For Donald Trump, the politics of trade always seemed straightforward.

Ripping pretty much any other country with which the U.S. runs a trade deficit—and China, trade villain No. 1, in particular—was a way to win hearts and minds of voters throughout the industrial Midwest in 2016. When it turned out that those voters, in states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, would unexpectedly give him the presidency, Trump's instincts—his gut—were ratified. "I won," he once told his friend Tom Barrack, a prominent investor and Trump campaign fundraiser, "because of trade."

What Trump didn't understand that night, according to friends, associates and people who work for him today in his administration, was how complicated the issue of trade is. As a businessman and self-described deal-maker of unparalleled excellence, he felt the imposition of tariffs on major U.S. trading partners would give him precious "leverage" in the negotiations that would follow. And to Trump, leverage is the coin of the realm. "I'm a tariff guy," he would say to journalists and anyone else who would ask, in part because he believes they give him bargaining power. "I'm using [them] to negotiate," he told The Wall Street Journal last year.

But the president didn't impose tariffs on just China; he slapped levies on traditional U.S. allies such as Canada, Japan, South Korea and the European Union. Unsurprisingly, this freaked out pretty much anyone with a 401(k). While the investor class (a traditional GOP constituency) loved Trump's economic policies of tax cuts and deregulation—so much so that they drove up stock prices pretty much from election night onward—they hated trade conflict. As an analysis by economic advisory firm IHS Markit showed, the markets reacted badly whenever trade war headlines were prominent, bouncing back whenever it seemed like resolution was at hand.

Thus was born the central economic policy debate of the Trump era, one that rages to this moment in the White House: Trump may be a self-professed "tariff guy," but he also loves Wall Street, reveling in the fact that the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit record highs during his presidency. Advisers say he has been "relieved and delighted," in the words of Larry Kudlow, head of Trump's National Economic Council, that the stock market has recovered in the first quarter of this year after last December's sudden, sharp swoon, as global recession fears intensified. "What he has discovered," says one senior economic adviser who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the president's thinking, "is that it's very hard to have both a trade war and rising stock prices."

Trump's moment of choosing is at hand. For much of this year, Wall Street came to believe—based mostly on signals from Trump's economic advisers—that a deal with China on trade was imminent. Indeed, after a recent round of talks with their counterparts from Beijing, White House officials said a meeting between Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping would occur at the end of March, at which an overarching deal would be signed.

The substance of that deal, however, is very much in debate, as Trump's administration remains divided on trade. Though the White House publicly goes to great lengths to deny any internal strife—most recently, Kudlow went on Fox News Sunday to insist that economic advisers were all of one mind—it's not that simple. Kudlow, like his predecessor, former Goldman Sachs Chief Operating Officer Gary Cohn, is a relative dove on trade, pushing for an agreement with China sooner rather than later, arguing to Trump that the stock market—and the economy more broadly—would react positively once the trade issue was in the rearview mirror. He's joined in that assessment by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and Council of Economic Advisers chief Kevin Hassett.

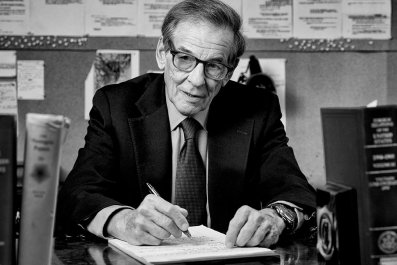

But Trump's main adviser on this issue, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, is urging the president to be patient, believing the U.S. can get a better, more comprehensive deal with Beijing than the one currently on the table. In the most recent round of talks, sources on both sides say China offered the U.S. a reduction of tariffs on a broad range of imports, including automobiles, and pledged to buy significantly more American agricultural products and energy, as well as a commitment to import a massive amount of liquefied natural gas. That would ostensibly bring down the huge bilateral trade deficit with China and enable Trump to say during his 2020 re-election campaign that he delivered on his promise to get tough with Beijing.

In an Oval Office meeting with Trump in the first week of March, Lighthizer, according to multiple sources, said that deal didn't go far enough. Unlike any of his predecessors in the trade rep job, he has detailed what one White House source calls a "holistic" trade case against China's mercantilism: theft of intellectual property, subsidies to state-owned companies in key industries and requirements that foreign multinationals form joint ventures with domestic firms and share technology with them, as well as a variety of other traditional barriers, including tariffs. His influence with the president, says a friend of both men, is rooted in two things: Trump's own get-tough instincts on trade, and the president's belief that his trade rep is right "on most, if not all, of this stuff"—something much of Washington's economic establishment has come to believe.

Lighthizer has detailed what one White House source calls a "holistic" trade case against China's mercantilism.

Lighthizer has further argued that time is on Trump's side. While the U.S. economy remains relatively robust, China's is flagging, according to a slew of recent data—an intensifying hangover after years of debt-fueled growth. His message to Trump is clear: Xi, under political pressure at home (economic growth being the main source of the Chinese Communist Party's legitimacy), needs a deal more than you do. "Hang tough, and we'll get a better deal" is how one official describes it. Trump, for now, has bought Lighthizer's reasoning. He has not yet committed to a deal, which is a prerequisite for the Chinese to sign off on a Xi visit to Mar-a-Lago.

But, as the 2020 campaign gets underway, politics is very much on Trump's mind as well. He wants a campaign based on two overarching themes: widespread prosperity and living up to the core campaign promises he made in 2016. His key markers on the economy are the low unemployment rate and rising stock prices. "He checks what's happening in the stock market several times a day, almost every day," says a friend. "He sees it as a daily ratification of his [economic policies] when it's going up."

The comfort Trump takes from rising stock prices could be fleeting between now and the next election, though. Not only do markets always fluctuate, but they depend on rising earnings growth from corporate America, which requires a strong macroeconomic environment. Most economists expect a downshift in gross domestic product growth this year, as the stimulative effects of Trump's tax cut wear off, which could make it difficult for a sustained stock market rally.

His other obsession—the overall trade deficit—is also misplaced, as the most recent trade data demonstrated. Last year, the U.S. racked up its largest trade deficit ever, showing that macroeconomic conditions usually swamp specific trade policies. That the domestic economy was growing strongly in 2018, while major trading partners—China and Europe in particular—were slowing sharply, meant the U.S. bought more from them while their demand for our exports softened.

Still, Trump's political aides know he would like a rising stock market straight through 2020. They also know that the biggest risk to that would be ongoing trade conflict with Beijing. Key advisers in the White House, including Stephen Miller, senior adviser for policy, are pushing Trump to accept the deal that's more or less on the table now: increased agricultural and energy exports, which would help Trump secure his red state base (farmers, in particular, have been restive about his trade policies), and lower Chinese tariffs on autos and other industrial goods, which would help him to be competitive in the states he shocked the world by winning in 2016: Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Approval ratings in those states have since sagged.

Trade hawk Lighthizer may have brought a compelling, lawyerly case against China's multiple trade abuses, but the only jury Trump cares about is the electorate. And that means, sooner or later, he'll do a deal with Beijing and declare victory—warranted or not.