A blow-dryer hot wind distorted the microphones as Arizona Representative Martha McSally and Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen took their places at an outdoor podium in the Sonoran Desert. It was late May, and the two stood under the baking sun on sandy soil near a section of steel border wall in Nogales. "If you crossed the border illegally with your family, we take the parents, and we prosecute them," Nielsen said, as U.S. agents were separating parents from children from Tijuana, Mexico, to McAllen, Texas. "People seem to think there should be no critical consequences if they have children." A cluster of TV cameras and a crew from the Spanish-language Univision recorded the scene.

As chair of the Homeland Security subcommittee on borders, McSally had invited Nielsen to meet with "border stakeholders." With the wall and a few ranchers in 10-gallon hats as backdrop, and border patrol helicopters maneuvering above, Nielsen responded to a question about family separations, which were just beginning to penetrate the national news cycle. She said incoming families contribute to "lawlessness and insecurity at our borders" and classified the children as fake news. "In the last couple of weeks," she said, "there has been a massive dishonest misinformation campaign by people who do not want to see our borders secure."

McSally, standing nearby in blue jeans and boots, looked pained and uncomfortable. Although the press conference fell within her purview as a subcommittee chairman—and it gave her a chance to look hawkish on the so-called border crisis in her run to become Arizona's new senator—it was the voters of the mostly immigrant-friendly Tucson area who had sent her to Washington. So when reporters moved in to ask about the family separations, she dodged, summoning an aide to corral the media behind the windows of a U.S. Border Patrol press bus.

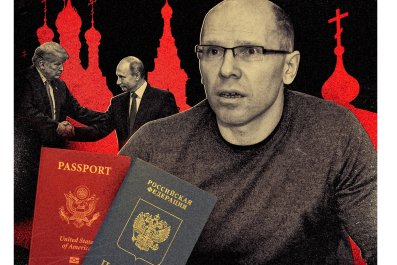

In normal political times, a woman with badass military cred who leans right-center would make an unbeatable Republican candidate in Arizona. McSally was the first female to fly in combat—she helped enforce the no-fly zone over Iraq in the 1990s—and the first woman to command an aviation squadron of fighters and bombers. She retired from the Air Force in 2010, after earning a Bronze Star and six air medals. Her district elected her as a moderate Republican in 2014. She supported citizenship for the young undocumented immigrants known as Dreamers and later opposed Donald Trump's presidential run.

But these are not normal political times. In 2018, the Republican Party belongs to Trump. The president began remaking the GOP from the ground up during his campaign. He cracked the Overton window, or range of appropriate discourse, and, in stumping for nationalism and against liberals and intellectuals, opened the door to the so-called alt-right and fringe conspiracy theorists. Supporters of the GOP, once the staid party of fiscal responsibility and conservatism, watched in disbelief as he was elected, then fell in line.

And now Republicans, like a mule with a burr, are stuck with Trump. To be sure, the president has accomplished many of the GOP's goals: tax cuts, deregulation and, very likely, a Supreme Court that could overturn Roe v. Wade. But his foreign policy decisions have decimated the pro-NATO and pro-coalition stance of both President Bushes, and his tariffs run counter to traditional free-trade policies. Still, few Republicans campaigning today could possibly publicly disagree with him and survive. Not when Trump will eviscerate critics on social media, and not when polls reveal that 90 percent of Republicans are behind him, even after the polarizing child separation headlines in June.

While his nativist influence has, arguably, made the party a happier home for racist or fringe-courting candidates—in Illinois and Virginia, for example—his popularity means even moderates running in the midterms have to move to the right to appease his base. Supporting Trump doesn't always mean victory, especially when candidates have other baggage—Alabama Judge Roy Moore, for example, was accused of sexual misconduct and lost a Senate race—but loyalty to the president has been a decisive factor in GOP primaries across the country, from South Carolina to California.

And it's Trump's immigration agenda, more than any other issue, that's galvanizing Republican voters, dividing Arizona and redefining the national GOP. McSally's main opponents for the party nomination are Kelli Ward, an osteopath, former state senator and self-described "build-the-wall, stop-illegal-immigration Americanist," and Joe Arpaio, the polarizing former sheriff and immigration hard-liner who made a national name for himself forcing prisoners to wear pink underwear and bake in an open-air tent city in the Arizona desert.

As summer approached, McSally was feeling more than the record-breaking Phoenix heat on her bid. In March, Ward and Arpaio headlined a Trump unity rally in northern Phoenix, speaking to a crowd packed with members of militias and other organizations that the Southern Poverty Law Center characterizes as hate groups. The anti-immigrant Patriot Movement AZ organized the event. Its members had distinguished themselves at the Arizona Capitol earlier this year by shouting "Illegal!" and "Go home!" at people of color, including a Navajo state representative.

McSally did not attend the unity rally, but she was busy burnishing her Trump bona fides. That same month, she not only affirmed her support for a wall between the U.S. and Mexico but suggested that one might be necessary between Arizona and California to "protect Arizonans" from the Golden State's "sanctuary cities." She also withdrew her name as a co-sponsor of legislation that would create a path to citizenship for Dreamers and scrubbed her website of a YouTube video in which she challenged then–Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly about their safety if Trump were to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

With the border show in May, McSally's transformation seemed complete. She is now the favorite to clinch the Republican nomination in the August 28 primary. Establishment Republicans are pouring money into ads that portray her as a border hawk, including one featuring an ominous voice-over warning of "violent gang members putting us all at risk" over video of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arresting shirtless, tattooed brown men. One Nation, a Virginia-based nonprofit with ties to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and George W. Bush–era political mastermind Karl Rove, has spent a reported $500,000 on McSally ads running statewide.

Meanwhile, Ward's supporters are pushing back; the airwaves in Arizona have been saturated with dire warnings about a border crisis. In July, GOP mega-donor Robert Mercer pumped half-a-million dollars into a super PAC to boost the former state lawmaker. One of the group's ads casts McSally as a "never-Trumper" who is pulling off a "Hollywood acting job pretending to support" the president.

Whoever wins, one thing is clear: The Republican nominee, as in scores of contests across the country, will be molded in Trump's image. That such a development could happen in Arizona, the spiritual touchstone of modern conservatism, is more than seismic. It represents a dramatic repudiation of the kind of moderate Republicanism that guided the national party for decades and produced the last two major attempts at comprehensive immigration reform. Just five years ago, it was Arizona's senators, John McCain and Jeff Flake, who pushed their party to compromise on immigration in hopes of political renewal.

Today, McCain, sidelined with brain cancer, is lashing out against Trump from his ranch in Hidden Valley. Flake is retiring and giving floor speeches on behalf of a party that doesn't seem to care. And the candidates seeking to succeed him are spreading the kind of incendiary rhetoric that he spent a career condemning. For some Republicans, this Trumpification is a much-needed electric shock to a moribund party; McCain and Flake, they say, were long out-of-step with conservatives, especially on immigration.

But to others, all of this has the stink of political death. Just 44 percent of registered voters in Arizona approve of the job Trump is doing as president. Recent polls show Democratic Representative Kyrsten Sinema leading McSally, Ward and Arpaio by at least 7 points in the November general election matchup. A victory would make her the first Democrat to represent Arizona in the Senate in 30 years and the first from her party to win statewide in a decade. Both parties see the seat as critical to their control of the Senate.

"Let's say the Republican establishment gets McSally over the primary line," says Rodd McLeod, a Democratic political strategist in Arizona. "She will have spent the previous year running hard to the right and will have to spend 10 weeks trying to tell people, 'No, that's not really me.' Meryl Streep should watch out."

Or perhaps there will be no pivot at all. In 2018, it's all Trump, all the time.

Democrats hope for a "blue wave" in the midterms, and recent polls show they have a chance, especially with independents skeptical of Trump and moving away from the Republican Party. In November, Democrats face elections in 26 Senate seats; Republicans have nine. In the House—in some ways more crucial as the Mueller investigation rolls on and Democrats bray for impeachment—all seats are up for election, and Democrats need to take 24 of them from Republicans to control the House. Twenty-five of them are in districts Hillary Clinton won in 2016. The Democrats chances of taking the Senate are not as bright, but Arizona's race is testing Trumpism like nowhere else.

'It's Tribalism'

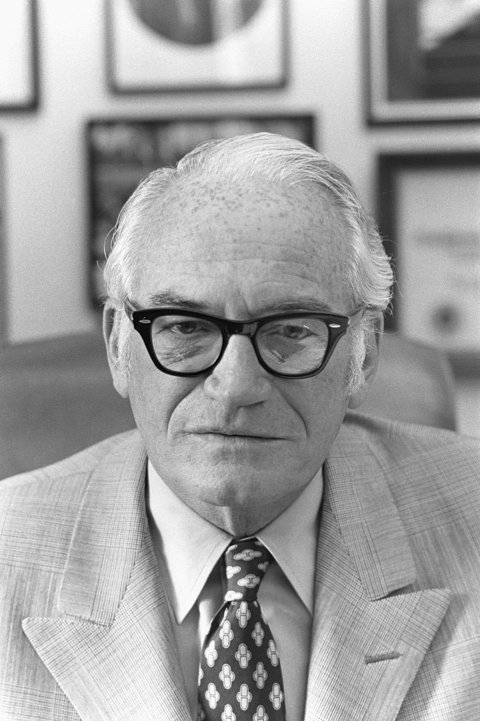

Arizona was reliably red long before the term red was used to denote Republican territory. It was home to Mr. Conservative himself, Barry Goldwater. The last time the state went for a Democratic presidential candidate was 1996, when voters backed Bill Clinton. Phoenix and its conservative suburbs are packed with GOP geriatrics in gated communities. And Tucson is a blue dot to the south. But the state as a whole is a demographic mélange of different sorts of conservatives: polite Mormons, veterans, alt-right biker gangs, libertarians and seniors who lean right but worry about their Social Security and Medicare. Voters who don't affiliate with either major party make up over 30 percent of the electorate.

At the same time, Arizonans have elected several notable Democrats to statewide office, as recently as former Governor Janet Napolitano in 2006, who went on to become President Barack Obama's homeland security secretary. Currently, four of Arizona's nine U.S. House members are Democrats.

Demographic change has fueled the platforms of both parties: Arizona has the sixth largest Hispanic voting population in the U.S., at 31 percent. And their numbers are growing fast. Between 2016 and 2017, Maricopa County's Hispanic population growth was second highest in the nation, after Harris County, around Houston.

Unsurprisingly, then, immigration has always been a dominant issue in the state, but attitudes vary widely. Polls consistently find two-thirds of Arizonans oppose the wall. At border towns like Nogales and Arivaca and even in Tucson—in McSally's district—it's easy to find residents who have worked with immigrants, who do business across the border and who support or belong to organizations like No More Deaths and the Samaritans, humanitarian organizations that medicate and even house dehydrated migrants. It's also easy to find people in the border area who will tell you that they have seen worse crises than the one talked of today. Ten years ago, residents of the tiny town of Arivaca say they would encounter hundreds of undocumented migrants stumbling out of the arid borderlands every week. Now, it's rare to see more than a handful.

But another hour north, on Interstate 10—which bisects Arizona before veering west to California—political sentiment changes with the terrain. The land flattens, the saguaro thin out. A farming culture here has shriveled in recent decades, replaced in the barren wastes of the Santa Cruz River Valley by two white compounds, sprawling and well-fenced: a private prison and a detention center for immigrants who entered the country illegally. Farther north, in populous Maricopa County, golden years communities are filled with people who worry about immigrant crime and favor a wall. And they vote—in big numbers. That has helped to fuel a Republican-dominated Legislature that passed one of the strictest and most controversial immigration bills in the nation: SB 1070 requires police to determine the immigration status of anyone arrested or detained based merely on "reasonable suspicion." Even McCain, the self-described maverick who bucked the fringes of his party, had to pander to the wall-loving minority to win re-election in 2010. ("Complete the danged fence," he said in an ad.)

While Flake cut a more moderate position on immigration (he was one of the "Gang of Eight," along with McCain, who spearheaded a failed immigration bill in 2013), he successfully navigated these waters for almost two decades, first as a congressman for 12 years and then in the Senate. He succeeded, in part, because his conservative credentials on other matters were rock-solid. "We've always had personalities, like Joe Arpaio, pushing immigration hard from the right," Flake says. "But it has always been enough to be fiscally conservative and pro-life. You were given a little more leeway on immigration."

Then Trump ran for president. He campaigned in Arizona seven times, with calls to "build the wall" and accolades for "Sheriff Joe," who was often standing by onstage. GOP voters loved it. While most Republicans in Washington remained silent, Flake went to war, becoming one of Trump's harshest critics. After the election, he wrote and published a book, Conscience of a Conservative, in which he reminisced about how migrant workers on his father's farm "worked harder than we did."

"Among those who were raised in rural Arizona," he wrote, "it is much more difficult to summon the vitriol for immigrants that fuels so much of the politics in the age of Trump."

Last August, Trump responded in kind. During a boisterous rally in Phoenix, he trashed Flake as "weak on borders, weak on crime." On Twitter, he saluted Ward for her primary challenge. Soon, former political strategist Steve Bannon endorsed Ward, as polls showed the incumbent senator trailing.

Eight weeks after the Phoenix rally, Flake announced his retirement from the Senate and delivered what sounded like a eulogy for a political party that now seemed unrecognizable. "We must never meekly accept the daily sundering of our country," he said, "the personal attacks, the threats against principles, freedoms and institutions, the flagrant disregard for truth or decency, the reckless provocations, most often for the pettiest and most personal reasons, reasons having nothing whatsoever to do with the fortunes of the people that we have all been elected to serve."

Flake tells Newsweek he chose not to run again because, given his antipathy toward Trump, he couldn't ask his supporters to volunteer and raise money for what would surely be a losing bid. "It used to be that when you polled Republicans about what was most important to them, they would say jobs and the economy. Now, if you ask that same question of Republican primary voters, the response is 'Are you with Trump?' That consumes everything. It's shirts vs. skins. Its tribalism."

Indeed, the classic conservatism of Arizona has been rattled like bleached cattle bones near a freight train in the desert. Not only is the state flipping a page on its political past, but so is America. The changes in Arizona represent not only the challenges of the Republican Party but the future of the country itself. "When immigration is everything, and the president makes it OK to ridicule Hispanics or to talk down on Mexicans, it allows this latent nativism to come to the fore," Flake says. "And you certainly see that now."

'I Finally Found My Hero'

Before Trump, there was Arpaio. The self-described "toughest sheriff in America" spent years unrepentantly racially profiling Hispanics in Maricopa County and jailing his quarry by the thousands. Pardoned by the president after he was convicted for contempt of court last year for failing to cease those practices, the 86-year-old sees an opening to a final political act.

Arpaio is currently running third behind McSally and Ward, spending little money and relying on the free advertising that he gets from his long history as a media showboat—a strategy not unlike the one Trump used in 2016. And with their shared focus on immigration (and their shared birthday—a fact Arpaio loves to emphasize) his strategy is straightforward: making sure everyone knows he was Trumpy before Trumpy was cool. "Two months ago, I woke up in the middle of the night, and I started thinking: Everybody talks about heroes—cops, firemen," he says. "But I never had a hero! And I woke up and said to myself, 'I finally found my hero, and that's the president.' And I'm not ashamed to say it."

He's not alone. This year's Memorial Day ceremony at the National Cemetery north of Phoenix was packed with Trump lovers. A field of tiny American flags fluttered beside 80,000 military graves. Men sported "Vets Before Refugees" T-shirts. Patriotic bikers, with MIA/POW flags on their handlebars, trash-talked McCain, a former Navy pilot who spent five years as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam. Vets with hearing aids in red "MAGA" hats wiped away tears as a Marine band played taps.

Tom and Louise Reed had come to pay their respects. The couple consider Trump's presidency God-ordained and want a border wall because they believe training camps for the Islamic State militant group are operating in the desert around Tucson, staffed by ISIS terrorists sneaking over the border. In general, they add, immigrants from Central America and Mexico are bad apples, "stealing and cheating. We need order, not chaos," says Tom, who works in trucking. He planned to vote for Arpaio or Ward.

Nearby, Air Force veteran and retired medical lab owner Joseph Fihn had no problem with legal immigrants—he employed a few Mexicans himself—but he thinks a wall is a good idea because "we don't need any more people coming in, especially MS-13 [the Salvadoran gang]." Fihn was also split, between McSally and Ward.

But Arpaio's story is a cautionary tale too. Even as Trump won Arizona and the presidency in 2016, Arpaio lost the sheriff's office he had held for a quarter-century. Progressives—funded with tens of thousands of dollars from billionaire George Soros—and fired-up Latinos had made his defeat a priority. "No longer will we be known by the notoriety of one," his challenger, Paul Penzone, a 21-year veteran Phoenix cop, told supporters on election night.

Hispanic turnout had been credited with pushing out Arpaio, but, ominously for the nativists, a later precinct analysis showed that support for Arpaio had cratered in reliably Republican areas.

'Arizona Can Turn Blue'

In April, a Democrat named Hiral Tipirneni ran in a special election for the open congressional seat in Arizona's 8th District, home to a sprawling Sun City retirement community. Early voting is widely used in Arizona, and in the lead-up to the election, nearly 60 percent of the ballots came from voters 65 and older. The terrain was considered so solidly Republican that Democrats hadn't fielded a candidate since 2012. But GOP leaders were stunned: While their party's nominee won, Tipirneni, an Indian-American immigrant, a woman and a doctor, lost by just 6 points. Republican outside groups had spent more than $1 million to defend a seat in a district that Trump had dominated by 21 points.

The margin was so striking that political analyst Dave Wasserman of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report wrote on Twitter that a 30- to 40-seat pickup for Democrats in the House would be a conservative estimate in the midterms; the party needs to flip 24 seats to take the majority in November. An Arizona political analyst, Mike Noble, was blunter: The result was noteworthy because older voters in the district are typically less likely to cross party lines than Arizona independents. "Republicans should not be hitting the panic button," he said at the time. "They should be slamming it."

Because the race was a special election to fill the remainder of a congressional term, Tipirneni will get another shot in November. Sitting at a Starbucks as outdoor misters cooled down silver-haired patrons, she says disaffected Republicans have been inviting her to speak and showing up at her town halls. She was even invited to address some members of an evangelical area megachurch (a move church leaders later criticized). "It wasn't even about Trump," she says. "They were talking about retirement security and health care and education." As for immigration and the border crisis, she says, "people don't think a wall is the answer. It is just a conceptual idea that makes people feel safer. And I have not met a single person who is in favor of sending back the DACA kids." (DACA is the program that shields young undocumented people brought to the United States as children from deportation.)

For many Democrats, however, it is only about the president.

"Trump terrifies me," says Rich Sands, an Uber driver who lives in Fountain Hills and walks his dog every morning in a neighborhood where Trump and Arpaio fans dominate. "What's happening in America terrifies me. And Arizona can turn blue."

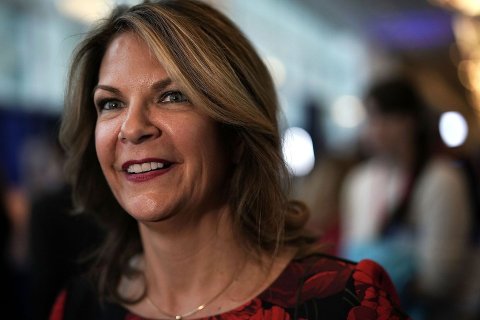

Sands was standing at Arizona's statehouse waiting for Kyrsten Sinema to file her candidacy papers for the Senate race. He planned to offer himself as a volunteer. The congresswoman strode in, clad in a white dress printed with hummingbirds. Her coiffed blond hair and red lipstick made her look like a 1950s movie star. Sinema's backstory is camera-ready too: She was raised Mormon but in a broken home; when her stepfather lost his job, the family lived for years in a gas station with no running water. She has said she is unaffiliated with any religion and is the first openly bisexual woman in Congress. She's also an overachiever: a triathlete with a law degree and a Ph.D. Time named her one of its "40 under 40" in 2010.

Like McSally, she has undergone a political transformation: She entered politics as a Green Party candidate and served three terms as a Democrat in the state House, where she developed a reputation as a liberal firebrand; she led a protest with Mexican-Americans and marched with Al Sharpton in opposition to SB 1070. She first ran for Congress and won in 2012, beating a Republican who accused her of practicing "pagan rituals" with no evidence other than her self-described atheism. Within two years, she was one of just four Democrats endorsed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Her district, the 9th, is affluent, mostly white and ideologically split between liberals in the university town of Tempe and conservatives in Maricopa County. She has made sure to support border security—short of the wall. Sinema was one of 24 Democrats to vote for Kate's Law, a Trump-era bill that punished foreigners for re-entering the country after deportation. She's also compromised with Trump where possible. Since 2016, she has voted with the president 60 percent of the time. Asked whether that record makes her any different from a Republican, she says: "If the president suggests an idea that's good for our state, I will support it." For example, she says, she has "worked together" with Trump to pass bills to help veterans. "But when the president suggests something that is bad for Arizona—like a trade war with China—I will oppose him. I'll take it as it comes." In a year animated by liberal antipathy toward Trump, such a statement of diplomacy by a Democrat is shocking.

But Trump did win Arizona, and Sinema is determined to play for the middle by shrinking the differences between herself and her GOP rivals on issues like immigration. While some of the leading figures in the Democratic Party call for the abolishment of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, she says it serves an "important function." She also bucked her party by joining with Republicans to back a bill to give federal authorities power to detain and deport noncitizens living in gang territory. The tagline on one of her ads: "Independent, just like Arizona."

Even where there are clear differences with the GOP, Sinema will flirt with rhetoric that would make Sean Hannity proud. Asked about the child separations, and whether she agreed with Ward's assessment that the practice was "humane," Sinema says, "No, I opposed it when Obama suggested it, and I oppose it now."

That approach is not without risk in a party that thirsts for Trump bashing. "I have some serious questions," Steven Slugocki, Democratic chairman in Maricopa County, told The Associated Press. "That's not to say I won't support her. The alternative is far worse."

For now, it seems to be paying off. A late June CBS poll found Sinema easily beating all three of her potential Republican challengers. But analysts say Democrats shouldn't take anything for granted. Between 11 and 27 percent of voters in the survey said they were undecided, planned to vote for a third party or won't vote in November. As FiveThirtyEight notes, a disproportionate share of these voters are Republican, and they'll likely come off the fence closer to Election Day, once sour feelings from the contentious primary have subsided. With polls showing her leading the GOP field, McSally hopes she'll be the beneficiary.

'Pry It Out of My Cold, Dead Hands'

McSally will tell campaign crowds about how she has attended exclusive White House movie screenings and takes calls from the president and his staff. In well-heeled Scottsdale, she told the Palo Verde Republican Women club recently how she met Trump during a health care conference and told him about the "big-ass" Warthog jet she once flew. The punch line, of course, involves dumping on Obama. "I said, 'The last administration tried to put it in the boneyard, but you're going to have to pry it out of my cold, dead hands, Mr. President.'" The audience applauded loudly, according to reporters.

That kind of camaraderie was unimaginable just two years ago.

When the infamous Access Hollywood tape came out before the 2016 election, McSally tweeted: "Trump's comments are disgusting. Joking about sexual assault is unacceptable. I'm appalled." She also said she "utterly disagreed" with his campaign threats to withdraw from NATO unless other countries began paying more for defense, and she even cast some shade on his political style, remarking that "hopefully" Americans can have "a battle of ideas of public policy solutions for complex problems, as opposed to a WWF tournament." She has refused to say whether she voted for him in 2016.

A month after Trump's inauguration, McSally held a town hall meeting in southeastern Arizona, where she criticized the new administration and reiterated her opposition to the border wall. "Some of their decisions and the way they have implemented them have certainly not been well coordinated, not well implemented," she said of the travel ban targeting Muslims. "I'm concerned about not shifting from campaigning to governing." Asked whether she supported Trump's wall proposal, she said, "Not a continuous, 2,000-mile border wall, no."

Republican rivals—and even supporters—say McSally isn't just evolving; she is hitting the erase button wherever possible. Democrats and some Arizona political columnists call her "McShifty." "None of us can count on Martha keeping a campaign promise, as she will fall for whatever the D.C. elite tells her to do at the time," says Representative Paul Gosar, a conservative House Freedom Caucus member who has endorsed Ward. "I have seen that firsthand."

Echoing the other candidates, McSally is now using the opioid crisis (Arizona saw a 74 percent increase in opioid deaths between 2012 and 2016) to claim that a border wall will deter heroin smugglers bringing narcotics across the southern border. That claim follows the one Trump made in his last State of the Union address. While it is true that most of the heroin in the U.S. comes over the Mexican border, the more prevalent and deadly narcotic Fentanyl is coming from China and often through the U.S. Postal Service.

To the border hawks, though, McSally is weak. In Congress, she has co-sponsored bills to help recipients of DACA. But in January, after she decided to go for Flake's seat, she tried a new tack, downplaying immigration as an issue while blaming Democrats for keeping it on the boil. She blasted her colleagues across the aisle for "dicking around" on immigration, telling Fox News that their DACA demands amounted to "trying to come up with some issue that's not even a top-20 priority of the American people."

Today, she says any aid to Dreamers must be tied to money for border security. "I have also consistently shown—with my votes, words and actions—that I am willing to support a legislative solution for the DACA population," she wrote in an editorial for USA Today. "But any solution must be combined with fixing the root causes of why we have a DACA population in the first place. We can't incentivize more illegal immigration and find ourselves in the same situation in the future."

Arizona's Republican Party is a big tent, and as diverse as any state party in America, perhaps more so, with its large share of right-leaning but officially non-aligned voters. Among the geriatrics and growing population of Hispanics of Maricopa County, the millennials of Tempe and Tucson, and the unpredictable independents of the flatlands, Arizona holds in microcosm the demographic past and the fractious future of the GOP in America. Can they all be corralled with Trump's red meat?

For now, the Republican position is, yes, they can. When The Washington Post recently asked her about her "visible shift to the right on immigration," McSally could have denied it or even explained how her position has evolved. Instead, she snapped back with a phrase from her party's new standard-bearer: "Fake news."

Correction: An earlier version of this story said Kyrsten Sinema was a self-described atheist. She calls herself unaffiliated with any religion.