In 1976, when movie audiences watched Paddy Chayefsky's dark comedy Network, they laughed. When English playwright Lee Hall re-watched the film in 2008, he cringed. "What Paddy predicted as mad satire in 1976 is documentary realism in our age," he tells Newsweek. "Week by week it becomes more relevant."

Chayefsky, who won an Oscar for his screenplay and died in 1981, was already noting the diminishing distinctions between TV news and entertainment, and the ominous ability of the medium to harness popular rage. Hall, best known for the 2000 screenplay for Billy Elliot as well as its Tony-winning musical adaption, recognized not only Chayefsky's eerie prescience, but also "a very robust piece of dramatic literature—in the same tradition as Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams.

"My job," Hall adds, "was to do keyhole surgery and usher the story into a new format without doing too much damage to an already brilliant script."

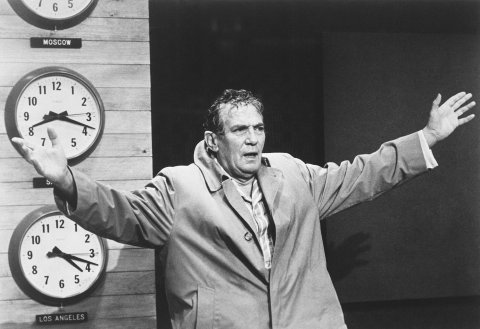

It would be hard to improve upon. The screenplay was voted the eighth greatest in the history of cinema (by the Writers Guild of America in 2005), and the film—directed with scathing precision by Sidney Lumet—ranked 64th in the American Film Institute's 100 greatest American films in 2007. The story centers on Howard Beale, an aging, alcoholic newscaster (played by Peter Finch, who died shortly after production, winning a posthumous Oscar for the role). After he's fired from the fictional UBS network, he announces he plans to kill himself on his final broadcast—attracting record numbers of viewers to the ratings-challenged network. Rather than send him to therapy, a cutthroat executive, Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), offers Beale his own show. And thus is born his mantra, for which Network is famous: "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!"

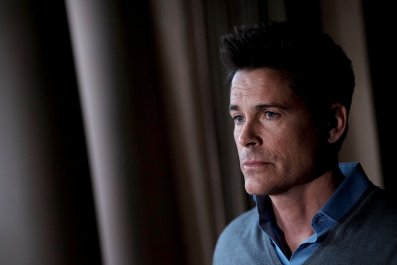

The stage adaption of Network, which debuted at London's National Theater last year, begins its 18-week Broadway run on December 6 at New York's Belasco Theatre. Breaking Bad's Bryan Cranston returns as Beale (following rave reviews and an Olivier Award); Tatiana Maslany, the Emmy-winning star of Orphan Black, makes her Broadway debut as Christensen. Ivo van Hove directs, heightening the anxiety and claustrophobia of the 24/7 news cycle with the packed set—a frenetic newsroom—and the camera crew that circles Beale, like vultures, projecting every second of his meltdowns on a 20-foot screen.

But if you are expecting an update, accessorized with social media and crowds of MAGA-hatted, mad-as-hell Trump fans, you'll be disappointed. The play remains in the 1970s. "We wanted to allow the audience to make their own connections," says Hall. "It didn't need to be about Twitter and mobile phones because the problems of 1976 are the same problems we have today: the network of capitalism and globalization."

That said, you'll need the salary of a corporate executive to pay for the $399 seats that van Hove has placed on the stage (the price comes with dinner and drinks). The director had onstage seating for his Tony-winning production of A View From the Bridge as well, but in this case, the gesture is intended as a commentary on the complicit role of the watcher. "As a playwright, I was kind of horrified when I heard this might happen, but Ivo said, 'Trust me,' and he's completely right," says Hall. "He's found a beautiful metaphor for how we watch. It's interesting to see somebody sitting on a seat, having a meal, watching a projection of Cranston, rather than watching the real Cranston, who's standing right in front of them."

Even the world events included in Chayefsky's script were oddly prophetic. "For example," says Hall, "I've just come out of rehearsal where we're working on a speech, where, in 1976, [the characters are] talking about the Saudis and Saudi money. We had [that speech] in London, but I had considered changing it to something more relevant for the Broadway run. I hadn't gotten around to it, and then…I mean…have you read the news? Now people will probably think I put that in!"

For the most part, changes were structural. In the film's second half, the focus shifts from Beale to his friend and boss, Max Schumacher (William Holden). Hall felt that was "a strange move, dramatically, especially for theater."

By keeping the focus on Beale, Hall also mitigates the film's misogyny. Thanks to Dunaway, who won an Academy Award for her performance—one that swings stylishly between sensuality and absurdity—you can't help but love Christensen even as you hate what she stands for. But this was 1976, and strong women still had to get their comeuppance. (Lumet reportedly told Dunaway that he would edit out any attempts to make her character more sympathetic or vulnerable.) In the end, she's put in her place by the honorable Schumacher—after he ditches his wife and kids to sleep with her. Schumacher ultimately dismisses Christensen as part of the generation that "learned life from Bugs Bunny."

"Watching the film, in retrospect, it feels different, to see this very powerful, creative young women questioning the complacency of a generation of men who had it easy," says Hall. "Tatiana [Maslany] as Diana embraces that."

"I don't think her intentions are bad," says Maslany of Christensen. "She just deeply wants something, and she's unapologetic about it." The actor has not reached out to Dunaway to discuss the part ("I don't exactly have Faye Dunaway on speed dial—that would be nuts!"), looking instead to "find my own way."

If the film has a flaw it's Schumacher's oddly sincere love for Christensen, a weakness film reviewers noted in 1976. "I don't know what he expects of her," says Maslany. "I'd love to know that!" Eventually, Schumacher confronts her, and "what I love about that moment," says Maslany, "is that Diana fails to uphold what she's expected to be. She doesn't say, 'Love me despite all my shit.' She says, 'I can't love you. I don't know how to do that.' It's the opposite of what we expect of a woman on screen."

There is, of course, the irony now of Schumacher (played by Tony Goldwyn on Broadway) chiding "the television generation" at a time when Facebook algorithms have journalists feeling nostalgic about CNN—a point not lost on Hall. "The cable television era was something to be horrified by in the '70s," he says. "But as we're finding with social media, the problem is not the technology, it's the corporate structure underneath."

At one point in the show, surrounding characters describe Beale as an "angry prophet, denouncing the hypocrisy of our times" and "a manifestly irresponsible man on TV." Hall hopes the audience won't leap to obvious conclusions. "Beale isn't Trump," he says, "He's an ordinary man who falls into the trap of anger and is manipulated by the very forces that have provoked his anger in the first place. We all feel like Howard Beale, but therein lies the trap, because how we feel—angry—is not a solution. In the end, Howard exploits himself. That's the real story of Network."

Still, Hall does tack on a final moment that is squarely aimed at our times. The film's Beale never learns the limits of anger; he's murdered on camera after publicly criticizing USB's sponsors. On Broadway, he gets a posthumous rejoinder: "The real truth, the thing we must be afraid of, is the destructive power of absolute beliefs."

Network debuts on December 6 and runs through March 17 at New York's Belasco Theater.