictable American president who could leave the country vulnerable to the North and China by cutting a deal that removes U.S. troops from the peninsula.

"When Moon became the catalyst for shifting the whole discussion from war to peace, he was the man of the hour," Sue Mi Terry, a former CIA Korea analyst now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, tells Newsweek. "Now, he's finding that he's not driving this train."

As the U.S. and North Korea prepare for continued denuclearization negotiations, the stakes for Moon couldn't be higher. Disarming the North would cement his legacy as a power broker who helped upend decades of stalemate and usher in a new era of peace for the two Koreas. Failure, however, could cost him the presidency—and revive the threat of a war that almost certainly would devastate greater Seoul and its 25 million people.

Life on a 'Razor's Edge'

Moon, 65, has said he decided to become president and make peace with the North in 2009, when, as a senior official in the progressive Democratic Party, he met with his role model, former President Kim Dae-jung. The ailing Kim, who won the Nobel Peace Prize as the first South Korean president to visit Pyongyang, implored his protégé not to abandon his so-called Sunshine Policy of engagement with North Korea. A few days later, Kim died. "That was the moment," Moon told reporters last year. "He spoke those words as if they were his last will."

But Moon, who was born in a refugee camp at the end of the Korean War to parents who fled the North, formed his liberal sensibilities much earlier. As a law student, he chafed under his country's succession of authoritarian leaders, who took a hard line against North Korea. Moon became an outspoken student activist, earning a stint in prison for leading pro-democracy protests. Upon his release, he was conscripted into the South Korean army.

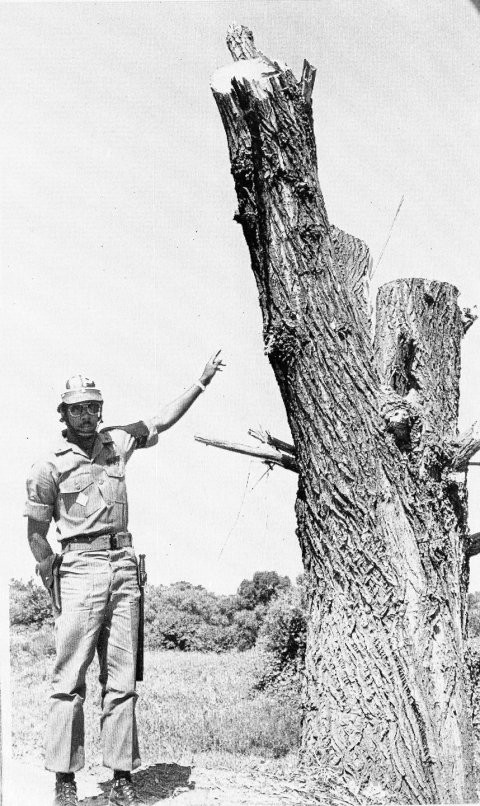

In August 1976, Moon, by then a squad leader in the special forces, got a close-up view of just how tense relations were between the two countries—and how quickly circumstances could flip from quiet to crisis. One morning, North Korean soldiers used axes to brutally murder two U.S. military officers overseeing a tree-trimming operation in the Demilitarized Zone, a narrow strip of rugged territory that separates the two Koreas. The North Koreans' commander had argued that the tree, which blocked the view of a United Nations observation post, had been planted personally by their nation's leader, Kim Il Sung. The incident made international headlines, and, in a flash, the 23-year-old armistice between the U.S. and North Korea teetered on the verge of collapse. President Gerald Ford ordered a second work party to remove the tree entirely.

Moon was part of a force of more than 800 U.S. and South Korean troops who accompanied the crew. As they entered the DMZ, Cobra helicopter gunships and nuclear-capable B-52 bombers circled overhead. Offshore, the aircraft carrier USS Midway steamed into position for potential airstrikes. "We were a razor's edge from one misperception or one bad judgment" plunging the Korean Peninsula into war, Van Jackson, a Korea expert at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, told The Atlantic.

Using chainsaws, the Americans and their allies reduced the tree to a stump. Outnumbered and outgunned, the North Koreans kept their distance. But for Moon, the memory of that day never faded. "That's when my view of our country and security, as well as my patriotism, were formed," Moon told an interviewer last year, just before he won the presidency.

After military service, Moon worked as a human rights lawyer and activist for the Democratic Party. He entered politics in 2003, serving as chief of staff to another political mentor, President Roh Moo-hyun, who also believed in a conciliatory approach to North Korea. In 2007, Pyongyang's weapons tests derailed Roh's outreach policy, reminding South Koreans once again of the threat posed by the North. But Moon never abandoned his hope for reconciliation.

The Matchmaker

When Moon won the presidency in May 2017, after an unsuccessful run in 2012, Kim Dae-jung's words still rang in his ears. He reversed the hawkish approach of his conservative predecessor, Park Geun-hye, and reached out to the North.

But Moon's approach soon bogged down as Trump and Kim hurled insults and threats of nuclear annihilation at each other, and the North Korean leader ignored Moon's repeated pleas for dialogue. In one of Trump's tweets, the president even rebuked Moon for his "talk of appeasement" with North Korea, chiding, "They only understand one thing!"

But in January, with the Winter Olympic Games in South Korea looming, Kim suddenly responded to Moon, offering in a speech to open a dialogue with the South. Moon seized the opportunity. Northern and Southern officials crisscrossed the DMZ to discuss North Korea's participation in the games. At the opening ceremony in February, athletes from both countries marched into the stadium under one flag depicting a unified Korean Peninsula, suggesting a thaw in their geopolitical standoff. Another promising sign was the presence in the viewing stand of Kim Yo Jong, the younger sister of the North Korean leader. The two Koreas even formed a unified women's hockey team to compete in the games.

After the games, officials from the two countries continued to exchange visits amid the escalating rhetoric from Trump and Kim. It's unclear who came up with the proposal for a Kim-Trump summit, but the idea soon developed. The two sides agreed that Chung, one of Moon's closest aides, would deliver the invitation to Trump.

As U.S. and North Korean officials discussed where their leaders would meet, Moon and Kim held their own summit in the DMZ's so-called Joint Security Area, only the third time leaders from North and South Korea had ever met since the country was divided in 1945. The two leaders warmly held hands and planted a tree not far from the site of the ax murder incident. And in their one-on-one talks, according to South Korean officials, Moon persuaded Kim to commit to denuclearization in his summit talks with Trump, arguing his country would never find relief from crippling international sanctions as long as he retained his nuclear arsenal.

Moon also flew to Washington and urged Trump to offer Kim security guarantees and economic incentives at their summit to convince Kim that his regime would be safe without nuclear weapons, U.S. and South Korean officials say, speaking on condition of anonymity in order to discuss sensitive diplomatic matters. In later discussions, these officials said, Moon implored Trump to allow for a gradual process of denuclearization. And he persuaded Trump to ignore hard-liners like national security adviser John Bolton, who pushed to overthrow Kim unless he agreed to surrender all his nuclear weapons and bomb-making infrastructure up front.

Familiar with Trump's outsized ego and short attention span, Moon flattered him to keep him on board, telling the U.S. president that a summit with Kim would earn him a well-deserved Nobel Peace Prize—a suggestion that Trump treasured so much that it became a chant at his rallies. And when Trump briefly canceled the summit after a senior North Korean official branded Vice President Mike Pence a "political dummy" for repeating Bolton's regime-change threat, it was Moon who rushed back to Washington and persuaded Trump to stay the course.

Kim provided an added push to Moon's diplomacy by following through on a promise to destroy his only known nuclear test site. Critics have questioned the value of the gesture, noting his previous nuclear tests had already all but wrecked the site. They also noted that North Korean officials removed all sensitive equipment before detonating explosive charges, suggesting Pyongyang was hedging its bets in case denuclearization talks broke down. While some U.S. officials have portrayed Kim as deceptive for producing more nuclear fuel, he could also be jockeying for position in advance of negotiations: The more fuel he has, the more chips he can trade for economic aid.

The End of 'War Games'

Skeptics in Washington have flayed Trump for his performance at the Singapore summit. "The joint statement is a decidedly underwhelming document, consisting largely of generalities and platitudes that Trump quickly tried to oversell," says Jonathan Pollack, an East Asia specialist at Washington's Brookings Institution. Even worse, some analysts argue, was Trump's decision to halt military exercises with South Korea. For the U.S., it denied Secretary of State Mike Pompeo leverage when he begins the denuclearization talks with his North Korean counterpart. And for South Korea, it removed Seoul's strongest reminder of allied military might against Pyongyang. South Koreans, says Terry, the former CIA analyst, "are finding that some of the things they need to count on, like the alliance and the U.S. military presence, are not as solid as they thought."

But Moon's aides dispute that view, noting Trump's halt to what he called "provocative" military exercises is entirely consistent with the South Korean leader's previous calls on the U.S. to curtail them to avoid antagonizing the North, which has always viewed them as threatening "war games." Indeed, in May, when Trump was still exerting what he called "maximum pressure" on North Korea, South Korea bowed out of a planned joint-training exercise involving U.S. B-52 bombers, saying it risked stoking tensions in advance of the June summit between Trump and Kim.

Despite criticism from conservatives, Moon has stood by Trump and his decision to suspend the joint exercises. "We believe there is a need to consider various ways to further promote dialogue as long as serious discussions are being held between the United States and North Korea for the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and establishment of peace," South Korean presidential spokesman Kim Eui-kyeom told reporters.

William McKinney, a former top Korea specialist for the U.S. military's Pacific Command, notes Pyongyang has good reason to feel threatened by some of these joint military drills. Described by the Pentagon as "decapitation" exercises, past drills have involved nuclear-capable American stealth bombers, ballistic missile submarines and as many as 350,000 U.S. and South Korean troops. During recent exercises, the U.S. even launched a pair of unarmed intercontinental ballistic missiles from California's Vandenberg Air Force Base, dropping them into the waters just off the North Korean coast in a pointed display of U.S. strategic capabilities.

In a commentary for 38 North, a website that focuses on North Korea, McKinney wrote that because of the "highly provocative" nature of the exercises, "[Trump's] surprising commitment [to suspend them] is the most strategically significant confidence-building measure that could be made."

Moon now appears to have achieved two key goals of his engagement policy: direct talks between the U.S. and North Korea and a reduction of military tensions between the two adversaries. And as a result, he's enjoying widespread popularity at home.

In recent local elections—broadly regarded as a referendum on Moon's policies—his ruling Democratic Party swept 11 of 12 parliamentary contests and 14 of the 17 major gubernatorial and mayoral races. A poll taken after the summit gave him a 79 percent approval rating, the highest of any of South Korea's democratically elected presidents after a year in office. "The South Korean government seems to be very happy," says Victor Cha, President George W. Bush's top adviser on Korean affairs.

U.S. Alliances in Doubt

Still, the celebration could be short-lived. Lasting peace, experts say, rests on a number of unpredictable situations. Topping the list are the upcoming denuclearization negotiations, where U.S. and North Korean teams will try to flesh out the Singapore statement with timetables for dismantling Kim's nuclear arsenal of an estimated 65 bombs and the economic relief the U.S. will provide in return. A senior U.S. defense official says the U.S. will soon present "specific asks" under a "specific timeline" to Pyongyang, whose response will clarify North Korea's level of commitment. "We'll know pretty soon if they're going to operate in good faith or not," the official told reporters, asking not to be named in order to discuss a sensitive issue.

If past negotiations with North Korea are any guide, all manner of misunderstandings could cause a breakdown. In 2005, Pyongyang pulled out of a denuclearization agreement, accusing the George W. Bush administration of bad faith after it slapped the North with new economic sanctions just days after the deal was signed. A 2012 agreement restricting North Korea's nuclear and missile tests fell apart when North Korea insisted that long-range missiles for satellite launches were exempt.

Challenges for Moon are almost certain to arise over the future of the U.S. military presence in South Korea. A fierce debate between Moon's supporters and South Korean conservatives erupted over the issue in April, following Moon's meeting with Kim. At the time, the two leaders agreed to pursue a peace treaty that would formally end the Korean War. In response, Moon Chung-in, an unrelated senior adviser to the South Korean president, suggested U.S. troops might have to withdraw from South Korea if a treaty were signed. "It will be difficult to justify their continuing presence in South Korea after its adoption," the adviser wrote in Foreign Affairs.

Conservatives protested that such talk played into Pyongyang's hands, weakening South Korea's leverage in peace negotiations with the North. These critics also challenged Trump's boast, tweeted after the Singapore summit, that the nuclear threat from Pyongyang had ended. "To the contrary," Cho Young-key, a senior fellow at the Hansun Foundation, a conservative think tank in Seoul, told The Wall Street Journal. "They have reaffirmed the completion of their nuclear weapons program multiple times this year."

Trump's talk in Singapore about the money the U.S. would save by bringing the troops home has reverberated in Washington. Some analysts now warn China would be the biggest winner of any such withdrawal, and America's East Asian allies—South Korea and Japan—would suffer by losing the guarantee of U.S. protection, the central element of their respective alliances with Washington. "China would like to see a reduction in [U.S.] military forces in Northeast Asia and a widening of the gap between the United States and its allies and partners," says Ryan Hass, an East Asia specialist at the Brookings Institution. "Beijing is now on track to achieve these objectives at little cost."

For Moon and his country, the risks are serious: a nuclear agreement that shortchanges South Korean security in a region dominated by China; or no agreement at all, another war of words, and possibly one involving nuclear-tipped missiles. The South Korean leader, however, considers such talk wildly premature. With North Korean denuclearization still in its infancy, it could be years before the peace process that he began ever reaches the point where it's considered safe to bring home U.S. troops from South Korea. So for now, Moon is focusing on the small steps that will keep the process moving forward.

On June 22, the Pentagon announced that, in coordination with senior South Korean officials, the U.S. military had "indefinitely suspended" major military exercises on the Korean Peninsula. A few days later, North Korea canceled its annual "anti-U.S. imperialism rally," one of the largest and most politically charged events on Pyongyang's calendar. North Korea also recently informed the White House it would soon return the remains of more than 200 American soldiers missing since the end of the 1950-53 Korean War.

Meanwhile, North and South Korea are working to reduce their own tensions. Among the first items for consideration: the removal of weapons from an area of the DMZ, where, more than four decades ago, Moon witnessed how a squabble over an overgrown tree could lead two nations to the brink of war.