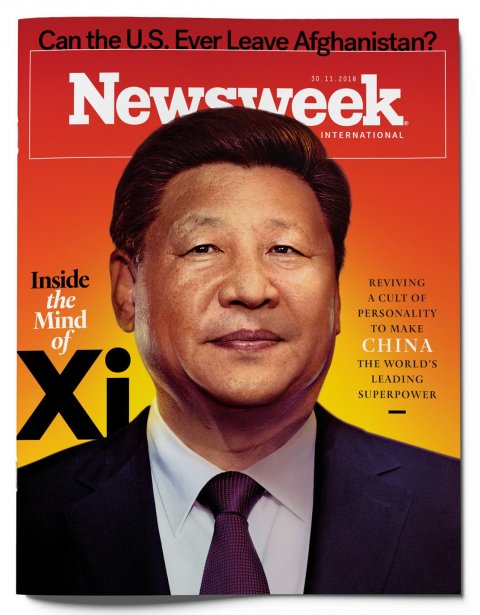

In early October, Vice President Mike Pence gave a speech in Washington, D.C., that, to many foreign policy analysts, signaled nothing less than the formal onset of a 21st-century cold war. This time, China, a single-party dictatorship and the world's second-largest economy, is cast as the United States' overarching adversary. Now, President Donald Trump is set to sit down with the man who leads China, Xi Jinping, at the G-20 summit in December, in what may be a last effort to avoid a potentially ruinous trade war.

But who is Xi, what does he believe and how does he govern? French journalist François Bougon set out to answer these questions in a new book, Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping. As a former Beijing correspondent for Agence France-Presse, he watched Xi, the son of a revolutionary pioneer, rise through the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party to become such a towering figure that his name is already inscribed in its constitution—"a privilege," Bougon writes, "that only Mao Zedong, founder of the Party, has previously enjoyed in his lifetime."

As U.S. relations with Beijing sink to their lowest level since just after the massacre at Tiananmen Square in 1989, understanding Xi, the man who runs the most populous nation on Earth, is arguably more important than ever. —Bill Powell

In 2009, there was a rare moment of truth. Xi Jinping was in Mexico, the "backyard" of China's great American rival, shoring up his international standing with multiple trips abroad. It was February, and Xi was still only vice president, but already one of the favorites for the leadership. Standing confidently behind the microphone in front of the Chinese Embassy in Mexico, he faced a specially selected audience of compatriots—expats, diplomats, businessmen and students. The theme of the event was global cooperation, and the peaceful atmosphere made his remarks all the more striking.

"There are certain well-fed foreigners who have nothing better to do than point the finger," he declared. "Yet, firstly, China is not exporting revolution. Secondly, we are not the ones exporting poverty or famine either. Thirdly, we do not cause problems in other people's countries. What more can I say?"

The target—the one who supposedly did export famine and unrest—was clear, as the deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico pointed out in a diplomatic telegram. He described Xi's "unusual behavior" at the start of his visit "to a country with strong ties to the United States" as drawing a line in the sand.

China is particularly resentful of being an object for Western criticism when it deems its American rival to be a much more questionable superpower. Xi's declaration was manifesting real annoyance. When abroad, he generally focuses on win-win agreements and the rise of his country. His comment revealed not only his national pride but also that China, now endowed with a strong economy and army, no longer needed lessons from anyone. Beware, it said; China has become touchy.

Well-studied modesty in the nation had given way to nationalism in the 1990s, a shift best described by the title and substance of the best-selling 1996 book China Can Say No. Written by five young Chinese intellectuals, it accused the United States of hindering China's growth and wanting to contain it, as the U.S. had done with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

In 2009, some of these authors struck again with another work, Unhappy China, asserting that the country must adopt a hegemonic position in the world from which to oppose Western influence. The time had come to take a leading international role. Far from pulling back, what was needed was an expansion of influence.

Xi rode that surge of national pride. He came to power in 2012, flattering young nationalists with one hand and, with the other, reaching out to the proponents of 1980s neo-authoritarianism, who were persuaded that only a strong regime had been able to save the country after the repression of the Tiananmen movement. Gone were the days when, following the 1989 massacre, China had been marginalized by other nations, when then-leader Deng Xiaoping advised "keeping a low profile and biding our time."

Xi has broken with this low-profile doctrine, even if this means reviving an old enmity with Japan. And even if it involves explicitly identifying the United States as the great 21st-century enemy, determined to weaken China.

To further his foreign policy agenda, Xi has gone even further than his predecessors in his approach to the military. In 2016, he suddenly gave himself a new title, that of commander in chief. He is now in charge of everyday military operations in case of external conflicts or regional tensions.

In the South China Sea, he ordered the building of artificial islands to manifest Chinese presence in territories over which neighboring countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines claim sovereignty. With this move, Beijing has, for the first time, flouted a ruling of the intergovernmental Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. In the summer of 2016, following an appeal from Manila, the court concluded that Beijing had "violated the Philippines's sovereign rights." Xi rejected the ruling. The Xinhua state news agency was even more explicit, denouncing a Western plot to contain China's development.

Xi's line of attack—or, from his viewpoint, his means of establishing himself—has included making the most of Western countries' weakness after the financial crisis of 2008. As Mao Zedong said, one must seize the moment. In the same period, intellectuals started to demand their country's "right to speak" and defended the existence of a "Chinese model."

In 2009, Liu Yang, one of the authors of China Can Say No and Unhappy China, published China Has No Model, arguing that the country must now find its own path. To do so, it must re-engage with its traditional philosophy—in particular, Confucian morals and ethics, the opposite of capitalist interests.

The prosperity brought about by Deng's reform policy had led to issues of corruption and social inequality. But it had also allowed China to rediscover its strength. Above all, it had convinced the majority of the Chinese people that Western culture was unsuitable for their country. Four years before Xi came to power, Liu was already evoking the "Chinese dream," which must "be extensive and belong to all of humanity."

Like Liu, Xi maintains a positive way of speaking about the culture and China's exceptionalism. If China is not Europe, why should it be a democracy, a system born in a world so far removed from China? In a 2014 speech reminiscent of Mao, Xi referred to the German philosopher Karl Jaspers and his "Axial Age" concept, popular in the 1950s but since obsolete: the idea that the world had known a period, similar to a dawn of civilization, when powerful cultures had emerged all over the world.

In developing this concept, Jaspers had tried to find a possible unity in global humanity. Xi, on the other hand, saw a subtle means of presenting China as a civilization apart, to justify its unique development. The common ground of humanity in Jaspers's original work has clearly given way here to an exclusive conception of civilization, impermeable to cultural mixing and outside influences.

Professor Zhang Weiwei of Fudan University, Shanghai, is among Xi's key influences. Zhang, like many of his colleagues, argues that China will be the one to influence the world. For him, we are moving away from a vertical world, with the West at the top, to a horizontal world, where all countries, including China, will be equal to the West in terms of wealth and ideas. "This is an unprecedented shift of economic and political gravity in human history, which will change the world forever," he has said.

The good news, according to Zhang, is that Xi will be the man implementing this new paradigm. "Many countries now turn to China for inspiration, for it has been far more successful than many others over the past 40 years, in particular when dealing with issues such as eradicating poverty and the emergence of the largest middle class in the world."

In the face of the challenges of globalization, then, it is a question of not a "Chinese model" but the "Chinese solution"—an expression that Xi used for the first time in July 2016, in a speech marking the 95th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.

Conveniently, the Western model is running out of steam, and not just because of the 2008 financial crisis. Democratic fatigue is spreading throughout Europe. Inequalities are rising, and the "losers" of globalization are ready to vote for parties that promise a strong state.

In the United States, the election of Donald Trump revealed just how unpredictable democracy can be. The Chinese media gladly seized on this perfect opportunity. In October 2016, the People's Daily claimed that the "U.S. presidential election chaos exposes a flawed political system." Ramming the point home, it even presumed to lecture the Americans, counseling them to "take a close, honest look at [their] arrogant democracy."

For many years now, the Chinese state has responded to Washington's annual report on human rights in China with its own counter-report. In these rebuttals, the government scrupulously outlines all of its rival's flaws: growing insecurity, a rise in gun crime, increasing racial discrimination and economic inequalities—all of which undermine the United States' claim of being the land of the free.

The notion that the global democratic system has many faults is gaining ground, and, luckily for Beijing, it is increasingly easy to convince the masses of it. Xi is not the only international leader promoting an alternative model, and this is certainly a development of the 21st century. Xi's solution strongly resembles the authoritarian propositions of Russia's Vladimir Putin, Hungary's Viktor Orbán and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Are we now hearing the opening bars of an illiberal "Internationale"?

If Europe tolerates the emergence of Xi's autocratic experiments, as well as his insistence that China is a credible world power, there is nothing to hinder the expansion of the Chinese model. The proof of China's efficiency—and its particular benevolence toward Europe—is in the Belt and Road Initiative, the multibillion-dollar infrastructure effort spanning Central and West Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Under Xi, in the space of a few years, China has greatly increased its presence in central and Eastern Europe, making the most of the EU's apathy toward this advance. The Balkans, an important crossroads between Asia and Europe, is the target of choice: In 2014, Beijing promised a $3 billion investment fund, a year after offering a credit line of $10 billion. Vuk Vuksanovic, a researcher and former Serbian diplomat, explained the strategy in 2017: "While Westerners have generally viewed the Balkan region as a nuisance—an ethnically fragmented territory on the periphery of the Euro-Atlantic world—China thinks of it as a conduit to European markets, as well as a way to project its soft power and buy friends among new EU members and potential membership candidates."

It seems that Xi is saying, "Yes, we can." China now prides itself on being the only world power able to stand up to the United States, culturally, economically and militarily. This global leadership has shown itself in unlikely areas: Civil servants from nondemocratic African or Southeast Asian countries, for instance, are sent to Beijing for propaganda training.

Further evidence of the success of Chinese soft power could be seen in the first couple's visit to the United States, in April 2017. They were invited to Trump's Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida, where the American president's young granddaughter performed a Chinese song. Her parents were proud to show off her progress in Mandarin. This scene, innocent as it may have seemed, could soon become the symbol of a geopolitical turn, with China supplanting the U.S. as the dominant superpower.

Having targeted China during his presidential campaign—"We can't continue to allow China to rape our country, and that's what they're doing. It's the greatest theft in the history of the world," Trump declared in May 2016—the U.S. president eventually had a change of heart. His first encounter with Xi was not the violent clash predicted: Trump was full of praise in an interview with The Wall Street Journal: "We have a great chemistry together. We like each other. I like him a lot. I think his wife is terrific."

Xi had given Trump a brief history lesson on Chinese–North Korean relations. "After listening for 10 minutes, I realized it's not so easy," Trump admitted, referring to North Korea.

Trump is the question mark here. Xi, an avid player of Go, the ancient game of strategy, has laid out his pieces on the board. Perhaps volatility is Trump's strategy, or he could just be a paper tiger who will let Xi surround him.

Donald Trump came to power aiming to "make America great again." Presenting his national security strategy in December 2017, he identified China as one of the "rival powers" who "challenge American power, influence and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity." But he also argued in the same speech that strategic cooperation between the two countries should continue.

Tensions remain, giving rise to rumors, not all of them nebulous. In the summer of 2016, a report by the RAND Corp., a respected think tank close to U.S. military circles, noted that war was improbable but not implausible.

From Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping by François Bougon. Copyright © 2018 by François Bougon and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.