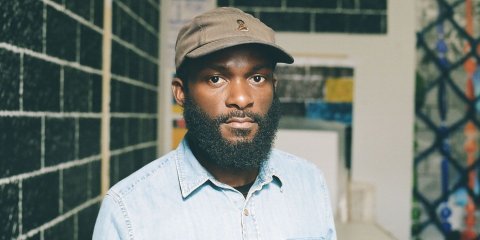

On the morning of his first major show, Paul Anthony Smith is nervously watching gallery assistants hang a few last pieces. "I've been working on this since last fall," says Smith. "Having the works here—it looks strange. I'm letting everyone into my world. They're not just mine anymore."

The artist, based in Brooklyn, New York, is trying not to think about the possibility that some might be sold. "I love everything I do, so I get a little annoyed when someone buys a piece. Letting go is the hardest part," he says. "So then I make another one."

Smith joined Jack Shainman's gallery last October, and this show, called "Junction," will occupy both of its New York City locations through May 11. "Junction" refers to the 31-year-old artist's personal history of living at geographic and emotional crossroads. Smith spent his first nine years in Jamaica, moved to Miami with his family for another nine years and then spent four more attending the Kansas City Art Institute in Missouri, where he trained in ceramics.

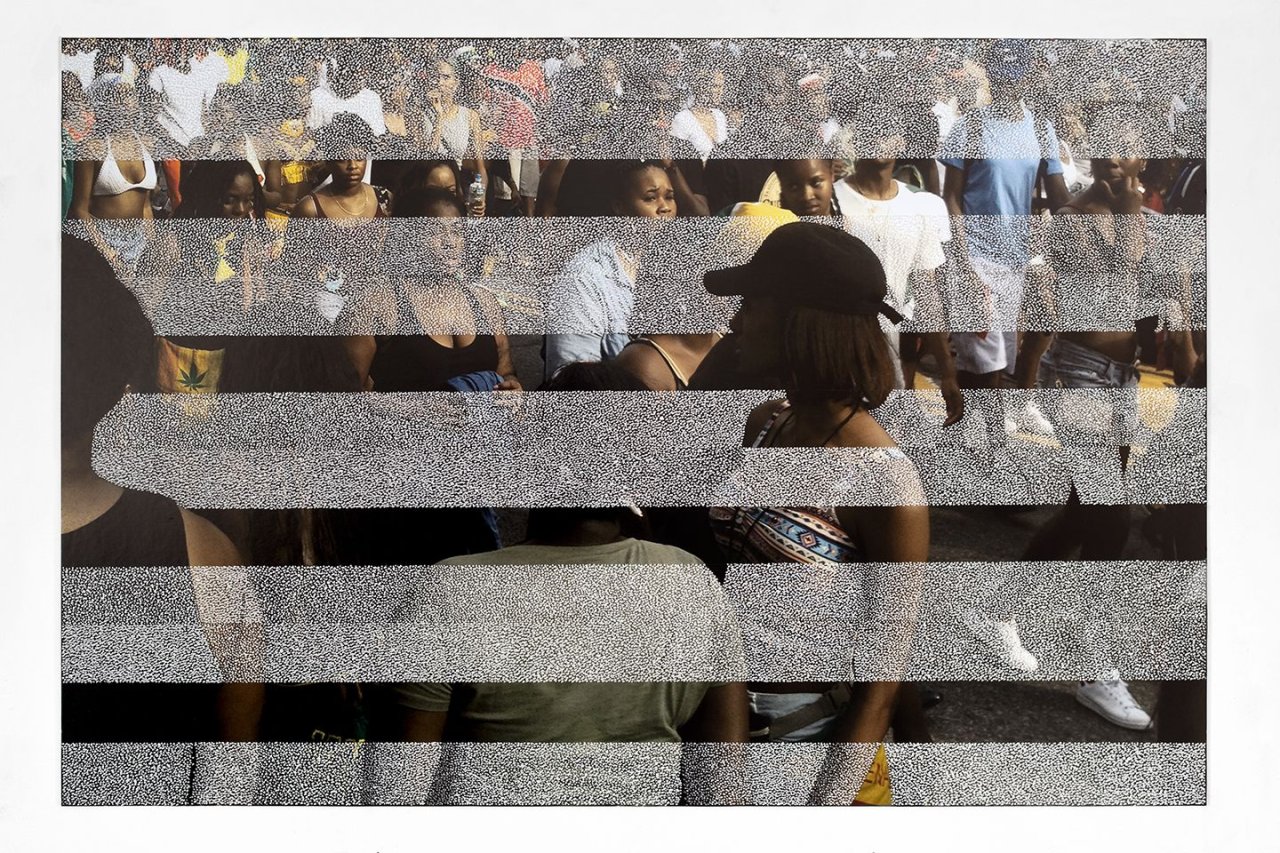

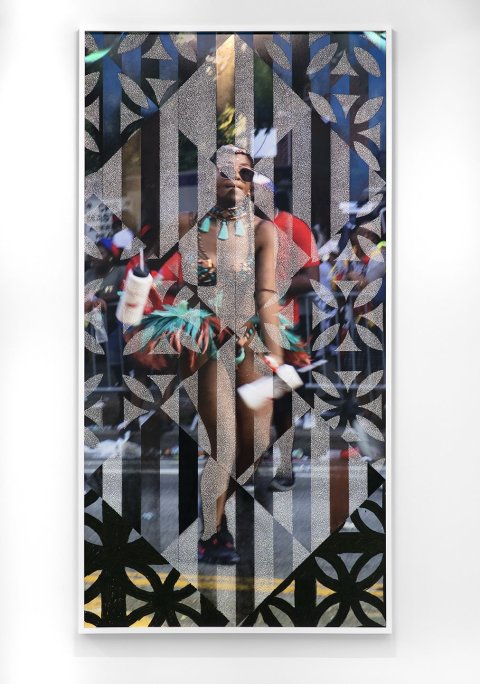

"Junction" is photo- based and features what Smith calls "picotage," a process he began experimenting with in 2012. Inkjet pigment prints—one photograph or several combined—are layered onto white museum board; using a sharp ceramics tool, he exposes the white board underneath, picking out a pattern based on the cut-out cinder block walls and breezeways popular in Caribbean architecture in the '50s and '60s—a significant time in the islands, when hundreds of thousands immigrated to the United States and Britain. The patterns add a metaphorical layer to the photos, speaking to the larger experience of the African diaspora, "of understanding what it means to leave a land," says Smith, "of how you are invited into a place and then forbidden to participate.

The scenes in the images—the beaches of Jamaica, friends and family hanging out, and extravagantly costumed dancers at West Indian festivals in Brooklyn—are seductive precisely because they are partially obscured, the picked-out sections reminiscent of the lace veils that offer tantalizing glimpses of a subject while also protecting it from the eyes of the viewer. "This is what we're doing," says Smith, "but you're not welcome." One image of a beach is topped with spray-painted strands of beads, like those used for curtains in Jamaica. "You know the Iron Curtain?" he asks. "I think of this as the Caribbean Curtain."

Smith has an archive of thousands of images, each capturing a fleeting moment "of an amazing day in my life," he says. "A lot of them are about celebration, about dance and rhythm, the vibrancy I was feeling." Some are intentionally blurred—a way, he says, "of showing loss of memory and history, of things not being clear. You know, Jamaica's motto is 'Out of many, one people.' Syrians, Germans, Jews, Indians, Chinese—they all migrated to the island. But no one thinks of Jamaica as a land of many. A lot of history, everywhere, is destroyed or suppressed."

As an outsider, wouldn't he be more interested in eliminating walls and boundaries? He shakes his head. "I like them. I'm fine with being included, and I'm fine with being excluded—I'm all about my personal space."

Smith is never happier than when shut up in his bright white Brooklyn studio, his "sanctuary," where he keeps, among other things, his second-grade sketchbooks. "I always knew I wanted to be an artist," he says, though he admits that, for a while, he entertained two other career options: "No. 2 was cooking—I love food! No. 3 was UFC fighter."

He decided to focus on art. Attending the Kansas City Art Institute and living in the American Midwest was "a great experience"—apart from the brutal winters: "That really got to me." He missed, always misses, the beaches of Jamaica. "It's the one place, other than my studio, that I feel most comfortable," he says. "One of the pieces of art that inspired me the most—I saw it in high school—was Early Sunday Morning by Edward Hopper. There isn't one person in the painting. It's so calm—it reminds me of the ocean."

Smith stops to observe the assistants maneuvering another large piece toward the wall. He inhales shakily, like a parent watching a child take the first steps. The gallery framer walks by and asks if he has had a chance to catch up on sleep. "When I die," Smith replies with a big smile.

There are six hours before tonight's opening party, and he's itching to pick away at the bottom of an image that is already framed. The piece, called Slightly Pivoted to the Sun's Rhythm, features a parade dancer in a bikini top and feathered tutu. How will he know when it's finished? "It's the same as eating—I feel full," says Smith, clearly still hungry. "I want this one to be poppin'!"