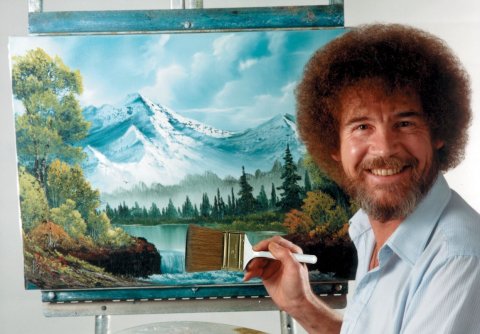

Craig Richard could not stop watching Bob Ross paint.

It was 1983, and Ross's television show, The Joy of Painting, had recently premiered on PBS. Richard, then in his early teens, would come home from school in Massachusetts, flip on the TV, and settle in as the painter brought clouds, mountains and "happy little trees" to life on a blank canvas.

Ross famously narrated his creative process in a voice that topped out at a pleasant murmur. "There was something hypnotic about his voice," Richard recalls. "I would put a pillow down on the floor and end up falling asleep halfway through one of his paintings. I don't think I ever saw him finish one."

During viewings, Richard often felt a euphoric, tingly sensation in his head and upper body. "My brain would quickly feel fuzzy, and my whole body would relax," he says. It reminded him of the inexplicably relaxing pleasure he felt overhearing his younger sister learning to read. "When she would sound out the words and read in that gentle, little-child voice, I would fall asleep."

It would be 30 years before Richard learned this sensation had a name. He grew up, earned a Ph.D. and became a professor of biopharmaceutical sciences at Shenandoah University in Virginia. Then, around 2013, he was listening to a podcast when the hosts began explaining something called "ASMR." Richard was bewildered. People who experienced it, Richard recalls them explaining, "tended to really like Bob Ross. It caused them to have head tingles. I was like, Oh!"

Widely enjoyed but little understood, ASMR, short for autonomous sensory meridian response, refers to this euphoric feeling, which can be experienced in a variety of ways; ASMR "triggers" can be aural, touch-based or both. "For me, soft, soothing sounds such as pages being turned, or someone writing on paper with a pencil or any gentle rustling sounds elicit a response," says Karen Schweiger, who runs an integrative healing touch therapy practice in New Jersey. The sensation frequently arises from situations in which a person is receiving close, gentle attention. "Having my hair washed or brushed," says Schweiger, "the feeling of a makeup brush moving over my face and the sound of a cat purring against me are just a few."

ASMR mania has flourished in internet communities and whisper-themed YouTube channels since roughly 2010, when the term was coined by a health care manager named Jennifer Allen, who founded the first ASMR-themed Facebook group. Now, as scientists begin to probe its bewildering mysteries, Richard is emerging as its most devoted chronicler in the academic world. In 2014, he launched the ASMR Research Project, which has surveyed more than 20,000 individuals about their experiences with it, as well as the website ASMRUniversity.com, which obsessively tracks related research.

His new book, Brain Tingles, doubles as a brief history of the phenomenon and the first book-length how-to guide for provoking ASMR in others. The endless taxonomy of trigger suggestions includes: Roleplay as somebody administering a cranial nerve exam! Make scratching noises with fabric swatches! Explain the iOS settings on an Apple mobile device! At times, this feels like an instruction manual teaching you how to be boring, which makes sense: Excitement is anathema to the ASMR experience.

If the book's prescriptions seem odd, its timing is perfect. ASMR is everywhere lately, bursting from the internet's fringes and exploding into mainstream view. There are now more than 13 million ASMR videos on YouTube, with some of the creators (like "Heather Feather" and "Cosmic Tingles") becoming celebrities in their own niche universe. Major brands like Ikea have created ASMR-influenced commercials; in May, Applebee's released a 60-minute video of meat sizzling. (Not great for inducing the tingles, Richard says—though "instead of people yelling at you to eat their burgers, it's nice to tune into a commercial that is relaxed.") In 2017, Battle of the Sexes became the first Hollywood film to contain a scene designed to induce the sensation. W Magazine even persuaded actors Salma Hayek and Jake Gyllenhaal to record their own whisper videos, replete with frequent props like paintbrushes and bubble wrap.

In June, the comedian Brandon Wardell released the world's first ASMR-themed comedy album (available on Spotify). Every joke is whispered. "I love getting high and then watching ASMR," Wardell tells Newsweek. "I'm all the way kushed out, and then I watch these ASMR videos and I'm cross-faded on kush and ASMR."

Most significantly, there is now a small body of research aimed at figuring out what ASMR is and how it might be useful. In June, researchers from the University of Sheffield and Manchester Metropolitan University published the first study to demonstrate the experience's physiological effects, including a reduced heart rate. "Our research studies consistently show that ASMR is a relaxing, calming sensation that increases feelings of social connectedness," Giulia Poerio, one of the co-authors, told Newsweek that month. The results are a boon to researchers who believe ASMR triggers could eventually be prescribed for people fighting anxiety or sleeplessness.

Craig Richard is strangely well-suited to being the unofficial mastermind of ASMR knowledge. The 48-year-old speaks in a gentle and reassuring manner, much like Bob Ross (minus the nimbus of hair—Richard is bald). Whether this is a born gift or a side effect of studying ASMR videos for five years, that's uncertain.

When the science professor first learned what ASMR was, he thought, "OK. It's a physiological reaction. I'm a physiologist. I can't wait to read about all the science being done on this." And then he searched online. Nothing. "There weren't any publications. No peer-reviewed research studies." He soon got to work.

Richard can attach a date to the first known attempt to define the response: October 29, 2007. That's when a member of the online health forum SteadyHealth.com began a discussion thread with the title "Weird sensation feels good." Hundreds of replies rolled in. Some users proposed the phrase "head orgasm."

As it turned out, many of them had been turned on by Ross. "I'd watch the shows over and over," says Schweiger. "Listening to his voice, watching him paint, hearing the sound of the brush on the canvas was remarkably calming. Anxiety has been prevalent in my life for as long as I can remember, so finding this escape was a godsend."

Ross, who died in 1995, has found a remarkable afterlife as ASMR sage. "He's sort of the godfather of ASMR," says Joan Kowalski, the president of Bob Ross Inc. "People were into him for ASMR reasons before there even was an ASMR." The painter knew—and never minded—that his program put viewers to sleep, she insists. "People would tell him, 'I don't want to hurt your feelings, but I never make it through your show. I'm out 10 minutes in.' He played into it once he realized it was a thing."

Decades later, we've got a rudimentary sense of why Ross's show was so popular. The first thing to know about ASMR is that it can be intensely pleasurable. The second is that, despite terminology like "brain orgasm," it is not a sexual experience—well, not inherently sexual. Like anything online, it can be sexualized if you're into that sort of thing, says Richard. (Remember the famous axiom—or "Rule 34"—of the internet: "If it exists, there is internet porn of it.")

"There is a genre of ASMR called ASMR erotica," says Melinda Lauw, the co-founder of an immersive "ASMR spa" called Whisperlodge. "If you Google that, you'll find lots of sexy whisper-ASMR videos. If you go on any porn site and search 'ASMR,' you'll find lots of ASMR videos there, too." While Lauw doesn't judge anyone who finds sexual gratification in such content, "I feel like the focus should still be on how it can help us relax rather than help us get aroused."

Precisely why ASMR calms people remains unknown. Richard, whose special training is in reproductive sciences, has theories. In his book, he suggests that ASMR may have a biological basis. He came upon this idea as he was watching one of his favorite stars of the genre, "Gentle Whispering," a.k.a Maria (who goes by only her first name for safety reasons). She reminded him of the way mothers talk to an infant they want to soothe. "It's very maternal," Richard says. "Maybe these videos are tapping into something we're hardwired to respond to from birth. When someone talks to us softly, when someone touches us gently or looks at us in a caring way, our brains are wired to know that this person is here to help us. And now we can relax, because we feel safe."

There has been no conclusive research that confirms this conjecture, though it would explain why, Ross aside, the majority of ASMR videos on YouTube seem to feature women whispering. Richard was intrigued by a 2012 BuzzFeed article, which floated the idea of a connection between ASMR and the intense pleasure primates experience when grooming each other. It's possible—though unproven—that the physiological effects are similar, such as an increase of oxytocin (sometimes called the "love hormone") and endorphins in the brain.

When he interviewed Amanda Dettmer, a primate neuroscientist who studies the mother-infant bond in rhesus monkeys, she saw parallels too. "I have seen more monkeys than I can count turn into 'limp noodles' while being groomed, and most fall asleep for some period of time," she told Richard. "[But] we'll never be able to have a monkey tell us if it feels that tingly sensation in its head."

ASMR, like many responses and emotions, seems to occur on a spectrum. For some, the sound of whispering or soft rustling is like nails on a chalkboard, producing tension rather than calm. There is no clear reason for this, mostly because "we don't even know how to test it yet," Richard says. His ballpark guess would be that ASMR triggers a somewhat relaxed response in about 40 percent of the population, with 20 percent experiencing the more euphoric "staticky brain tingles."

"Future research will probably focus on establishing objective ASMR tests," says Agnieszka Janik McErlean, a psychology lecturer at Bath Spa University in Britain. In 2017, she published a paper on variations in people's responses to ASMR. Among her conclusions: People who experience ASMR have a similar personality profile to those who experience synesthesia (a perceptual phenomenon in which some people associate sounds or numbers, for instance, with specific colors). "I imagine," she adds, "that we will see research systematically investigating ASMR's potential therapeutic effects."

Kowalski has already heard from a doctor or two who already prescribe Ross videos to their patients. "I imagine them writing the little prescription sheets," she says with a laugh. In the meantime, plenty of people are self-medicating.

Schweiger describes her company, In Your Arms LLC, as "a holistic integrative healing touch therapy practice including therapeutic cuddling sessions and meditative nature walks." She was encouraged when a client recently asked her to use ASMR in a cuddling session, and she plans to incorporate touch-mediated ASMR sessions into her regular practice this fall.

Ally Maque, a 28-year-old ASMR YouTuber who goes by "ASMRrequests," has nearly 500,000 subscribers and now makes a full-time living from her whisper videos. (A recent "unboxing" video, for instance, is sponsored by FabFitFun.) Maque has received messages from victims of trauma, "even veterans who have come back from tours overseas, who say my videos provide comfort or help them sleep when they haven't been able to for weeks."

In one instance, Maque heard from the parents of a young boy who suffered from crippling migraines. "They said that a series of videos I did, where I read fairy tales from a bedtime story book—whenever they'd put those videos on for their child when he was suffering, it would help," Maque recalls. "That one brought me to tears."

"My initial feeling was that ASMR would be a super niche community," says Lauw. "But it seems to be growing really quickly. There's so much potential for ASMR to become a bigger thing, like meditation."

A stranger is in my apartment tickling my face with a makeup brush.

She speaks only in whispers, gently narrating which triggers she is using. Ambient music drifts over from my desk. By the time she begins to massage my scalp with a device that vaguely resembles a squid, I'm floating in the clouds.

The stranger's name is Chia Lynn Kwa, and she works for Whisperlodge, which Lauw co-founded with playwright Andrew Hoepfner. The company calls itself an "intimately-sized immersive theatre performance," though its focus is inducing ASMR rather than Shakespearean tragedy. The typical Whisperlodge event—a "narrative symphony" of trigger sounds—takes place for small groups of 10 or fewer (limited, so far, to New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles). But it also provides the premium service, "Whispers on Demand," in which tingles are delivered in a one-on-one setting. The hour costs $100, about the same as a good massage, and, for me at least, the experience is equally stress-relieving. (Of course, I do experience ASMR and have since childhood.)

Whisperlodge is perhaps the most inventive business venture to emerge from the ASMR boom. Lauw, a 26-year-old Singaporean artist and curator, obsessively watched odd YouTube videos during her teens without understanding why. "I was watching a lot of instructional massage videos," she says. "That led me to many other accidental ASMR videos."

Living in a strict household with a firm emphasis on schoolwork, Lauw found herself watching in secret, to relax. "I was embarrassed that I was watching all these massage videos," she says. Then she saw a YouTube comment to the effect of, If you like this, you need to Google "ASMR." "When I found out that there was a community and other people felt the same, I felt: 'Oh my god, I'm not this super-weird person.'"

In college, she studied visual art and wrote her thesis on ASMR. "I found it really difficult to track the history of it," she says. Richard "is the one who's been archiving everything."

One day she saw an immersive theater performance and became captivated. She was subsequently introduced to Hoepfner, an immersive theater nerd who knew nothing about ASMR but had created a show called Houseworld that inadvertently induced ASMR in some viewers. Together, they launched Whisperlodge in 2016.

Prior to the session, "Whispers on Demand" requires that I sign a waiver affirming that I will remain clothed and "all whispering and touching…will be conducted in a professional and non-sexual manner." (I'm reminded, too, that the session is "not a substitute for medical care.")

Kwa, friendly but quiet-mannered (essential characteristics for this job), arrives with a little pouch that serves as her ASMR toolbox. On a small table beside my couch, she places some of the supplies, including a comb, a makeup brush and the squid massager, which is like the Chekhov's gun of an ASMR session; as soon as I spot it, I am waiting for it to come into play.

Before she begins, Kwa encourages me not to be self-conscious about bodily sounds that may occur, like burping or stomach growling. She tells me to relax. And then, as soon as the Brian Eno ambient composition and whispering begin, the molecular structure of the room seems to change. The initial awkwardness dissipates: I feel tingly but also… safe? Kwa shows me a tiny bottle of tea tree oil and sprays a drop on my wrists. She gently crinkles newsprint and crepe paper near my face.

The tingles are light but grow stronger as Kwa moves on to tactile triggers, which affect me the most. The gentle touch of the makeup brush is thrillingly nice; the comb across my scalp brings a fuzzy euphoria. At its best, ASMR offers a quiet little refuge from the roaring world outside. If this is how primates feel when getting groomed, then let me be reincarnated as a monkey. Eventually, Kwa's voice emerges from the ether. "We're almost at the end of our session. Would you like a refreshing spray of rosemary mist?" Yes. Yes, I would.