Three decades into the rule of Prime Minister Hun Sen, Cambodians went to the polls on Sunday to give the strongman ruler another five-year term.

It wasn't hard to do that: His cronies had forced the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), the main opposition, into dissolution last year.

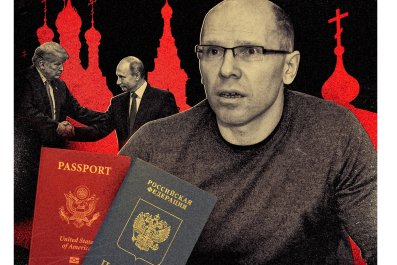

Hun Sen and his backers tried to convince the public of their legitimacy. But observers say the outcome was predetermined, thanks in part to the interests of his biggest supporter: China.

Under Hun Sen's rule, billions of dollars in Chinese investments helped Cambodia become one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. The financial influx is part of an aggressive Chinese strategy to win influence in Cambodia after its years on a rocky, U.S.-backed path. By 2017, China had become Cambodia's largest trading partner, with total trade volume reaching $5.8 billion, up 22 percent from 2016.

"In this pivot towards China, Hun Sen has explicitly come out and said to the West, 'I don't need your money anymore,'" says Alice Harrison, a senior campaigner with human rights group Global Witness, which composed a detailed report of the ruling elite and its vast connections to Beijing. "The economy has gotten to the point with so much Chinese financing that he feels very safe in their hands."

But few of those benefits trickle down to ordinary Cambodians. "In a large number of cases, the benefits have been minimal or negative," says Sebastian Strangio, author of Hun Sen's Cambodia. "Chinese state companies usually bring in their own labor force to build infrastructure like roads, dams and bridges. And villagers have lost their land to dam and real estate projects."

Despite a burgeoning economy, household debt among Cambodia's population (15 million at the end of 2017) has grown to an all-time high of $2.8 billion, according to the National Bank of Cambodia. Yet Hun Sen works to return China's favors and applaud its help. "I would like to highly evaluate the Chinese government on the respect of our independence, sovereignty and various measures implemented by [Cambodia] in order to protect social security and stability," he said during a July 2 speech.

In 2016, Hun Sen blocked the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) from unilaterally condemning China over its territorial claims in the South China Sea dispute. He has also repeatedly come to the defense of large-scale Chinese projects, despite widespread criticism that they create a closed economic loop that leaves behind environmental damage, along with little benefit to Cambodians.

Such support makes sense given Hun Sen's gradual move away from the illusion of democracy that the U.N. helped establish in Cambodia's first post-genocide elections, in 1993. As his grip on the country has increased, so has Chinese investment.

The consolidation of power occurred after Hun Sen nearly lost the 2013 elections, which were accompanied by widespread violent protests over allegations of election fraud. He forced the closure of democratic institutions that had been in place for nearly three decades, including the U.S.-funded ASEAN and Radio Free Asia. Last year, he imprisoned CNRP leader Kem Sokha on trumped-up treason charges, while a Supreme Court loyal to Hun Sen dissolved the CNRP entirely, forcing its remaining leadership into exile.

The moves mark what opposition activists say is the demise of democracy in Cambodia. "It is dead in this election and is totally a sham," says CNRP Deputy President Mu Sochua. "Hun Sen will not be a legitimate leader in the next government."

On July 27, Hun Sen and his Cambodian People's Party (CPP) entertained tens of thousands of supporters in white shirts and hats, who waved flags and chanted as they rode on trucks into the capital city of Phnom Penh for his mass rally. During his speech, Hun Sen branded CNRP's members as traitors and defended its dissolution as a necessary means to maintain the country's stability.

"If we didn't eliminate them with an iron fist, maybe by now Cambodia would be in a situation of war," he said. "No peace, no development. Voting for the CPP will guarantee the peace."

After the crackdown, the U.S. pulled financial support for the upcoming elections. The European Union is reconsidering a vital duty-free trade program for Cambodian imports, but China is filling the void, reportedly giving the National Election Committee $20 million for equipment, including polling booths, laptops and computers.

China also wants to avoid the possibility of a new regime undermining its investments, as happened in Malaysia, where Mahathir Mohamad, elected prime minister this past spring, is now re-evaluating billions of dollars in Chinese projects cleared by the former government. "[China] just wants to make sure whoever wins will continue the same relationship with them, with the same trajectory," says Ou Virak, director of the local think tank Future Forum.

The setback redoubled Chinese efforts to ensure Hun Sen's victory. In July, U.S. security-research company FireEye announced that it had found evidence of a Chinese hacking team infiltrating computer systems belonging to Cambodia's National Election Committee, opposition leaders and the media. Amid the accusations, Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia Xiong Bo has attempted to divert attention by criticizing the European Union for interfering in the elections by threatening Cambodia's participation in the EU's tax-free Everything But Arms trade initiative.

"No matter what the EU decides to do," Xiong said on July 23, "China will continue to expand and deepen our cooperation with Cambodia in all fields, especially in terms of trade and economic relations."

For some experts, China's unparalleled level of involvement in Cambodia's elections is an indication of things to come, as the former's growing investment in other regional countries—part of the mammoth Eurasian One Belt, One Road initiative—hits record levels.

"It's certainly unprecedented in a way, but the backtracking of democracy is not just happening in Cambodia," says the Future Forum's Ou Virak. "The one common denominator [in Asia] is China."