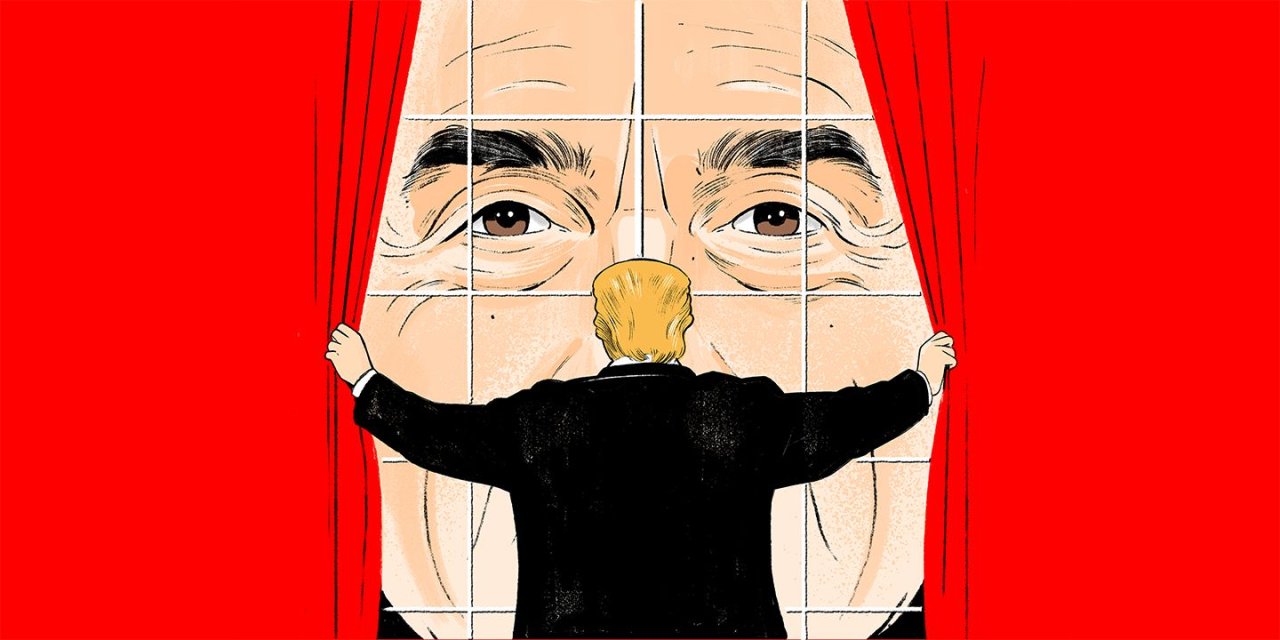

In tweet mode and at his "Make America great again" rallies, the president has spent the better part of the past 18 months attacking the "WITCH HUNT" against him. Meanwhile, special counsel Robert Mueller, a former FBI director, has run a tight-lipped operation. Other than the 33 people and three companies he has charged so far, almost no one, least of all the American public, knows what to expect as his investigation churns toward its presumed final target, an increasingly rattled President Donald Trump.

University of Arizona constitutional law professor and author Andrew Coan's new book, Prosecuting the President (Oxford University Press), provides historical context for Mueller's operation. Because government policy states that no sitting president can be indicted before he is impeached, Coan explains that the special prosecutor's relationship to the president is a complex combination of politics and law. For Mueller, unlike a court of law prosecutor, the chief duty is to focus public attention on wrongdoing. Acting on that information is left to the public and Congress.

As a target, Trump is in hallowed company. At least six U.S. presidents have contended with special prosecutors, beginning with Ulysses S. Grant in 1875 and including Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. Clinton was impeached by the House (but acquitted by the Senate). Nixon left office before impeachment could happen. But Trump has his own special reality, as Coan explains to Newsweek.

What is the legal basis for a special prosecutor? It's not in the Constitution, correct?

Correct. The special prosecutor has existed for 140 years, mostly appointed on an ad hoc basis when a president has needed a way to signal his seriousness about investigating allegations against himself or his administration. Mueller was appointed under a set of formalized regulations adopted in 2000, in the aftermath of Clinton's impeachment. They replaced something called the Ethics in Government Act, which itself was adopted in the aftermath of Watergate and established a much stronger special prosecutor than we have today, one who could not be easily fired. Many people on both sides of the aisle thought that the special prosecutor was too strong. For Democrats, Exhibit A was Ken Starr [during the Clinton administration]. For Republicans, it was Lawrence Walsh spending seven years investigating Iran-Contra [during the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush].

What's the special prosecutor's chief function?

At their best, they serve as avatars for the people, raising the visibility of allegations and putting pressure on the president. But at the end of the day, the final decision about whether to impeach and remove a president is a political decision.

Why can't a sitting president be indicted?

The Constitution clearly states that a president can be subject to criminal indictment after impeachment. Whether the founders intended that to be exclusive—meaning that a president or any other official can only be indicted after being removed from office—is subject to debate. The main argument for permitting indictment only after removal is that indictment would fatally impair a president's ability to carry out his constitutional duties. It would be inconceivable, for example, that marshals would arrest a president in the middle of a phone call with a foreign leader. Nor could a war be run from a D.C. jail.

If a president can't be indicted, how is the American system any different from a monarchy?

Because a monarchy has no system of impeachment. The real question is not whether a president can be removed from office or indicted, it's who should exercise that power—Congress? Or 19 citizens on a grand jury?

Are these prosecutors always apolitical? Or is Trump right that this one is a witch hunt?

I believe Trump is the first president to personally use the words witch hunt, but presidents have a powerful political incentive to undermine a special prosecutor's credibility. Attacking the prosecutor is extremely common—though, unlike Trump, past presidents rarely got involved in the attacks themselves, instead delegating that to subordinates.

Charges that the special prosecutor is overzealous or has gone off the rails have been commonplace in the past, but usually they have been tools of presidential propaganda. It's a judgment call, but there have been only a few serious cases of overzealousness. One would be Ken Starr's sprawling investigation of Bill Clinton. Most observers, across the political spectrum, came to regard it as demonstrating a serious failure of prosecutorial judgment.

Based on what he's done so far, do you think Mueller believes Trump can be indicted?

The answer is no, he doesn't. In addition to constitutional issues, there is a Department of Justice [DOJ] policy—that the president may not be indicted—which Mueller is bound to.

You write that prosecutors are appointed to bolster "public confidence" in the government. Hasn't Mueller, after 18 months and 33 indictments, already diminished public confidence in this government?

The alternative is not investigating serious charges at all or entrusting investigations to the DOJ, which operates under one of the president's political appointees. Special prosecutors promote confidence that misconduct will be investigated thoroughly and impartially.

Since Mueller can't actually indict Trump, isn't the investigation ultimately a political activity?

I don't think the answer is either/or. A special prosecutor is both a legal and a political actor. His job is to raise the visibility of allegations of serious misconduct in a way that focuses public attention. But the law has a really robust role to play. The president's son could be charged with crime. His former national security adviser and campaign director are already charged with crimes. The formal legal tools Mueller has at his disposal enable him to play this political role in highlighting allegations. That probably wouldn't have happened without a special prosecutor.

The endgame for the president is different—the political process of impeachment. But even that takes place in the shadow of the law. If the president has broken the law, that matters politically, and a special prosecutor may be the only way the public finds that out.

If he finds wrongdoing on Trump's part, how will Mueller present it since he can't indict?

He could say there is evidence supporting a charge of obstruction of justice for anyone but the president of United States. He could say there is evidence that supports charges of a criminal conspiracy to defraud the U.S. against any other defendant but the president. That will be meaningful as Congress decides whether to move forward with impeachment.

What are the chances that the administration might try to keep Mueller's report from the public?

He is required to submit a confidential report to the new attorney general, William P. Barr [expected to be confirmed by February], explaining his decisions on criminal charges. If Mueller turns up significant evidence against Trump, it's highly likely he'll say that he chose not to bring criminal charges because of the rule against indicting a sitting president. Alternately, he might present the evidence without reaching any conclusion.

Once Mueller delivers that full report, there will be intense political pressure on the attorney general to release it. The president's attorneys are already working hard to develop legal arguments that certain evidence might be protected by executive privilege. The lawyers will make that argument to Barr as a way of informing his decision on whether to release the report to Congress or the public.

Congress has tools if Barr decides to withhold. The House has the power to subpoena documents from the executive branch. If the executive branch can resist, a court battle might well ensue between the House and the DOJ. Congress can also call Robert Mueller and his staff to testify.

If Barr tries to suppress the report, the probability of it leaking is high, even though Mueller's team has been extraordinarily tight-lipped. The question is how far Barr, a well-respected establishment lawyer, would be willing to go to suppress damning evidence—if there is any—against Trump. The report will get out someday. Will he want to be remembered as Trump's bagman?

How do the personal attacks that Trump lobs against officials affect Mueller's ability to do his job?

They go to the heart of the prosecutor's ability to do his job. Other presidents have pushed back, but what we have seen in Trump exceeds all others—not only in vituperation but in his personal involvement, which is really important.

If he can't be indicted, and he's not impeached, can't Trump run out the clock and stay president?

It is very plausible to imagine a pretty damaging report which is not damaging enough to set impeachment wheels in motion. And if he runs again and wins, he will lengthen the period during which he cannot be indicted to the end of a second term. He will be old by then [78], so he will have run out the clock in a real sense.

You end your book with the section "America, the Vulnerable." Why? And vulnerable to what?

The U.S. is more vulnerable to a norm-smashing, rule-of-law-breaking president than at any other point in my lifetime. There are two structural changes in American politics undermining the ability of the special prosecutor to hold a president accountable. One is the extreme polarization of American politics, which means that every question is seen through a partisan lens. It is very hard for the American people to impartially ask themselves, "Has this president, in fact, committed criminal wrongdoing?"

The second is the populist moment we are experiencing. By this I mean the personal connection Trump has with his supporters and the license that this connection gives him to smash through norms which would have constrained other politicians. No other president would have survived mocking a war hero like John McCain or encouraging supporters to physically rough up protesters.

When a president doesn't feel constrained by norms, it is much harder for special prosecutors to focus attention on these issues and for the public to judge the president impartially.

If the prosecutor's role is to "focus attention" on criminal wrongdoing, then the media is part of the delivery chain, correct?

The media is crucial and not just in raising public awareness of the special prosecutor's work and political pressure [on him]. For instance, that story about senior FBI officials who wanted to look into whether Trump is an agent, unwitting or not, of the Russians—that is really shocking. But we have no idea what they concluded, or what Mueller will conclude. On that point, and many others, we are in the dark. A special prosecutor is often the only one who can credibly answer these questions.