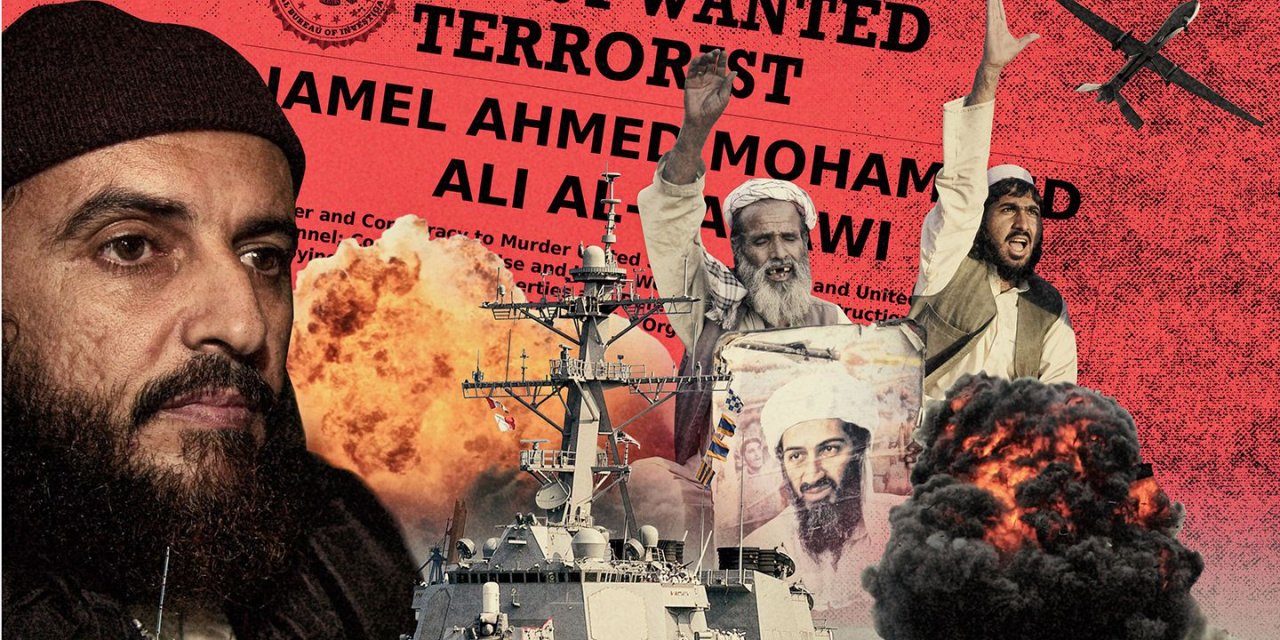

When reports arrived in early January that Jamal al-Badawi, a long-sought Al-Qaeda militant, had been incinerated in a U.S. airstrike in Yemen on New Year's Day, President Donald Trump let out a whoop.

"Our GREAT MILITARY has delivered justice for the heroes lost and wounded in the cowardly attack on the USS Cole," Trump tweeted on January 6.

Badawi, at large for over a decade, had quarterbacked the October 12, 2000, attack on the guided-missile destroyer with an explosives-laden boat as it lay at anchor in the Yemeni port of Aden.

The Pentagon had taken nearly a week to verify the news, perhaps keeping in mind that many a top terrorism target, including Osama bin Laden and Islamic State leader Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, were once declared dead, only to pop up later. "U.S. forces are still assessing the results of the strike following a deliberate process to confirm his death," a spokesman for U.S. Central Command had said. Days later, however, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the Yemeni-based organization whose membership has quadrupled in recent years, eulogized Badawi as "a martyr" who had indeed died from "a Crusader drone strike."

The demise of Badawi, held responsible for the death of 17 sailors and the wounding of 40 more aboard the Cole, came as bittersweet revenge for the Pentagon, CIA and FBI. They had hunted him following his repeated escapes from Yemeni prisons in 2003 and 2006, as well as after he was released by authorities in 2007 on a promise he would refrain from further violence.

"I dealt with Jamal Badawi for a long time," tweeted former FBI special agent Ali Soufan, who cracked the top bin Laden lieutenant way back in 2001 through a skillful, nonviolent interrogation, only to see him back on the street again and again. "We had to hunt/arrest him few times because he kept 'escaping' from his Yemeni jail." Soufan wrote, "He won't be escaping anymore."

Former officials say the end of Badawi marks a victory despite the time it took. "The important thing is that American intelligence and the U.S. military ultimately stayed on the case and delivered," says George Little, a former spokesman for CIA Director and later Defense Secretary Leon Panetta. "It's always a plus when we get someone who has been out of the newspapers for years," adds Daniel Benjamin, the State Department's coordinator for terrorism in Barack Obama's second term, "because it sends the signal that we do not forget."

But to Benjamin and several other former officials, Badawi's belated death also spoke to the worsening plight of U.S. counterterrorism missions abroad: America has fewer friends in the most troubled parts of the world than it did after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

"There's no question that a much more chaotic situation has developed, especially in Yemen," Panetta tells Newsweek. "To conduct really effective counterterrorism relations requires good relationships with [local] counterparts. It's become much more hit-and-miss now."

Badawi's time at large "underscores the difficulty in locating senior Al-Qaeda leaders not only there but in Pakistan, Syria, North Africa and East Africa, despite the use of all our available intelligence assets to find them," says Martin Reardon, a former senior FBI special agent who spent years pursuing terrorists. "It's also worth noting that in the countries where Al-Qaeda is most active—Yemen, Pakistan and Syria in particular—large swaths of ungoverned territory is under their control."

Pakistan sheltered bin Laden for a decade and continues to support the Afghan Taliban and other groups fighting the U.S.-backed Kabul government, which is riddled with enemy spies and "insider" agents. In October, a Taliban gunman nearly killed the U.S. and NATO commander there, General Austin Miller. In U.S.-backed Iraq, the regime's Shiite paramilitary groups are allied with Iran. Turkey, a titular NATO ally, is vowing to destroy U.S.-backed Kurds that have led the fight against the Islamic State militant group (ISIS). Jordan is growing restless over the Trump administration's embrace of Israel's hard-line policies against the Palestinians.

It was also Jordan's intelligence service that a decade ago gave the CIA an agent who pretended to have infiltrated bin Laden's inner circle. On December 30, 2009, he was welcomed into a CIA base in Afghanistan wearing a concealed suicide vest and blew himself up, killing seven Americans, a Jordanian and an Afghan, as well as seriously wounding six others.

Over 17 years after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in pursuit of bin Laden, and almost 16 years after its tragically mistaken invasion of Iraq to get rid of Saddam Hussein and his nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, the region is more dangerous than ever to Americans on the ground.

Obama, like his predecessors, put "a premium on partnerships—training and equipping our allies and friends' forces to be the pointy end of the spear so that U.S. forces need not play that role," says Edward "Ned" Price, his former national security aide. But a major strategic problem for Washington, then as now, is that many of its longtime regional intelligence allies, like Egypt, have infamous records of repression and brutality, not to mention corruption. Jailing dissidents, human rights activists and journalists has turned prisons into universities for jihad; Ayman al-Zawahiri, the onetime surgeon held in Tora Prison, on the outskirts of Cairo, became a founder of Al-Qaeda (and remains at large, likely in Pakistan). U.S. partnerships with such regimes have helped Islamic militants rebrand themselves as global revolutionaries in an arc from Indonesia through the Middle East to West Africa.

Regimes like those in Saudi Arabia and Yemen (under Ali Abdullah Saleh, assassinated in 2017) long ago learned how to play both sides of the street with their American partner, aiding Islamic extremists with one hand while arresting them with the other. "In Yemen, it wasn't ideology that was the problem" in keeping Badawi in prison, says Benjamin, now director of the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth, "just the unstoppable urge of Saleh to diddle us."

"A reliable ally is a great asset," former M15 and M16 counterterrorism officer Richard Barrett tells Newsweek. "But an unpredictable or manipulative one can be worse than no ally at all."

Lisa Monaco, a veteran Justice Department national security official who rose to chief counterterrorism adviser to Obama, sounded deeply gloomy in a recent interview about U.S. prospects in the region. "The bad news is that the conditions that made it possible for Al-Qaeda to take root, that made it possible for ISIS to expand and occupy the territory to recruit and radicalize, all of those things still exist in the Middle East [and] other regions," she told former CIA Deputy Director Michael Morell on CBS's Intelligence Matters podcast. "And those things are not going away. In fact, they're getting worse—if you look at places like Yemen."

Trump's Muslim ban has made it harder to make new friends in the region, she says. "It sends an isolating message that we don't want to work with Muslim countries and that fuels ISIS recruiting." Panetta says that Trump's impulsive statements about exiting Syria within 90 days and Afghanistan by 2020 further unsettled allies: "Nobody knows if we're going to be there tomorrow."

All of which "makes it harder for security services to be seen as partnering with Americans in joint training or operations," says Price. These partnerships, Monaco told Intelligence Matters, are "critical to being able to take the fight to the terrorists abroad before they come here."

There are workarounds for the U.S. in dicey places like Pakistan, Jordan, Lebanon and Somalia, where CIA and clandestine Pentagon teams can try to mount so-called unilateral intelligence operations, kept secret from host authorities. But they are difficult and dangerous, and exposure can strain alliances to the breaking point.

Price notes that "there are very few around the world who we'd consider consistently reliable" partners. But he insists that many have gotten better, citing "Somalia, Nigeria and other parts of West and North Africa." In the end, he says, "improvement tends to be the name of the game."

Robert McFadden, a 30-year Naval Criminal Investigative Service counterterrorism vet, spent two months interviewing Badawi when he was imprisoned in 2007. He isn't so optimistic, but he'll settle for wiping out an Al-Qaeda kingpin who had continued to plot attacks against the U.S.

"Though an airstrike doesn't do anything about terrorism's incubators," McFadden says, "it does show that if you remain in the jihad life, violence will be lurking." Justice delayed, he adds, is better than no justice at all.