On a gray, rain-soaked day in December, British Prime Minister Theresa May pulled up to the entrance of German Chancellor Angela Merkel's office in Berlin. The embattled May was on a tour of European capitals in a desperate bid to win further concessions for her Brexit deal after putting off a parliamentary vote on the proposal to avoid a certain defeat.

As Merkel stood outside on a red carpet waiting to greet the British leader, an official tried to open the door to May's black Mercedes, only to find she was locked inside. After several unsuccessful tries, the official finally got it open.

Some pundits saw symbolism in May's awkward arrival, interpreting it as yet another sign of her political and personal struggle to implement Britain's 2016 decision to leave the European Union, a move she opposes. British critics of the EU recalled earlier remarks by Michael Gove, her pro-Brexit environment secretary, who had warned that if Britain remained in the EU, its citizens would be like "hostages locked in the back of a car."

Though May won no new concessions on that trip, she did succeed in convincing Merkel and other European leaders to embrace her original plan for a so-called soft Brexit. It included, among other things, a gradual British exit from the EU, reciprocal protections for British and EU citizens living in each other's countries, and a method to prevent the return of a physical border between Northern Ireland, which is part of Britain, and the Irish Republic, which will remain a member of the EU.

But May had no such luck back home. On January 15, the House of Commons rejected her plan by a vote of 432 to 202, delivering the biggest parliamentary defeat for a prime minister in modern British history and leaving the country in stark political disarray. With May's Conservative Party split over Brexit and no consensus in Parliament around a single blueprint for withdrawal, the process returned to square one, with various political factions once again putting forward their plans, just as they had after the referendum two and a half years ago. May survived a vote of no confidence the day after her Brexit defeat, but analysts say that as long as the Brexit issue remains unresolved, she will remain a wounded and weakened leader.

"A defeat of previously unimaginable proportions…has left the country adrift, floating toward no deal, with no party or faction in Parliament able to command a majority for any way of moving off the course it has set for itself," wrote Politico's chief U.K. correspondent, Tom McTague. "Faced with disaster, Theresa May has a plan but no strategy—the Churchillian maxim 'Keep buggering on.'"

If there's one European leader who can feel May's pain, it's Merkel. Both are strong female leaders who have championed the value of a united Europe under the auspices of the EU. The idea for an economic partnership among European nations sprang from the horrors of World War II, based on the notion that countries that trade together were less likely to go to war with one another, as they had for centuries in Europe. Since then, internal borders have come down between the EU's 28 member states, allowing people and goods to move freely as if these states were one country. The EU also has grown into a political partnership, with its own Parliament in Brussels that sets regulations for all its members. And the continent has been largely at peace.

Ironically, it is Merkel and May—two staunch defenders of European integration—who may be responsible for what many fear is its looming disintegration. Critics say both leaders misjudged their countries' non-elites for whom identity politics and economic hardship trumped commitments to European unity. They cite Merkel's mistaken assumption that most Germans would welcome the masses of refugees from the Middle East and Africa whom she gave political asylum in 2015. And they point to May's misplaced confidence, after she grudgingly agreed to implement the Brexit vote (she had voted against the referendum in 2016, before becoming prime minister), that Brexit supporters would embrace her plan for a kinder, gentler departure from the EU. Instead, Merkel and May got a rising tide of nationalism and anti-immigrant xenophobia that has polarized politics in both countries, reducing the leaders' personal stature and leaving the future of the EU in doubt. Some far-right figures in Germany are now talking about a "Dexit"—short for Deutschland's exit from the EU.

"For the first time in my professional career, I'm afraid—existentially—for Europe," Charles Kupchan, President Barack Obama's top National Security Council adviser on European affairs, tells Newsweek.

Charity Blowback

May's current predicament, some analysts say, can be sourced back to Merkel's decision to open Germany to more than 1 million refugees and devote billions of euros to their housing and care.

While many world leaders initially praised Merkel's move as an admirable humanitarian response to the continent's burgeoning refugee crisis, it ultimately changed the political face of Europe, inflaming anti-immigrant passions in countries like Hungary and Italy, where authorities found themselves overwhelmed by the refugee onslaught. Far-right parties across the continent grew in strength, particularly after foreign nationals were found to be among those who sexually assaulted women on the streets of six German cities during 2016 New Year's Eve celebrations.

In Britain, where conservatives have long chafed under EU rules regulating the environment, transportation, consumer rights and even cellphone charges, the refugee crisis prompted vigorous pushback—along with anti-Muslim demonstrations by right-wing groups—against the EU's open-border policy. The complaints and protests eventually resulted in the 2016 Brexit referendum.

In the run-up to the referendum, May, then the home secretary, stressed the economic benefits of EU membership. But after Prime Minister David Cameron lost the Brexit vote and resigned, she took over the government and pledged to carry out the withdrawal, which she said reflected the will of the people. Even then, however, she labored to soften its impact by setting a two-year timetable before withdrawal, winning numerous concessions from EU leaders.

What happens going forward is unclear. Analysts point to several possible scenarios, and their range only highlights Britain's political chaos. The country could leave the EU without a deal—the so-called hard Brexit preferred by former Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson. But such a move lacks majority support in Parliament, largely because it would take a heavy economic toll. A Bank of England report late last year predicted that a withdrawal with no deal would result in an unemployment rate of 7.5 percent, a 30 percent drop in housing prices and a major devaluation of Britain's pound currency, producing an economy that would shrink by 8 percent by year's end.

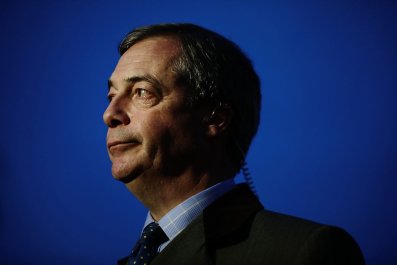

A second scenario: Britain could hold another Brexit referendum. Some former officials believe this is a strong possibility, predicting the country, having tasted the stock-market declines that the Brexit vote has already caused, is likely to choose this time to remain in the EU. But hardcore Brexit supporter Nigel Farage predicts his followers would crush another referendum. "British voters will be even more defiant in a second poll and will vote to quit the EU by a bigger majority," he tells Newsweek. (See page 26.)

As a third possibility, May's fellow conservatives could remove her from office and choose a leader who would try to reach some as-yet-undefined new deal with the EU. According to the BBC, Tory members of Parliament who oppose her say they're close to gathering enough signatures to initiate a party no-confidence vote.

For now, however, the most likely scenario is an attempt by May to persuade the EU to delay the official Brexit date of March 29 by several months; that would give her time to renegotiate a deal that has a better chance of passing Parliament. "Realistically speaking, the only way to get the major changes on the controversial issues would be to re-open Brexit negotiations with the European Union" and extend the deadline, wrote Christopher Stafford, a political scientist at the University of Nottingham, in an online analysis.

Meanwhile, the deep divisions plaguing May in Parliament are showing up on the streets. As she painstakingly negotiated her proposed Brexit deal, far-right groups gathered daily outside Parliament and harassed members who supported remaining in the EU. In December, in London, anti-Muslim activist Tommy Robinson led thousands of hard-line supporters of the right-wing U.K. Independence Party in a "Brexit Betrayal" demonstration against May's plan, calling her a "traitor" and brandishing a portable gallows.

"This is the politics of pure antagonism, the politics of populism," wrote Alex Oaten, a political science professor at the University of Birmingham, in an online commentary. "Brexit has unleashed an 'us' and 'them' mentality that is dividing our democracy along increasingly antagonistic fault lines."

A Spreading Infection

Germany's fragmentation has been well underway for several years now, also driven in large part by Merkel's generous refugee policy. The huge sums she provided for their absorption rankled many middle- and working-class Germans who have watched their standard of living decline over the past two decades due to stagnant wages and job insecurity, according to a 2016 study published in the Journal of Global Ethics.

The country reached a political tipping point after the 2016 New Year's Eve assaults. According to a leaked police report, as many as 2,000 men assaulted 1,200 women, raping 24. Of the 120 suspects police identified, about half were foreign nationals who had recently arrived in Germany. In response, anti-immigrant sentiment soared, energizing the far-right Alternative für Deutschland party, especially in the east, where the lagging economy amplified popular resentment toward the refugees. In the 2017 election, the AfD, which includes neo-Nazis in its ranks, emerged as the country's third-largest party in the nation's parliament, effectively the opposition.

Until then, Germany's electorate, with its heightened sensitivity to far-right movements due to the country's Nazi past, had withheld meaningful support for the AfD, consigning it to the political fringes. But with the AfD's success in the 2017 election, "Germany has now become just another European country," says Sudha David-Wilp, deputy director of the Berlin office of the German Marshall Fund, a think tank focusing on trans-Atlantic issues. The country, in other words, is joining France, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Poland, where far-right and anti-immigrant parties have gained power or grown significantly in strength.

Since 2005, Merkel had led her centrist Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party to solid victories in three previous elections, but she barely won the 2017 vote, then struggled for a full six months before finally forming a coalition government. When her partners suffered a stinging defeat in regional elections this past October, she decided to step down before she was pushed out.

At a Berlin news conference a few days after the elections, Merkel announced she would immediately retire as her party's leader, a position she had held for 18 years, and would not run for a fifth term as chancellor. "The time has come," the 64-year-old Merkel told her followers, "to open a new chapter."

But not just yet. Merkel also said she intends to serve out the remainder of her current term as chancellor, which means she could remain at Germany's helm until 2021. Meanwhile, Merkel's hand-picked successor, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, was voted the new leader of the CDU.

Assuming Merkel serves out her full term, she'll have one last opportunity to shore up Germany's weakened political center, fight back against the AfD's growing challenge and challenge the growth of similar movements across Europe. "She'll need to maintain her political clout in a Germany that's already contemplating the post-Merkel era," says Kupchan. "But her centrist approach to governance will be difficult to sustain [when the] political center is weakening. She'll also need to help keep Europe together at a time when populism is pulling it apart."

Steven Sokol, president of the American Council on Germany, a foreign policy advocacy group, says two upcoming elections will provide a barometer for Merkel's success or failure: the European Parliament elections in May, in which far-right and anti-immigrant politicians from all across Europe will challenge the continent's centrist figures; and Germany's regional elections this fall in three eastern states considered AfD strongholds. "Each of these elections will be a vote not only on a European-wide level and on a German state level," says Sokol, "but also a vote on Merkel."

Weathering the Shitstorms

Merkel also faces the very real possibility that President Donald Trump, who has complained loudly about the failure of European allies to pay more for their defense, could withdraw the U.S. from NATO, a move that would effectively kill the 70-year-old alliance. Senior U.S. officials told The New York Times recently that Trump repeatedly expressed his intention to pull out of NATO last year and might return to the threat after Germany and other European countries fail to meet his defense spending demands.

Trump harbors a particular antipathy for Merkel, not only over Germany's low level of military spending but also over her liberal policy toward refugees, which he, not surprisingly, regards as a major political mistake. This sentiment surfaced during Trump's presidential campaign in 2015, when he mocked Time for naming Merkel its Person of the Year in recognition of her refugee assistance. "They picked a person who is ruining Germany," he tweeted.

Though previous U.S. presidents have also complained about Germany's low defense budget, Trump used Merkel's first visit to the White House in early 2017 to humiliate and harangue her. Seated next to the German chancellor in the Oval Office, Trump pointedly refused to shake her hand for photographers. Later, after the press had left, Trump turned to Merkel and said, "Angela, you owe me 1 trillion dollars." According Ivo Daalder, Obama's ambassador to NATO, the figure had been compiled by Trump's aides to reflect how much European allies supposedly should have paid the U.S. in shared defense costs since 2006. When Merkel announced her intention to retire, Trump regarded it as a personal victory, his aides say. "The relationship between them is about as bad as it's ever been," Daalder tells Newsweek.

How Merkel manages the relationship with Trump, Kupchan says, is likely to determine the future of the trans-Atlantic order. "She'll have to fashion a new brand of statecraft that faces the reality that Europe's geopolitical anchor—the American security guarantee—may be coming unstuck," he says.

Merkel supports the formation of a European army, first put forward by French President Emmanuel Macron. "The times when we could completely depend on others are over," she said in a speech last year. "We Europeans must take our fate into our own hands."

That's a tall order. But as Merkel goes into the final stretch of her political career, she appears to be unshaken. Addressing a recent technology conference in Nuremberg, she paused to tell the audience about the time she had been mocked on social media a few years ago for describing the internet as a stretch of "unknown territory." In a self-deprecating moment, Merkel chuckled and remarked: "It generated quite a shitstorm for me."

That is perhaps the best description of what Merkel and May can expect in the weeks and months to come.