As a young man working at Newsday in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Robert Caro caught on to something that his peers seemed to be missing: True political power doesn't come from voters or televised congressional hearings. Exhibit A was Robert Moses, the master builder who spent billions creating nearly every piece of modern infrastructure in and around New York City—without once facing a public election.

Fascinated, Caro would go on to research and write The Power Broker, the seminal, award-winning biography of Moses, and began a nearly 60-year investigation into what power is and how it's obtained. His revered 1,000-page tomes about President Lyndon Johnson would follow, but his career as America's authority on political power almost didn't happen.

"Robert Moses didn't want me to write about him and really had me stymied," Caro tells me on a brisk March morning. "Moses kept all of his papers on Randall's Island, and there were guards everywhere."

Then he got a phone call from Mary Perot Nichols, a former muckraking columnist and city editor of The Village Voice who, at the time, was working as director of public relations for the New York City Parks Department. It just so happened that there were copies of Moses's files sitting in a basement in Central Park. "She said, 'I know where his papers are, and I can get you the key.' That was one of the great moments of my career."

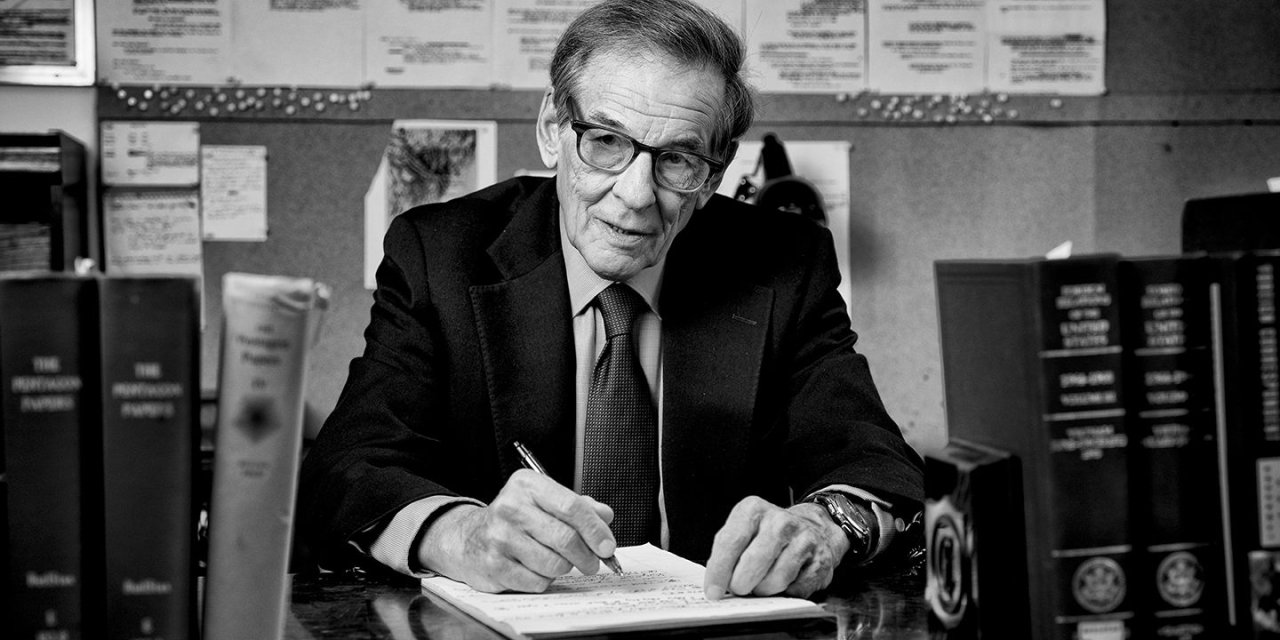

Caro delves into the stories behind his best-sellers in his new book, Working, which is composed of essays and repurposed interviews that give insight into one of the most celebrated minds in American letters. The 83-year-old author has a lengthy memoir planned for later but wanted to get something out quickly—you know, just in case. "I can do the math," he says.

Caro still handwrites all of his books before typing them up on his gray Smith Corona Electra 210. He purchased 17 of them when they were discontinued 30 years ago, and now he's down to 11. When I meet with him, he sits on one side of his very large desk next to the handwritten pages of his next book, the fifth and final volume in the definitive biography of America's 36th president. Behind him, pinned to a large corkboard, is the book's outline. He tells me to not look at it too closely.

Clad in a red cashmere sweater and tortoiseshell glasses, the octogenarian likes to do things the old-fashioned way. (When his wife and longtime research partner, Ina, calls, he can't figure out how to answer the phone.) It's his commitment to turning every (physical) page that keeps his fans waiting years for each new book, and his penchant for detail and mise-en-scène has gained him a cult following among history buffs and literati alike.

I met with Caro at his office, a repurposed three-bedroom apartment (the kitchen, he tells me, is just for coffee) across the street from Central Park, to discuss his approach to power, the current political climate and how Johnson almost didn't become president.

This book is pretty out of character for you; it's only 207 pages. Why did you decide to keep it so short?

My books are about political power, and I think it's important that people understand how it works in America. But I think I've learned some things while researching and writing about how you learn about political power. I took a few months out from doing the Lyndon B. Johnson books to put a few thoughts down on paper.

Have you always had confidence in yourself?

Confidence doesn't have anything to do with it. I didn't know I wanted to be an investigative reporter. When I started going through files for the first time, I said, "Oh, I love doing this." Why do I love doing it? I don't think I've figured it out yet.

You study power, and you've been around a lot of powerful people. Have you ever been intimidated by them?

No, I never did feel intimidated.

You talk to these people who hold so much power, yet you hold this power over them as a reporter.

I have power over them? That's not a thought I entertain. You're just trying to describe what they've done. It's more like you're thinking, Oh, it's going to be so hard to describe how they did this.

You talk about moments when you were brought to tears by the fate of Moses and the childhood of Johnson. Clearly, you see the good in complicated figures. Is that how you approach the current situation in Washington, D.C.?

I'm fascinated by what's going on in Washington right now. It's never been more important that people understand how the political process works. What the Senate and House do now to counter this president is really important.

There's this immense propensity of government to affect people's lives—to help them by bringing [them] electricity, voting rights and civil rights—and an immense capacity to injure people, like running highways right through their neighborhoods or [sending them to fight in] Vietnam. But people today have forgotten the power of government to do good.

I have an eye problem, and there's one clinic in New York with a specialist for it. When I got there, the waiting room is this huge room, and the first thing I noticed is that I was the only white face in this entire room; there were a lot of mothers and people of color and a lot of kids with very thick, Coke-bottle glasses. I asked my doctor, "Before Medicare and Medicaid, what percentage of these kids would have been here?" He [looks] surprised and says, "Absolutely none. They wouldn't have been able to afford this."

So look what Medicare and Medicaid did. This is one example; multiply it by thousands, you know? That's the power of government.

You posit that Lyndon Johnson won his 1948 Senate race only because the Democratic primary was stolen. Did that challenge your belief in our system of government?

It cast a real light for me. I wanted to write a book about the political system, and stolen elections are a part of our political history. I thought I knew something about politics and power, but I'm constantly finding out how little I know about it.

Would Johnson have become president if not for that stolen Senate election?

He regarded that Senate run as his last chance; he was going to retire from politics if he lost. And the fact is, he lost. But he didn't retire from politics because of this election, and he went on to become president. As a result, we had this huge escalation of Vietnam and the human suffering that it caused. On the other hand, we have Medicare and Medicaid and voting rights. That election was a very pivotal moment in American history.