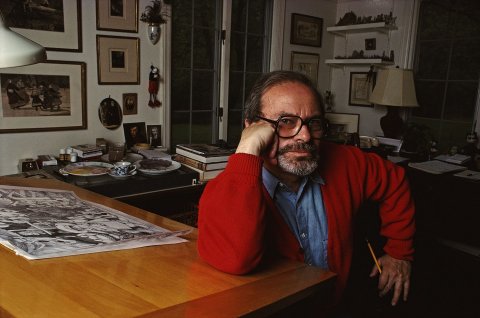

Arthur Yorinks first met Maurice Sendak in 1970, when Yorinks was 17 and Sendak was 42. "I read an article about him in The New York Times and thought, If I meet this guy, it will help me move out of my parents' house," says Yorinks. "It made no sense, but I was determined."

By this point, Sendak was already a celebrated children's author, thanks to 1963's Where the Wild Things Are (which became a 2009 Oscar-nominated film by Spike Jonze). Yorinks aspired to write short fiction, though he would later go on to write the 1986 Caldecott Medal-winning children's book, Hey Al.

Yorinks remembers their first phone conversation vividly: "Toward the end, Maurice asked me what I thought of Winnie-the-Pooh. I blurted out, 'Oh, I hate that book'—which I do," Yorinks says with a laugh. "There was a pause. I thought, Oh God, I'm an idiot. Then he pipes up with, 'Why don't you come for lunch next Tuesday?'"

Thus began a beautiful friendship, which included collaborations like The Night Kitchen Theater and Sendak's only pop-up book, Mommy?. They eventually became Connecticut neighbors when Yorinks unknowingly moved next door, earning a nickname that would later title their book. "I get in the car to get lunch with Maurice, and in three minutes I'm in his driveway," Yorinks laughs. "He comes out and yells, 'Presto!' I didn't want to let him get away with sticking a name on me, so I said, 'If I'm Presto, you're Zesto.'"

The pair were well suited, sharing a dry wit and melancholy moods. (In Jonze's 2009 documentary about Sendak, the author confesses to a "permanent dissatisfaction.") In their near-daily walks around the older man's estate, says Yorinks, they lamented the publishing industry ("moronic and corporate"), the state of the world ("God only knows what Maurice would have thought now!") and their favorite topic: cake. "In the early days, you had to bring Maurice a cake when you visited," Yorinks says. "He was obsessed with this New York bakery, Sutter's—the best chocolate layer cake I've ever had. When Sutter's closed, it was the end of cake."

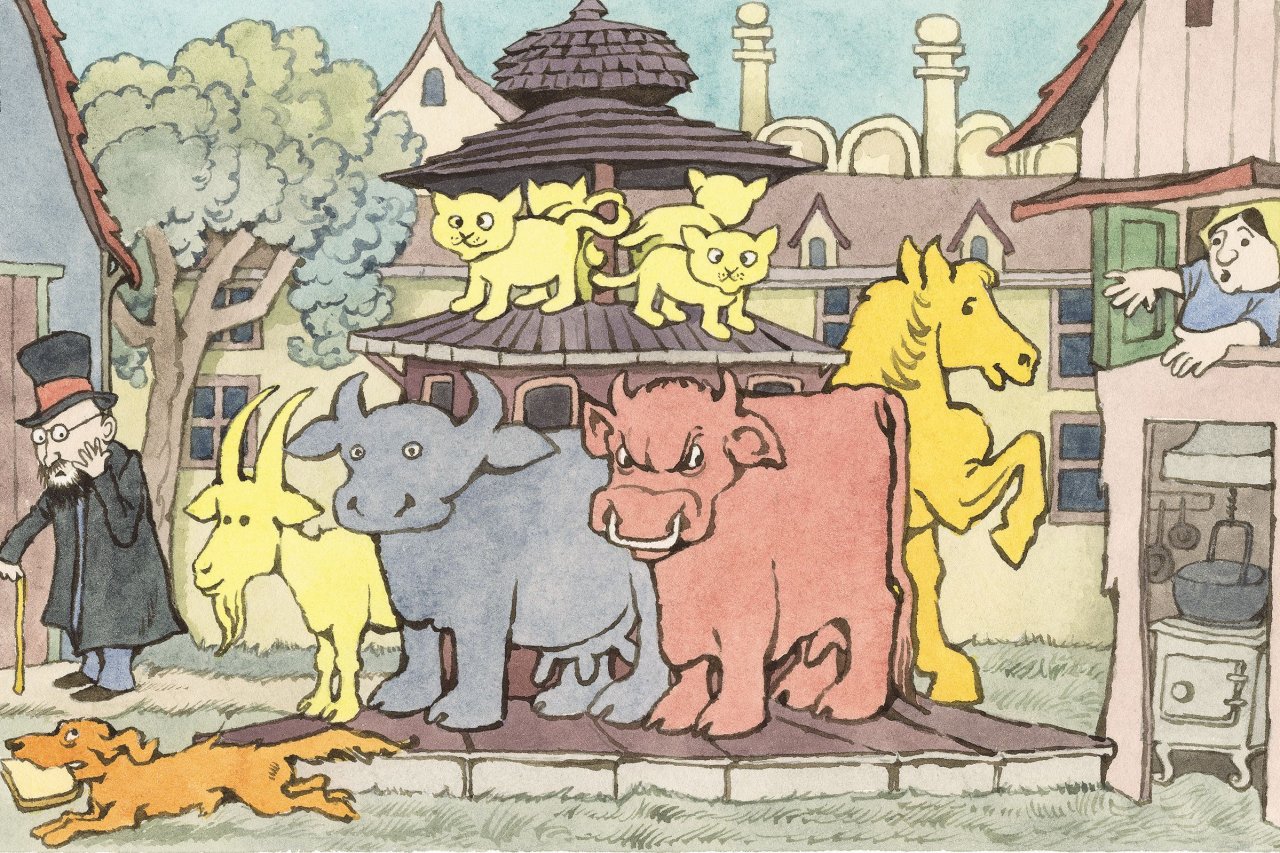

Those themes found their way into Presto and Zesto in Limboland (out September 4), which came about one afternoon in Sendak's studio, nearly twenty years ago. Yorinks, now 65, remembers it fondly. "We were two short jazz musicians, two storytellers improvising off of each other," he writes in the Presto afterword. They were riffing off 10 illustrations Sendak had created a decade earlier for two performances of Czech composer Leoš Janáček's Říkadla by the London Symphony Orchestra. Each bizarre and colorful drawing was based on a nursery rhyme, all were unrelated. To only be used for two performances seemed a waste to Yorinks. He said to Sendak, Why not make the pictures into a book?

"It was really a way of wasting an afternoon, not often done by Maurice," Yorinks says. They spun an absurd tale of two best friends, Presto and Zesto, who get caught in a strange land where they encounter goats, a pants-destroying monster and a tragic lack of cake. In the end, like so many of Sendak's books, the friends return home safely (having eaten cake). The authors spent months fine-tuning that brainstorm into a manuscript, intending to publish it one day.

Life got in the way for both men, and the story was put in a drawer—until Lynn Caponera, Sendak's caretaker, now president of the Maurice Sendak Foundation, found the manuscript in 2016. She sent it to Sendak and Yorink's longtime editor, Michael di Capua.

"I had no idea Arthur and Maurice were working on anything. If I had, I probably would have said, 'Where is that manuscript?!'" says di Capua with a laugh. "When I read it, I felt faint with joy."

Yorinks feels similarily. "It's his last book. There are no other lost manuscripts." (Previously, Sendak's last book was 2013's My Brother's Book, published eight months after his death.)

Sendak died of complications from a stroke in May 2012, at the age of 83. Yorinks, who had since moved back to New York, heard the news through a friend of his wife. "We had talked several years before that," he says heavily. "It wasn't an extraordinary last conversation, or a bad conversation, it was just an ordinary conversation. But that's why this book is such a miracle. It is an epilogue to a 40-year-old friendship."